Longtime readers of Smokies Life will recognize the name David Brill like that of an old friend. Starting with the first issue in 2007, Brill has published upwards of 20 stories in the magazine’s pages—everything from an inquiry into the letters of unofficial park historian Hiram Wilburn, to fly fishing in Cades Cove, to traversing the Mountains-to-Sea Trail by moonlight.

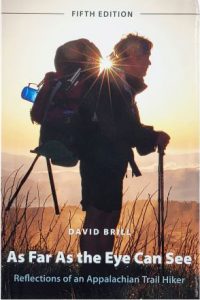

But his career as a chronicler of America’s public lands stretches back much further than that. In 1979, at the age of 23, Brill hiked the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine, an experience detailed in his first book, the essay collection As Far as the Eye Can See, published in 1990. Now in its fifth edition, eighth printing (University of Tennessee Press, 2020), the book has since become a classic of AT literature; Brill’s anecdotes and lessons learned remain as useful as they are inspiring to generations of actual as well as would-be thru-hikers.

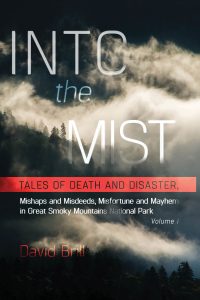

Several decades into his writing career, Brill continues to produce enlightening work about humanity’s relationship with nature from his cabin near Obed Wild and Scenic River on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. In 2017, Great Smoky Mountains Association published Into the Mist vol. 1, a compendium of disasters and fatalities that have occurred in Great Smoky Mountains National Park since 1931. Despite the book’s morbid subject, Brill’s dramatic renderings of 13 true stories are at once compassionate and thrilling. A valuable record of the awesome and often deadly natural forces that shape the Smokies, the title also serves as an educational safety manual to help future park visitors avoid potentially dangerous situations.

I recently sat down with David at the Lilly Pad Hopyard Brewery near Obed to discuss his origins and influences, how he built a lifelong career as a nature writer, and what continues to fascinate him about America’s most-visited national park.

Smokies LIVE: How did you get started writing? Who were your influences?

David Brill: When I was an undergraduate at Indiana University, I studied modern American literature—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck. My pipe dream was to be a novelist. But I dismissed that as being impossible; that was never going to happen.

SL: Why did you think it was impossible?

DB: I didn’t think my work measured up to that of my heroes. But I’d been planning to hike the Appalachian Trail, so in 1979 I set out. As Thoreau puts it, “Only that day dawns to which we are awake.” I totally woke up. I had an epiphany in Hot Springs, North Carolina. I devoted a whole chapter to that in As Far as the Eye Can See. It’s like, there are no rules. You can live anywhere, anyhow you want. And that was a real pivot for me.

Every day was this wild awakening. New territory, new terrain, new people. So when I reached the end of the trail, I knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to be, not a fiction writer, but a journalist, because I had this story in me I was burning to tell. In the context of a lifetime, five and a half months is not that long, but it completely transformed me.

SL: There’s a moment in the Hot Springs passage where you notice an older man singing a song about “winding up where you ought to be.” It reminded me of your more recent essay about building a home near Obed Wild and Scenic River. I was wondering if you could speak about how these places inform your more personal writing, and if you think your story might affect how your readers experience these natural areas. Do you consider that?

DB: Well, I’ve always trusted my reader to give me a fair break if I’m totally open and honest. And the experience I had in Hot Springs was profoundly affecting for me. I think, over the years, hundreds of people have had similar experiences in that secular-yet-sacred space.

I think, to be sort of aseptic about it, to experience something that’s affecting you emotionally and not make that part of your story—it’s going to deprive the reader of the real meat of what that experience is. I mean, we don’t go to national parks strictly to identify plant and animal species. We enter the parks because we seek a visceral experience of being there in that wild environment.

SL: What was it like to take your AT experience and shape it into your first book?

DB: As Far as the Eye Can See started as a failed magazine assignment, in 1989. For ten years I carried that experience around with me through different editing and writing jobs. It wasn’t until a magazine called Tennessee Illustrated wanted me to go out and hike seven days in the Smokies along the Appalachian Trail that I found a way to shoehorn it in. A photographer and I went out, and we hiked. And when I sat down and started writing that essay, the larger story just tumbled out of me. I got to 20 pages, and I realized I had quadrupled the assignment. It was a cathartic outpouring of all these memories. But it was cogent, it was organized.

I submitted it, and the editor called me the next day and said, “I have some good news and some bad news.” The bad news: “This is all over the place. It’s about the whole Appalachian Trail. I’m gonna have to kill this story or you’re gonna have to rewrite it.” So I asked, “What’s the good news?” He said, “You have a book in you.” Soon after, he proffered an introduction to a regional publisher. Over the next eight months, I crafted As Far as the Eye Can See and shipped it off to Rutledge Hill Press.

SL: Eight months is an impressive turnaround time for a full manuscript. How’d you get it done so fast?

DB: I was on fire with that subject. I was probably at my peak stylistically. Another influence of mine is The Flow Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. It’s about optimal experience, when time seems to disappear. You’re fully immersed in something. That’s what I aim for in my writing process. I can’t always quickly find the portal into the flow space, but once I’m in there, no matter what I’m working on—it can be eight o’clock in the morning and the next thing I know it’s chilly, the sun’s gone down, and I need to pull on a sweater because I’ve been writing all day.

Working yourself through your ritual, however you start the process—once you get past that rough starting phase and you tumble headlong into whatever it is you’re working on, there is nothing else in the world but that story, that chapter. That to me is a state of bliss. If that happens, you know that what you’re writing is solid.

SL: Do you think your experience thru-hiking the Trail, being fully absorbed in the wild environment for so long, might have given you a taste for “flow experience”?

DB: Yes, absolutely. In the book’s chapter “Learning to Walk, Learning to See,” I describe often becoming deeply immersed in memories and reflections as I moved through the forest. I describe it this way: “And so—lost in thought—I passed the miles, and often, by day’s end, I was jarred from my reverie by the sound of companions ahead in camp. I would then realize that I had traveled six or ten or twelve miles without recalling a single step.”

Coming next month, part two of our interview with David Brill where we will learn more about his evolution as a writer, his work with Smokies Life, and what he’s working on now.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.