When a wallet talks, Mike Aday listens. At least metaphorically speaking.

In fact, coaxing such a curious conversation is part of Aday’s job as the archivist for Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Part of my role as the 2022 Steve Kemp Writer in Residence is to learn more about how he brings history to life in addition to breathing new life into history.

As has so often been the case throughout my residency, I had no idea there was such a place as the Collections Preservation Center. The six-year-old, climate-controlled, 14,000-square-foot building in Townsend, Tennessee, is home to an impressive 1.4 million records, ranging from maps and photographs (35,000 of them) to Cherokee pottery shards and Appalachian farm tools, and so much in between. The collection under Aday’s purview has items dating back to 1780.

“The human history you find in archival holdings is fascinating,” he says. “It’s amazing all the life that happens outside of the public eye.”

Aday is the impassioned gatekeeper, collecting, protecting, and sharing the wealth of information, all of which ties back to the national park. The compilation of genealogical information alone is impressive, which is understandable given the fact that the park is comprised of 1,600 separate tracts of land.

“Someone sees their name on a tombstone and wonders if they’re related,” he says. “The question gets back to me to try and answer.”

For Aday, business as usual often involves working with academics digging into various aspects of Southern Appalachian history. You can often find him sharing the collections through his community outreach efforts, helping people understand the park and its history better. He even makes time, and gladly so, to answer questions from ten-year-olds regarding how the Smoky Mountains got their name.

While it’s uncommon these days for Aday to get new donations to the collections, it still happens. The aforementioned wallet was just such a donation. It was delivered into the park’s hands by the great-great-granddaughter of Cades Cove resident Elijah Oliver.

“Oliver was born in 1824, the son of the first White European family to settle in Cades Cove,” Aday offers. “He became a prominent figure in the community.”

According to Aday, Oliver’s wallet looked more like a leather pocketbook than a traditional man’s wallet and was crammed full of folded bits of paper.

“Like George Costanza from Seinfeld, whose notoriously overstuffed wallet was the fodder for many jokes,” Aday says, “it was pretty clear Elijah had been accumulating these bits and pieces for decades.”

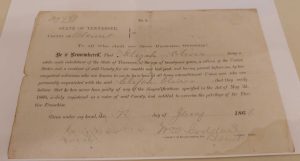

Decades indeed. The oldest piece dated back to 1840 while the most recent was from 1910. Exhilarated by the donation, Aday recounted how he went to work trying to preserve each of the dated documents. The process, he explained, required careful extraction of each item before he could, with equal care, unfold them.

“Each piece had to be meticulously cleaned,” he remembers. “As you can imagine, after all those years, they were filthy. I used special brushes to try and remove the dust.”

Certain he had to humidify the papers to flatten them but unsure how to achieve that, Aday did some online research. The resulting “state-of-the-art” humidifying system was crafted from a white plastic storage container, plastic coated wire rack, and a piece of unbleached muslin paper. Oh, how I wish I could have watched this master at work. I’m not sure I’ve ever used the word “fastidious” before in an article, but I imagine that word clearly applied to Aday’s restoration and preservation efforts.

“I wetted down the muslin, placed the rack on top of it, put the paper on top of the rack, and placed the lid on the container. I checked on it every 15 minutes to see if the fibers had loosened. Then I sandwiched the flattened paper between pieces of blotter paper until it was completely dried. The process took about three weeks during which time I put other projects on hold. When the first batch was completely finished, I texted my wife and told her, ‘Oh my God, it worked!’”

Cades Cove community members, according to Aday, supported the abolitionist movement. As a result, the community often served as a temporary safe haven for Union soldiers who had escaped from Confederate prisons. A dedicated advocate of education, Oliver even saved correspondence to the school board authorizing teacher pay.

Such correspondence is not an uncommon find in Aday’s world. In fact, he has selected 20 historic letters that he’s researched and written essays about for a forthcoming book, Letters from the Smokies, to be published by Great Smoky Mountains Association in 2023.

“Some of the topics were difficult to write about, particularly those concerning the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the African American history in the park,” he says. “These stories have been under-explored in the past but are crucial to our understanding of the park and its history.”

Knowing the painstaking efforts Aday goes through to bring history and historic voices to life, I have no doubt it will be a book well worth reading.

Sue Wasserman was the 2022 Steve Kemp Writer-in-Residence and is the author of A Moment’s Notice and Walk with Me: Exploring Nature’s Wisdom. She has also written for the New York Times and Southern Living. She lives in Bakersville, North Carolina.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.