In the not-too-distant past, moonshiners were common in the Smoky Mountains and throughout the Southern Appalachians. They were mountaineers who made part of their living manufacturing spirits by moonlight in the hidden coves and caves in order to evade taxes levied by the United States government.

In 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed into law a tax on distilled spirits in order to raise money to fund the Civil War. The tax was substantial. It started at 20 cents/gallon when the law was first passed then rose to $2.00/gallon in 1865. The alcohol tax varied over the subsequent years. It was $1.10/gallon starting in 1894 until the passage of the 18th amendment in 1920 outlawing the production and selling of alcoholic beverages otherwise known as Prohibition.

According to Dan Pierce in Corn From a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains (Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2013), alcohol production was common throughout the American colonies and in the early republic. Many mountaineers were of Scots-Irish heritage and had a long family history of making distilled spirits.

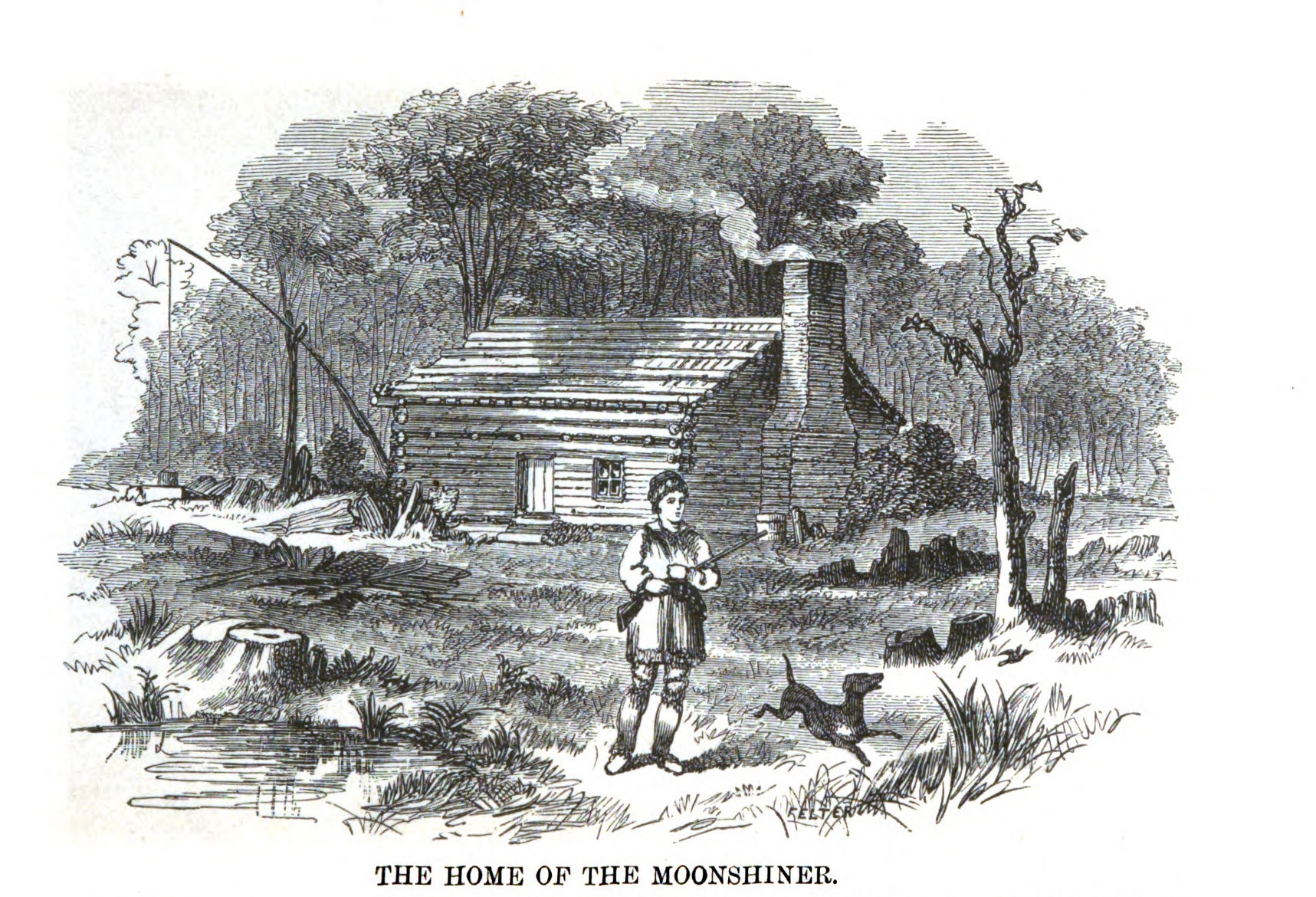

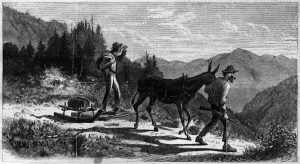

These settlers in the Smokies often arrived carrying a copper pot distillery. Of course, it was that very prevalence of distilled spirits production that made it potentially a good source of revenue for the federal government. But many mountain people could not afford to pay such a high tax and resented a levy on a product that previously had been tax-free. They responded to the tax by making and selling moonshine, an illegal version of the whiskey that their families had made for generations.

For the government, moonshining was a matter of lost revenue; for the Smoky mountaineer, it was a matter of simple economics. Corn was the main staple crop in the mountain region because it was cheap, sufficiently hardy to be grown on steep terrain, and could be easily ground in a crude tub mill.

The expense of storing and transporting a bulk agriculture commodity out of the mountains was greatly outweighed by the revenue that could be generated by reducing the corn into a fermented liquid and sealing it in a jar, thus increasing the monetary value of the corn as well as making it considerably easier to transport. The income from the sale of moonshine, often the only cash income for mountaineers, could be accumulated to meet local property tax obligations which, unlike the whiskey tax, the mountaineers had no objection to paying.

One of the best 19th-century accounts of illegal whisky production in the Southern Appalachians was After the Moonshiners By One of the Raiders: A Book of Thrilling, Yet Truthful Narratives, published in 1881. The author, George Wesley Atkinson, was a revenue agent, a public official hired by the federal government to track down and arrest individuals who made illegal spirits.

After his short career as a federal agent, Atkinson went into politics, later becoming governor of West Virginia. While he offered little defense for the activity of illegal whiskey production, he pointed out that wages in the Smoky backwoods were low. A good farmhand could be hired for 50 cents a day. If a moonshiner could produce just one gallon of his “mountain dew” each evening, he could employ a farm hand to do his hard work while he could spend his days hunting and fishing. All the stills that Atkinson destroyed could easily produce more than one gallon per day making moonshine a profitable business, assuming the moonshiners could avoid the federal agents charged with shutting down their stills.

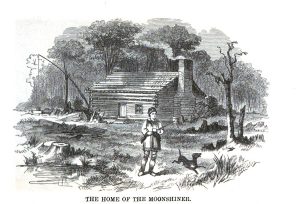

Once the moonshine was made, it had to be marketed in such a manner as to avoid detection by revenue agents and their local informants. Many gallons were sold or bartered to neighbors. Others were carefully concealed in wagons, hidden under quilts and other goods, and taken to markets to be sold surreptitiously.

Moonshiners always ran the risk of detection at any point in the process. Some ended up in front of a judge and served time in jail only to be released and go straight back to making moonshine, hoping that the still had not been destroyed as part of their arrest.

Next time: More on the process of making moonshine.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.