I never imagined a pumpkin might mean the difference between life and death. The only time I’ve ever paid the slightest attention to the large, lopsided orange fruit is during jack-o’-lantern and pumpkin pie season. Then I met Robin Goddard during my stint as the 2022 Steve Kemp Writer-in-Residence and was, as I have so often been, reminded how much there is to learn in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

The retired Maryville, TN, teacher began volunteering in 1969 and is recognized as one of the longest-serving volunteers in the park. Goddard possesses a certain sturdy Appalachian exuberance and gentle, southern-peach-pie attitude, which she brings to life during her incredibly popular tours of the Little Greenbrier School and Walker Sisters’ house. Both are accessed near the Metcalf Bottoms Picnic Area.

Everyone, according to Goddard, is a storyteller. “The only difference between me and other people,” she says, “is that my stories happened in what is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park.”

She hadn’t thought much about those stories until after she was married and leading a hike with friends to the Walker Sisters site. “I started sharing something I remembered when my husband, Jim, chimed in, surprised that I knew the sisters personally,” she says. “That’s when I realized that if you don’t tell a story, history is gone.”

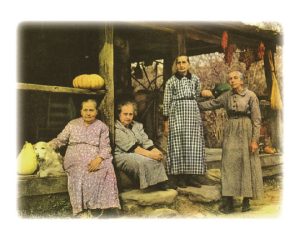

Goddard’s history became intertwined with the Walker Sisters at the tender age of four. While countless families left their homes following the purchase of property that would become the national park, the five remaining unmarried sisters were among a small group who were given a special lifetime lease, allowing them to live the remainder of their lives in the log cabin in which they’d been raised.

One of the sisters’ best friends was Goddard’s neighbor Elsie Burrell. “Elsie helped the sisters every year with the harvesting and planting,” Goddard remembers. “My dad used to make the drying racks for the family, and Miss Elsie offered to take them over with her one day. Not only did he say yes, he asked her to take me with her too, to keep me out of trouble.”

From that time on, Goddard lived with the Walker Sisters for six to eight weeks each year, sleeping on a trundle bed in the primitive cabin that possessed neither indoor plumbing nor electricity. “The sisters continued to live as their family had in the 1800s,” says Goddard.

The memories of the sisters and planting season remain vivid. “When I was a little girl, Margaret, the eldest sister, reminded me somewhat of the witch in Hansel and Gretel,” Goddard says. “She always scared me a little. When she said to do something, you just did it.”

As the eldest, Margaret took the lead, walking a straight line in each garden row, using her stick to create holes every 12 inches. “Because I was the smallest and youngest, my job was to place the heirloom seeds in those holes,” says Goddard. “Next, sister Louisa (pronounced Loo-eye-zuh) or Miss Elsie would follow behind me, filling the hole with chicken poop. Whoever was behind that person covered the hole. I remember, too, the marigold seeds that were placed in between to control bugs and the green beans we planted at the base of the corn to allow the runners to climb the stalks.”

Given her youth, Goddard also had the wearying job of running back and forth to the spring house to retrieve crocks of sauerkraut, pickled beets, and onions, as well as root vegetables.

The lard the sisters used for cooking and making lye soap came from rendering the hogs their brothers butchered for them. “There was always a tin of it on the stove, Goddard says. “Margaret used it and made the best fried pies and apple stack cakes. If you were there at mealtime, they served themselves first, and guests were invited to fill their plate after them. They always had plenty of food.”

If you ask her to elaborate on some of her most memorable times, Goddard is quick to talk about the sisters’ gorgeous pumpkin mounds whose vines had the most beautiful blossoms. “I will never forget the year I pulled some of those blossoms and wound up with Miss Elsie’s handprint on my leg forever.” When the chastised but curious child asked the sisters why they cherished their pumpkins, she learned the missing piece of the story that forever changed how she, and now I, look at them.

Before he married, the sisters’ father, John, fought for the Union during the Civil War. He was captured and sentenced to the overcrowded and unsanitary Andersonville Prison, where approximately 13,000 prisoners died before the war ended. Goddard recalls, “Louisa told me a farmer tossed pumpkin slices to the prisoners, keeping the malnourished men from starvation. ‘We wouldn’t be here if not for that farmer and those pumpkin slices,’ Louisa said.”

Suffice it to say, Goddard never picked another pumpkin blossom.

While she considers the sisters to be national park “movie stars,” her own star also shines brightly. When the producers of Barnwood Builders wanted to create an episode around the Walker Sisters cabin, they naturally reached out to Goddard to share her personal experience and insights. The popular television series documents a team of builders who breathe new life into historic barns and log cabins. The Walker Sisters episode aired in late February, and a second episode about their cantilevered corn crib will air on March 30 at 9 p.m. on the Magnolia Network.

I have no doubt Goddard, with her warmth and wisdom, will be the highlight of the television program, and I can’t encourage park visitors enough to attend one of her in-person programs if your schedule allows. She can be found at the Little Greenbrier School on Tuesdays between April 18 and October 31. If you’re anything like me, you’ll discover the deeper you dive into Smokies’ history, the more deeply you’ll appreciate the park.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.