I was perched one day on the stoop of my tiny apartment on the campus of Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont when an old woman walked up to me and said, “You’re sitting where my kitchen used to be.”

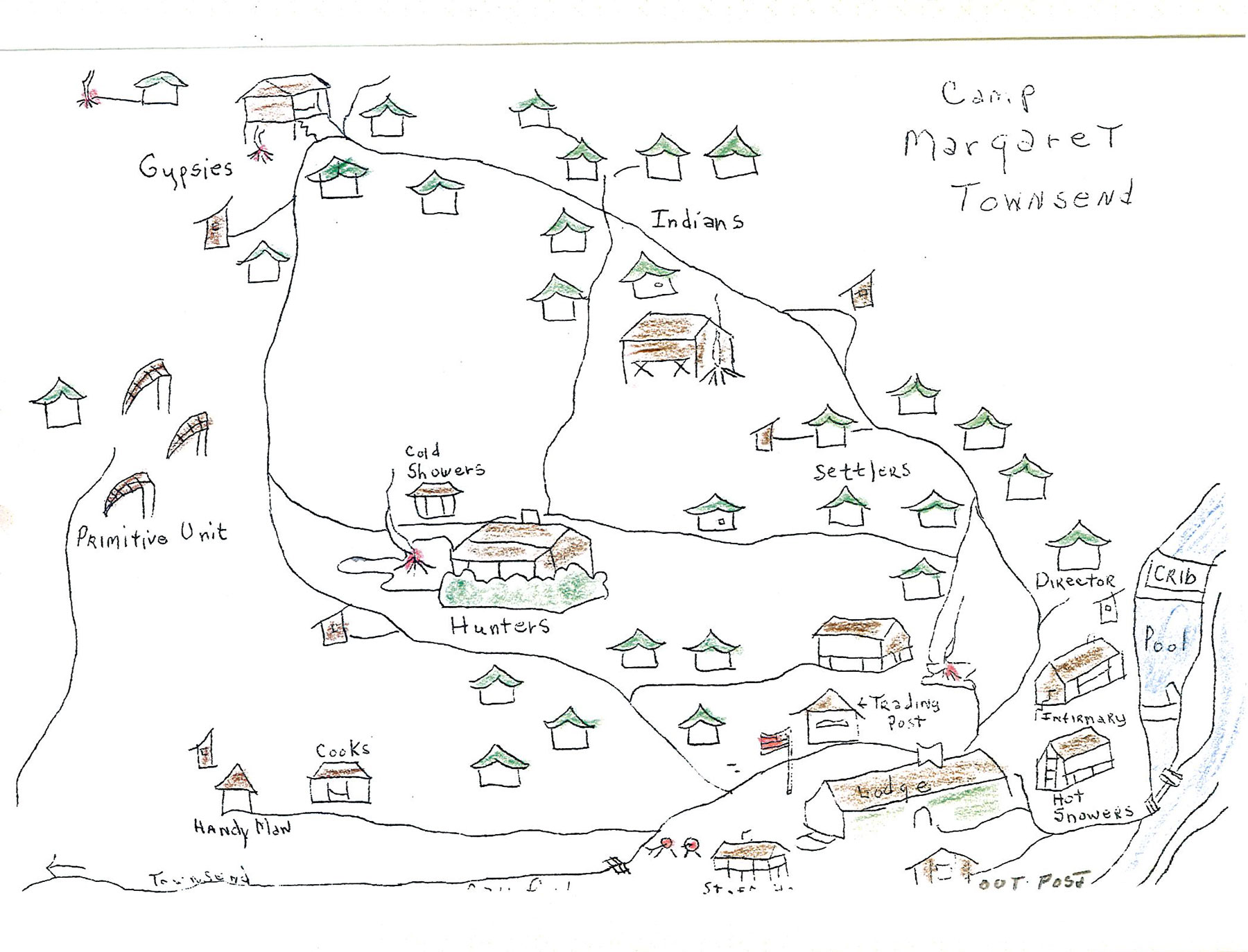

I’ve had numerous encounters over the years with such individuals, each of whom spent time at Camp Margaret Townsend, which operated in Walker Valley from 1925 to 1959. The woman told me that the long brown building where I was living at the time was located on the former site of the chow hall. She’d served as a cook during her summers at the Girl Scout camp and, like many others, was visiting her old stomping ground.

Camp Margaret Townsend was founded under the visionary leadership of Mabel Ijams, a Knoxville Girl Scout Council member and daughter of Little River Lumber Company president “Colonel” W.B. Townsend. While searching for a location for a summer camp in the early 1920s, she fell in love with the rustic site once inhabited by Will and Nancy Walker, who had died several years earlier.

Mabel convinced her father to donate the Walker family’s old land, now owned by the lumber company, and named the camp for her mother, who died unexpectedly in 1923. Margaret Townsend had been beloved by logging families for her generosity toward their children at Christmastime when she visited logging camps to deliver gifts. Now her name would be enshrined in a summer camp that would bring thousands of youngsters to the mountains over the following decades.

In the early days before an automobile road was built, campers arrived by logging train, riding the red caboose. Some hardy souls traveled five miles by foot from Townsend. Only 40 girls attended the first summer. However, nearly three hundred campers would occupy 26 tents in just a few years.

The enrollment cost was $7 per week, and camp lasted from late June till the middle of August. Many girls stayed for as long as a month. Activities ranged from hiking to crafts to games and horseback riding. “Every day, there was something about nature,” said long-time director Alice Heap.

Just as there was no indoor plumbing, neither was there electricity. Daily chores were called “Kapers” and included chopping firewood and hauling water from a nearby spring.

While some campers came from the local area, most were city girls. A pair of young ladies from New York City livened things up one year. The polite and indirect manner in which Southern girls would say, “It’s time to clean the dishes,” was replaced by a far more direct command: “Clean the dishes! Now!”

Rosie, a Black woman who washed the girls’ clothes, was revered at camp. Of her own accord, she gave out candy to any homesick child. When she passed away suddenly, scouts attended her funeral, where they gave “resolutions,” a tradition that involved sharing memories of the deceased, including Rosie’s big laugh.

Girl Scout Island, located in the nearby Middle Prong of the Little River, was a favorite spot for campers. Sunday school was often held there, and girls especially loved a large boulder located at the tip of the island called, naturally, Girl Scout Rock.

One morning the scouts discovered that loggers had drilled three holes into their rock for the purpose of dynamiting it. The scouts held a meeting and decided to save their rock by picnicking on it every hour of the day. The loggers waited for the girls to leave, but they never did. The next day the men arrived early, only to find the scouts had arrived even earlier. When it happened again on the third day, the crew gave up and let the girls keep their rock rather than sacrificing it in the name of “progress.”

The story doesn’t end there. Both in 1994 and 2003, major floods raged through Walker Valley. During each event Girl Scout Rock diverted floodwaters around the island.

According to one hydrologist, the island’s topsoil and everything living on it would have washed away if the girls hadn’t saved the boulder. They thought they were only saving a boulder, when they were really saving the entire island.

The girls didn’t know the impact they were making at the time, but they knew the impact Camp Margaret Townsend had on them. “My experiences there were truly formative and are how I came to know and love the Smokies so dearly,” says Margaret Weirich, who attended the camp in the 1950s.

The Girl Scouts could wear out the sturdiest of men. Sherman Stinnett was Will Walker’s grandson and was the caretaker for many years. He once attached a pipe to the steep tributary Tremont staff call Faultline Falls, which runs down the face of Fodderstack Mountain. Sherman positioned the pipe across the river to supply water for the chow hall. Plenty of other projects kept him busy all summer long.

An early camp director was Adelie Clemens, cousin of Samuel Clemens (a.k.a. Mark Twain). When a rattlesnake slithered onto a camper’s bed one day, she alerted Sherman, who was not keen on trying to remove it. His solution was to fire a gun through the bunk and kill it. Adelie demurred, saying she wanted to skin the snake and cook it for supper.

“You’re not going to cook that snake,” Sherman insisted. So exhausted was he by his caretaking duties after each summer that when asked what he did the rest of the year, he said, “I just set.”

Needless to say, the National Park Service does not sanction killing snakes or using firearms in the park.

The national park granted Camp Margaret Townsend a 20-year lease in 1940. When it expired in 1959, the Tanasi Girl Scout Council opened a new camp on the shores of Norris Lake. Leaders and scouts were permitted to take tent platforms and anything else that could be carried out.

The only thing left behind was the mess hall. When it was put up for sale and no one bid on it, park superintendent Fred Overly ordered it burned to keep poachers and vandals from making further use of it. A Job Corps Center was constructed on the site in the next decade when a modern dining hall with electricity replaced the old one. Thirty-some years later, following the demolition of many of the Job Corps buildings, the living quarters for Tremont staff where I once lived were erected.

The years pass by. The memories stack up, and Girl Scouts, now in their 70s, 80s, and 90s, sometimes stop by to share them. “Tell me more,” I say, always grateful when they do.

If you have memories or information to share about Camp Margaret Townsend, Margaret Weirich would love to hear from you at 68mmw78@gmail.com.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.