With some variations, all moonshiners used common techniques for making illegal whiskey. The process, bolstered by a few secret tricks of the trade, was passed down through the generations.

Former revenue agent John Wesley Atkinson in After the Moonshiners By One of the Raiders: A Book of Thrilling, Yet Truthful Narratives provided extensive details on moonshine production along with accounts of his escapades. According to Atkinson, the “first requisite for an illicit still was a good stream of cool water.” A spring was “preferable because its temperature does not rise in hot weather, and it is positively necessary to have cold water to produce whiskey.”

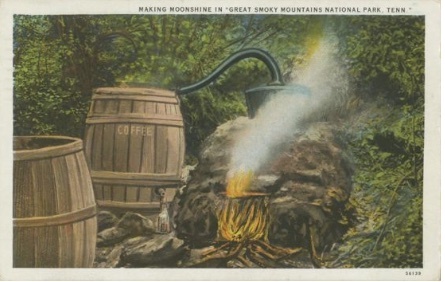

The second requisite was seclusion. The Smokies afforded the mountaineers countless hollows isolated in deep inaccessible reaches, hidden by thickets of rhododendron on all sides with a cold spring and plenty of firewood nearby. Furthermore, because the surrounding hills were so high, smoke from the fire used in heating the mash—the fermented grain that forms the basis for the final product—was dissipated into the atmosphere before it rose above the summits of the mountains, often making it difficult for the revenuers to locate a still from the smoke trail.

But first the moonshiner must make the mash. Good water for fermenting the grain was an essential ingredient. According to historian Dan Pierce in Corn from a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains (Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2013), “‘Soft’ water that contains few trace minerals is generally regarded as best for making good whiskey.” Soft water creeks were common in the Smokies with Cades Cove being a prime location. The locals learned to judge the softness of the water from the surrounding vegetation.

Moonshine, like any other sour-mash whiskey, was made by soaking the grain, usually corn, in water until sprouts appeared. As outlined by Pierce, once the corn had sprouted and been allowed to dry, it was then ground in a mill. The ground meal was then mixed with water and malt and allowed to sit and ferment for several days until the mash became foamy. Once the foam disappeared the mash was ready for the still.

Although some still houses were proper cabins, the romantic image of the lone Smoky mountaineer huddled under a hastily assembled pole lean-to hidden in some inaccessible ravine and tending to his crude hand-made still was a fairly accurate depiction of the moonshiner and his craft. Atkinson wrote that a proper still was made of copper and shaped like a tea kettle. The average capacity of a still was about 125 gallons. Copper was the metal of choice, according to Pierce, because “it is strong, tough, conducts heat well and evenly, does not leach metals into the alcohol, and does not corrode.”

A fire was built around the still causing the mash to heat and produce a vapor. A copper or tin “worm,” a coiled hollow tube, was attached to the still and then placed in the spring water. The cold water caused the vapor to condense, forming a liquid. The most skilled moonshiners, who did not use a thermometer and heated the still with kindling, became adept at keeping the heat above 176 degrees, the temperature at which the alcohol evaporated and entered the worm, but below 212 degrees, the temperature at which the water in the mash would evaporate.

The first liquid, called singlings, was low in alcohol and contained impurities. It was filtered and the entire process was repeated a second time, called doubling, to produce the high-alcohol whiskey or moonshine. Atkinson wrote,” Doubling day at a moonshine distillery is almost as important an event to a mountain community as the coming of the circus.” During good weather, a moonshiner could make two to three doublings in a week with the still running day and night in the weeks before Christmas.

It is not known how many mountaineers made moonshine, but some became legends. More on that next time.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.