When I got a text from Elizabeth Ellison on the morning of February 9 that George was in the hospital and struggling, I was actually in the Smokies that he loved — and we were having some very strange weather.

The wind that morning was so fierce I nearly blew away trying to make it from my car to Twin Creeks Science and Education Center for a seminar. As tree limbs crashed into the building’s numerous windows, Jim Renfro, Air Resource Specialist with Great Smoky Mountains National Park, confirmed that what was going on outside was an 80-mile-an-hour wind.

Looking from the darkening skies and trembling trees to Elizabeth’s text, I thought: George must be fighting hard.

In the days to come, many of us who knew George — and even some who didn’t — would play Van Morrison songs in a symbolic vigil. He especially loved the album Astral Weeks.

The following Wednesday, I got to visit with George at Haywood Regional Medical Center, where Elizabeth told me he got excellent care. I told him that we all knew he had always been a fighter, and it was OK to let go and let others help him at this time. I read him one of his own poems, “Holy Ventures,” which includes these lines:

But should events darken blue skies (as they always will)

We can pass through the gate with the wrought-iron rose

And transcend the realm of burning trees and fallen angels.

By the evening of Sunday, February 19, George was gone.

I didn’t know him for as long as many of you, but we had that tacit yet tangible connection that sometimes can develop between a writer and editor. Much of what I know about him I learned from friends and colleagues such as Janet McCue, with whom he shared the Thomas Wolfe Memorial Literary Award in 2019 for Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography.

When I was editing that book, George told me about the path that led him to his interest in Kephart:

“I have always enjoyed outdoor, travel, and adventure books. In grad school at the University of South Carolina during the late 1960s, I focused on the tradition of descriptive-humorous-sporting literature that flourished in the Southern states in the 19th and early 20th century. Mark Twain took the basic ingredients found in these materials and in 1883 wrote an American classic, Life on the Mississippi. When I discovered Kephart’s two major publications, Camping and Woodcraft and Our Southern Highlanders, carried that genre into the next century, I became increasingly curious about Kephart and started looking into his life and work.”

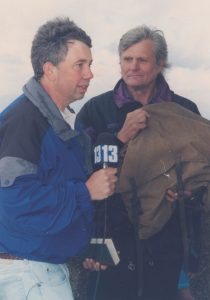

Of course, George would go on to write much of what he called “Kephartiana” and be named Outstanding Journalist in Conservation by Wild South in 2012 and recognized as one of the 100 most influential people in the history of GSMNP in 2016 for his many contributions as a Southern Appalachian naturalist, writer, and teacher.

What follows is an excerpt from a full-length profile that appeared in the spring 2021 issue of Smokies Life written by Janet McCue and Bob Plott, another award-winning author and longtime friend of the Ellisons.

Excerpt from Permanent Camp: George and Elizabeth Ellison create lives of purpose and passion on the edge of the park by Bob Plott and Janet McCue

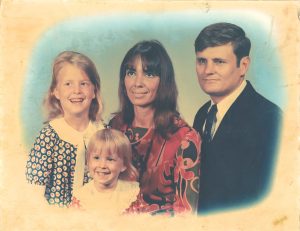

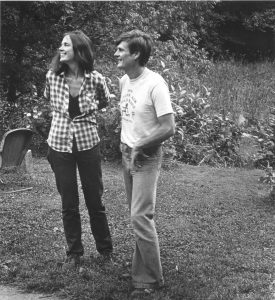

Despite disparate upbringings, George and Elizabeth Ellison seem destined to have been a couple. She a skilled artist, teacher, and Bryson City gallery owner, he a renowned regional naturalist, author, and biographer — this power duo has for decades shared a passion for nature and a dedication to cultivating a sense of place in their chosen home, the Great Smoky Mountains. Named Blue Ridge Naturalists of the Year and collaborating on countless articles and seven award-winning books, they have used their respective arts to connect with the animals, people, and culture of our region in a way that elevates the Smokies time and time again.

On July 4, 1976, George and Elizabeth Ellison moved with their three children into a 45-acre cove on lower Lands Creek surrounded on three sides by Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP). Like most everyone who has experienced the Great Smokies, they were captivated by a setting in which ridge upon ridge fades into the distance in every direction, encompassing an astonishing array of distinct natural areas, plants, and animals. Both have also dedicated themselves to turning artistic and literary passions into meaningful careers rather than letting opportunities to do so slip away.

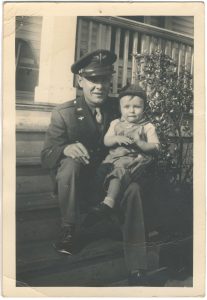

George was born in Danville in 1941, the only child of George Robert Ellison (nicknamed G. R.) and Ruth Ellison. He has no memories of his father, who was assumed to have died along with nine other members of a B-24 Liberator crew that went down over the Madang Province in New Guinea in 1944. G. R.’s supposed death and the specter that he might have somehow survived the crash haunted his son for decades.

“Perhaps it was my way of dealing with the loss or absence of a father,” he said, “but I was intense and tended to shut down and keep things to myself. My focus was on sports, roaming around in the woods, and books. Reading has been a cornerstone in my life . . . I grew up fantasizing about pitching for the Brooklyn Dodgers. I was going to be a pitcher or a sportswriter. The Dodgers never called. But, even then, I knew I wanted to write in some capacity.”

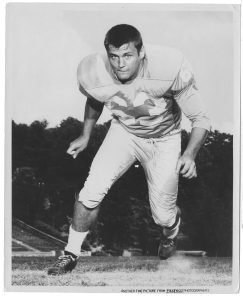

Following his passion, George played baseball and wrestled during high school. He excelled at football and was offered several scholarships his senior year. His love of reading did not, however, translate into a solid grade point average. But after being chosen to play in the annual East-West Shrine Bowl in Norfolk, Virginia, George attended Greenbrier Military School in Lewisburg, West Virginia. There he applied himself for a year in the classroom and on the playing field before signing a full scholarship to attend and play football for the University of North Carolina in 1960.

Back then, freshmen weren’t eligible for varsity play, but George enjoyed a stellar season on the UNC freshman team, starting every game and being named to the 1960 North Carolina All-State Football Team — comprised of freshmen from NC State, Duke, Wake Forest, and UNC — by the Greensboro Daily News. After a red-shirt season in 1961, he earned playing time on the UNC varsity in 1962 before suffering a severe knee injury playing against Ohio State.

That career-ending mishap forced George to take school more seriously. And his love of reading, especially the novels by William Faulkner, inspired him to change his major to English. Little did he know that soon another great love would enter his life.

“First time ever I saw her, Elizabeth was commuting to Averett College in Danville from her home across the Dan River near Milton in North Carolina,” George recalled. “She was driving her brother’s jet-black T-Bird trimmed in red. It didn’t have a muffler, so I heard her coming before I saw her. When I did, it was, from my perspective, pretty much a done deal.”

George attributes his emergence as a naturalist to Elizabeth’s influence . . . As an artist she knew how to slow down and pay attention — lessons that every would-be naturalist has to learn.

Elizabeth wanted to focus on painting, and George was still set on becoming a full-time writer. He had been visiting the Smokies, doing research for a biographical profile of Horace Kephart. George suggested that they give the Bryson City area in Swain County, North Carolina, a try.

Things have worked out. The southern boundary of GSMNP has been a fine place to live, especially if you’re a painter or a naturalist. “We’re exactly where we want to be,” said George.

End excerpt

By December of 2022, the Ellisons had put their 38 acres in a conservation easement funded through a grant from the North Carolina Land and Water Fund with Mainspring Conservation Trust of Franklin, NC. The press release said, “The easement will help protect the viewshed for portions of the Smokies, the Nantahala National Forest, and portions of the Tuckasegee River.”

Elizabeth said this was their way of “paying back what the land has given to us,” and that “finding our personal sanctuary on Lands Creek was undoubtedly more important to our personal success than words can convey.”

Earlier that year in July, a visit to Lands Creek turned a near mishap into a memory I will always cherish. By this time, George had been fighting — and I do mean fighting — Parkinson’s Disease for 17 years, and he had in many ways been keeping the upper hand. He did sometimes have a bit of trouble with getting his feet to “pick up.” But even so, he still wanted to take a walk around the property and show me his varieties of ferns.

As we set off from the old cabin down towards the creek, suddenly George pitched gracefully forward onto the ground. A small rock had impeded his steady progress, and I hadn’t reacted swiftly enough. Once he was down, I felt that I should fetch Elizabeth and my husband, John, who were working on a domestic project elsewhere on the property. But every time I started away from George to try to summon them, he commanded me not to go — and I wasn’t about to cross him.

What ensued entailed a lot of bodily contortion on both our parts — not unlike a game of Twister — but somehow eventually we succeeded in getting him upright enough to use his trekking poles to hoist himself back to a walking position. We laughed until we almost cried.

Later that day, George turned me on to William Bronk, and I close with this excerpt from his favorite Bronk poem, “A Bright Day in December,” dated 1962–63:

The thing we have to live

with, the last thing, is it is all

here, and was, and will be, is all there is.

Nothing is coming but what is already here

as this light, now, in the darkest time

(and nothing here that ever needed to come)

at once, too much for us and not enough.

Elizabeth continues to paint, and her work can be seen at elizabethellisongallery.com. She suggests that those who want to recognize George plant a native wildflower garden or support Great Smoky Mountains National Park by joining or giving to one of its partner organizations such as Great Smoky Mountains Association. Learn more and purchase the spring 2021 issue of Smokies Life with the full Ellison profile.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.