Visitors and locals alike may even know the history of the area’s lumber and pulpwood industry. Beginning in the late 19th century, commercial logging interests moved into the region and began cutting stands of ancient timber for use in construction, shipbuilding, tanning and paper manufacturing. Within a few short decades, much of this area was clear cut, leaving only the most remote and inaccessible old-growth forests untouched, while other areas were filled with slash and other logging detritus.

If you think hiking in rugged landscape can be hard, just imagine the difficulty involved in extracting logged timber from an area as rugged as the elevations around Elkmont, where the Little River Lumber Company worked in the early 20th century.

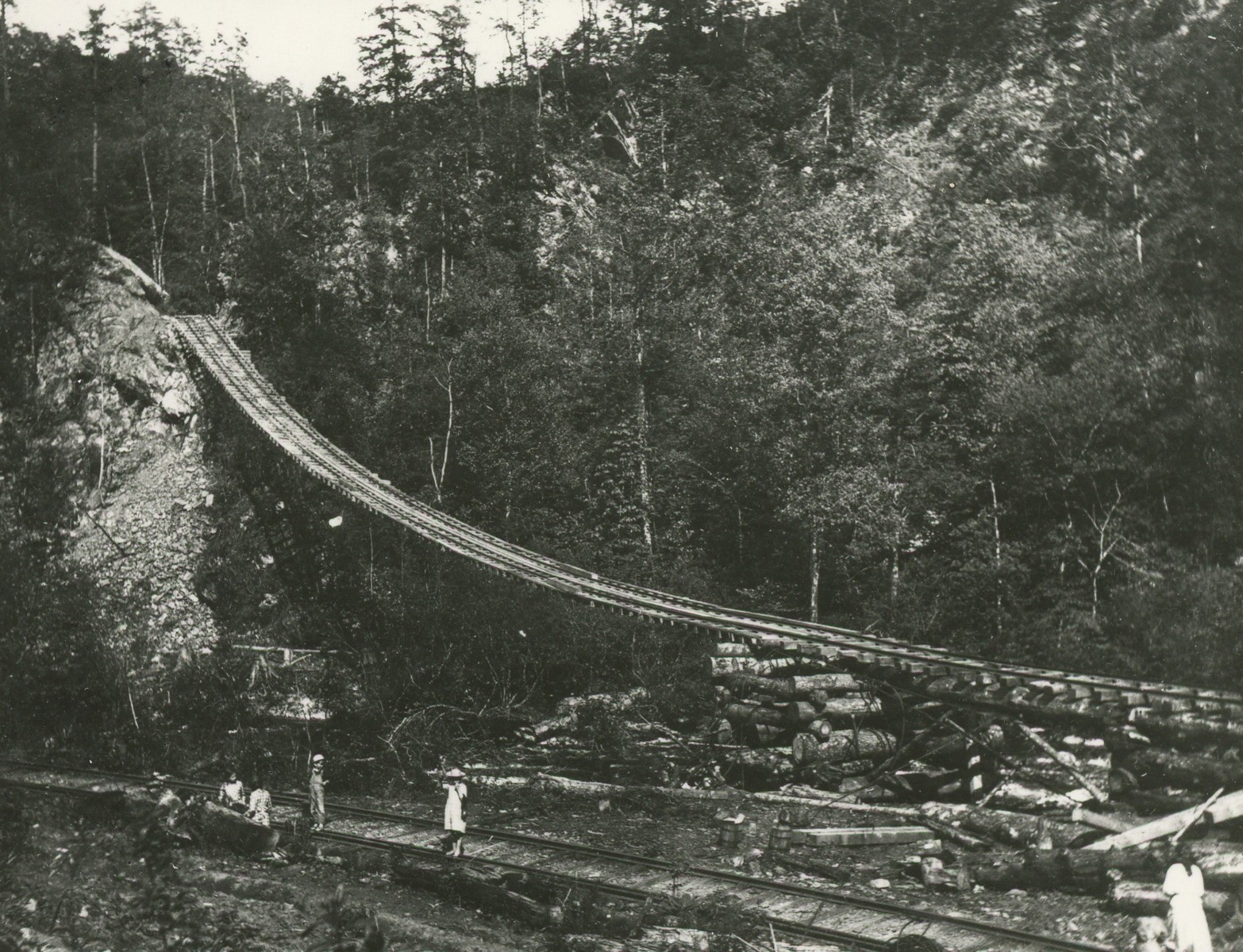

Steep terrain and natural features like waterfalls made access to the Meigs Creek drainage and the unlogged timber it protected difficult to say the least. But with the increasing likelihood of the establishment of a national park in the Smokies, and with other areas yielding fewer logs of sufficient size, it became more and more necessary for the lumber company to access isolated timber stands. The problem was gaining access to such isolated terrain. A traditional railroad grade couldn’t reach this craggy area, and other logging techniques were impractical. The solution to accessing this pristine timberland was the construction of a massive swinging bridge.

Built about 1920 and spanning the Little River at the mouth of Meigs Creek, the bridge was constructed of steel cables and large logs joined with traditional crossties and steel rails. Guy cables were installed to prevent the bridge from swaying side to side, and no trestles were used to support the span. The bridge wasn’t designed for use by a standard locomotive and was never traversed by one. Instead, a steam-powered logging machine called an incline engine was used in the steep terrain. Traveling on track laid up an incline, a cable was splayed out from the front of the incline engine. The cable was then secured to a large tree or stump, and the engine used its own power to haul itself up the track to untouched timber.

Surry Parker of Pinetown, N.C., built the incline engine that operated across the swinging bridge. But getting the “Sary Parker,” as the operators for the Little River Lumber Company called it, up the swinging bridge wasn’t straightforward. The length of the bridge prevented the engine from winching itself up the incline. Instead of a traditional steam locomotive, Baldwin engine #148, used a block and tackle secured on the south side of the river to slowly draw in the Sary Parker to the top of the swinging bridge.

Once operating in the Meigs Creek watershed, the Sary Parker went to work, using a boom crane to lift cut logs onto a special shortened flat car. When full, the flat cars were lowered down the bridge by a cable from the incline engine. On the other side of the Little River, the cars were unloaded and hauled up the bridge by the Surry Parker engine. Surprisingly, in an era when logging and railroad accidents were commonplace, there were apparently no serious accidents while the swinging bridge was in operation.

Though the Little River Lumber Company sold its holdings in the Great Smoky Mountains to the State of Tennessee in 1927, they continued to log these mountains until 1939, when they ceased operations and dismantled their infrastructure, including the swinging bridge. Few scars remain of the activities of the lumber companies in the Great Smoky Mountains, but if you know where to look, you can certainly see their imprint.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.