The scene is a simple one. A young boy, fascinated by slick stones in a creek, picks one up and skims it across the water, trying to reach the other bank.

As wholesome as this scene may appear, it is one that shouldn’t happen in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

As wholesome as this scene may appear, it is one that shouldn’t happen in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

For the protection of Smokies wildlife and other natural resources—including plants and trees—park officials stress that nothing should be removed from the park and items like stream rocks should not be disturbed.

It’s all a part of the park’s efforts to keep the mountains, valleys, and streams of the Smokies a special place for hundreds of years to come. In addition to battling litter—called an increasing issue by park officials—visitors must protect wildflowers, plants, trees, animals, and yes, even rocks, by leaving them as they are.

“I see people gathering up stream rocks as if they might put them in an aquarium,” said park ranger Julianne Geleynse, who works in resource management. “They think, ‘Well, there’s plenty of rocks. What’s wrong with taking a few?’ But think about that. There are more than 10 million people visiting this park every year. What if every one of them starts taking something? Then you’d see an impact, and you’d see a change in this beautiful place you’ve come to enjoy.”

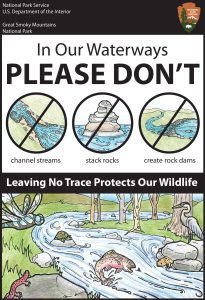

It’s important not to disturb stream rocks because salamanders and fish nest beneath them, Geleynse said. Adventurous children sometimes stack stones in creeks or try to create a small dam with them. It’s a seemingly innocent exercise, but it can create issues for the animals that live in the stream.

“I like to use an analogy that people understand,” Geleynse said. “When you move rocks, it’s similar to going up to a bird’s nest with eggs, tearing it apart, and throwing it to the ground. Most people don’t understand there are eggs and nests of amphibians under these rocks.”Park entomologist Becky Nichols said insects and salamanders inhabit different sections of streams. Some prefer fast-moving water; others live in deeper pools.

“Hellbenders require certain-size rocks for setting up their nests,” she said. “The male hellbender has a territory. They’re typically around and under large rocks, and if someone starts moving the rocks around—for tubing, for example—the male might have to move to another location. And there’s probably another male there, so they fight over the territory. These are unintended consequences that most people don’t know or think about.”

In her travels in the park, Geleynse said she tries to educate visitors, especially children, about proper use of streams. “If we see an area where people have built a dam or stacked rocks, we’ll break it down and put it back to a natural look,” she said. “We often have children to help us break down the dams. Then they will do it later on their own.”

Geleynse said sometimes these stream habits are cultural. “People will say that they’ve been building creek dams since they were kids. Those people I really try to talk to in the field. Having an in-person conversation is far more effective, and if I can show someone the wildlife we’re protecting, it makes a much bigger connection.”

Other visitors are tempted to cut or dig up the vibrant wildflowers that decorate many trails in the Smokies. “Some people don’t necessarily have ill intent,” Geleynse said. “They don’t understand it’s a bad thing. They think it’s pretty, and they want it for their yard. But it’s always best to think about leaving things the way you find them.”

A few notable (and delicious) exceptions to the leave-it-be rule in the Smokies include fruits, berries, nuts, and certain mushrooms.* Park visitors are actually free to mindfully harvest these wild Smokies foods for personal use within limits, which helps to ensure collection doesn’t adversely impact plant life or wildlife food sources.

A full description of the park’s harvesting rules can be found here, but for now, hungry hikers can rest assured that picking and savoring delicious blackberries and blueberries along the trail is one scene that remains welcome in the Smokies.

* No wild mushroom should be eaten unless its identification is absolutely certain, which usually requires an expert to determine. Many mushrooms are poisonous, and some are deadly. The responsibility for eating any mushroom or fungus rests with the individual.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.