When I started working at Great Smoky Mountains Association in 2017, I figured I would write a book at some point in my tenure. But I never dreamed I would become the author of a children’s book.

The impetus for it goes back to my own childhood, which was idyllic. I grew up in Eastern Kentucky at a summer camp for which my parents acted as overseers. I spent summer days swimming, canoeing, hiking, and horseback riding, immersing myself in a landscape of Appalachian wildlife. The only sadness I recall was seeing animals hit and killed on roads.

The impetus for it goes back to my own childhood, which was idyllic. I grew up in Eastern Kentucky at a summer camp for which my parents acted as overseers. I spent summer days swimming, canoeing, hiking, and horseback riding, immersing myself in a landscape of Appalachian wildlife. The only sadness I recall was seeing animals hit and killed on roads.

In my 30s and 40s, I traveled the world as a tourism professional, and lived for a period of time in both Canada and Costa Rica. These experiences raised my awareness of wildlife road mortality as a global problem.

Not long after I began working in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I got involved with a group of federal, state, Tribal, and non-governmental organizations discussing the need for wildlife-crossing structures along Interstate 40 near the park boundary—in the Pigeon River Gorge between Asheville and Knoxville. I was drawn to this group because I had been seeing black bear, white-tailed deer, and even an elk killed on Interstate 26 north of Asheville, near my home.

Flash forward to late March of 2020. The pandemic ground most of my travel and social interaction to a halt. But sitting out by the creek on my six-acre property in Flag Pond, Tennessee, a colleague in the wildlife-crossing collaborative popped a startling question: “When are you going to write a children’s book about the need for wildlife crossings?”

I must have spewed a five-minute litany of protests. At the apex of my career as a creative director managing five leading-edge innovators, being involved in a plethora of engaging projects in the park—how could I begin to think about taking on such a project?

The next day, I found myself at the creek again with a yellow legal pad and a pen. I filled six and a half pages with a story draft, and about six more with detailed notes. I created an outline for eight chapters, drew a crude map, and charted out personality types for 16 characters of various species. This was just the beginning: For the next six weekends, I typed on my computer, finishing the narrative in early May.

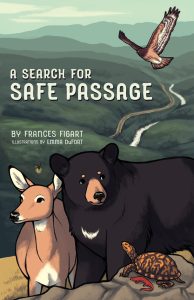

A Search for Safe Passage tells the story of best friends Bear and Deer who grew up together on the North side of a beautiful Appalachian gorge. In the time of their grandparents, animals could travel freely on either side of a fast-flowing river, but now the dangerous Human Highway divides their home range into the North and South sides.

tells the story of best friends Bear and Deer who grew up together on the North side of a beautiful Appalachian gorge. In the time of their grandparents, animals could travel freely on either side of a fast-flowing river, but now the dangerous Human Highway divides their home range into the North and South sides.

Many animals have died on the Human Highway trying to follow the ancient trails. So, to keep everyone safe, Turtle, the elder, has created a law forbidding anyone to try to cross, and a Forest Council has been formed to look for solutions. Hawk and Owl scout the area each day for other ways to travel from North to South, with no luck. But on the night of a full moon, two strangers arrive from the South with news that will lead to tough decisions, a life-changing adventure, and new friends joining in a search for safe passage.

The story is fiction, but it is based on the real-life problem. The setting is a microcosm of the Pigeon River Gorge, a beautiful, wild landscape with a treacherous highway bisecting ancient wildlife corridors. In the back of the book is an interpretive section about the real-life animals and their actual wildlife crossing needs. It is geared for ages 7-13 and contains allusions and wit for adults to enjoy with kids.

All the while I was preparing the book for publication, I was supporting the collaborative effort to collect data, plan, and help implement wildlife crossings along the dangerous 28-mile stretch of highway in western North Carolina and east Tennessee. On February 25, the public became aware of Safe Passage: The I-40 Pigeon River Gorge Wildlife Crossing Project. Six partners—The Conservation Fund, Defenders of Wildlife, Great Smoky Mountains Association, National Parks Conservation Association, North Carolina Wildlife Federation, and Wildlands Network—have made it possible for donations to be collected for future road mitigation and wildlife crossing structures via a fund at SmokiesSafePassage.org.

All the while I was preparing the book for publication, I was supporting the collaborative effort to collect data, plan, and help implement wildlife crossings along the dangerous 28-mile stretch of highway in western North Carolina and east Tennessee. On February 25, the public became aware of Safe Passage: The I-40 Pigeon River Gorge Wildlife Crossing Project. Six partners—The Conservation Fund, Defenders of Wildlife, Great Smoky Mountains Association, National Parks Conservation Association, North Carolina Wildlife Federation, and Wildlands Network—have made it possible for donations to be collected for future road mitigation and wildlife crossing structures via a fund at SmokiesSafePassage.org.

Through all this work, I have come to the realization that humans must refuse to accept roadkill as a natural part of traveling in our modern world. There are viable and affordable solutions that have succeeded all over the planet—and the time has come to do something about this issue in our biologically diverse Southern Appalachian landscape.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.