As much as I love waterfalls, I’m not so keen on traffic. As the 2022 Steve Kemp writer in residence, one of my personal goals has been to explore as much of the park as possible, which sometimes subjects me to delays given the number of other people with similar goals. Invariably, though, my efforts are typically rewarded.

My dilemma was whether to ask residency namesake Steve Kemp to face those delays with me on a trek to Abrams Falls, the trailhead for which sits about halfway along the 11-mile loop through Cades Cove at the number 10 marker. Given the many historic structures scattered across the once-thriving rural Appalachian community, Cades Cove is a notorious traffic hot spot. While numerous signs advise people to keep moving or pull off in the multitude of designated pull-off spots, too many see those signs as little more than a suggestion, bringing traffic along the one-way thoroughfare to a standstill.

The ever-affable Steve was happy to join me. When we entered the loop shortly after 8:30 a.m., traffic was already backed up. Just as Steve asked if we should choose another trail, we saw the reason for the holdup. Volunteers from Friends of the Smokies, a nonprofit organization that raises funds and awareness for GSMNP, were letting visitors know there were artists in Cades Cove as part of their inaugural week-long Plein Air in the Smokies event. They told us we would most likely see a few painters at work and that the work would be available for sale to benefit the park.

After listening to their explanation, we heaved a sigh of relief and drove on, albeit in a fits-and-starts sort of way. As eager as I was to reach the trailhead, the slowdowns helped me pay closer attention to the landscape. What blew me away was how this last week of September had painted the landscape in vibrant goldenrod yellow. Steve said he believed Cades Cove was at its most glorious when the goldenrod bloomed. I tucked that thought away as we drove on.

One of the things I like best about Steve is his skill in appreciative lingering. After casually meandering to the falls, he scoured its wide surrounding pool, looking for the ideal snack spot. I happily followed as he crossed various rocks until he found just the right boulders from which to eat and gaze at the lush waterfall cascading before us.

As we quietly and contentedly nourished bellies and spirit, I overheard two women nearby, clearly excited about something they’d just seen. When I asked, they pointed to a fuzzy head breaking the water’s surface in the distance—a river otter!

One cute, fuzzy head sighting led to another. Steve counted seven or eight if I recall correctly. We felt fortunate to watch them play for a few minutes before they swam to shore. From there, they slid lithely over and under rocks until, bloop, they disappeared into what we imagined must be their den beneath a large boulder.

I love those moments when adult sensibilities transform into childlike glee. The joyful look on Steve’s face was priceless. A 30-year GSMA veteran, he also had insider information, remembering when the park reintroduced the northern river otters in the mid-eighties. It wasn’t until our hike, though, that he got to see them thriving in the wild, most likely because they tend to be nocturnal creatures. Like Steve, I was also grinning from ear to ear at our good fortune. I don’t know why, but there’s something about river otters that can coax the giddy from the most mature adult.

Happily exhausted by the time we reached my car, I was eager to head to my residency apartment for a hot shower. A little voice in my head, though, reminded me of our not-close-enough encounter with the goldenrod. As exhausted as I was, I knew, to avoid any nagging regrets, I had to drive back to Cades Cove.

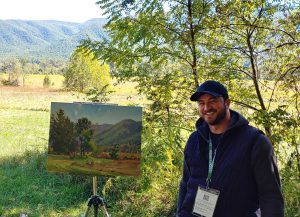

Once again, the volunteers approached my car to share information about the plein air painters. Since there were no longer any time constraints, I pulled over to chat with one of the plein air artists—Dan Mondloch from Cold Spring, Minnesota. Not only was it Dan’s first time in the Smokies; it was also his first time in any national park. “What stood out to me,” he said, “was that it seemed like every ten minutes, the light would pierce through a different hole in the canopy and provide a new arrangement of shadow patterns and illuminate a different part of the landscape.”

He said he heard from fellow artists it seemed like a spiritual experience, something I completely understood from my own adventures. I was eager to experience the goldenrod’s “illumination” for myself. A member of the aster family, goldenrod thrives in open fields like those that comprise so much of the Cades Cove loop.

While it’s lovely to admire flowers from a passing glance, nothing beats standing among and becoming one with them. I could feel myself sway as the tall blossoms waved in harmony with the breeze. I knew why painters like Dan chose to create in Cades Cove. It was like standing in a richly painted canvas, a broad swath of yellow beneath a deep blue sky, all set against the lush mountainscape.

Just when I thought a moment couldn’t be any more beautiful, a monarch flitted by. My eyes shifted from macro to micro as I scanned the flower clusters, looking for more, trying to photograph them in their rare resting moments.

Thirty minutes or so later, I was ready to rejoin the vehicle conga line. While I was still not keen on traffic, stepping away from the fray and into a flow of my own made putting up with the slow pace little more than a minor inconvenience.

Sue Wasserman is the author of A Moment’s Notice and Walk with Me: Exploring Nature’s Wisdom. She has also written for the New York Times and Southern Living. She currently lives in North Carolina.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.