Three years ago, researchers from St. Cloud State University in Minnesota captured the attention of biologists around the world with a surprising discovery. After observing a number of frogs, salamanders, and newts under blue and ultraviolet light, the team found that every amphibian they tested could glow, or ‘biofluoresce.’

Although biofluorescence has been studied predominately in marine animals, the research revealed the trait to be much more widespread among amphibians than was previously known. Of the amphibians tested, several salamander species exhibited particularly striking biofluorescent patterns in response to blue light. Now, as the scientific community continues to explore the implications of such a fundamental fact of biology hiding in plain sight, a new study conducted in Great Smoky Mountains National Park could help explain how and why some salamanders glow.

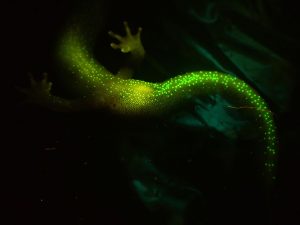

In a paper published last month in the journal Scientific Reports, biologists Jonathan Cox and Benjamin Fitzpatrick describe the biofluorescence of the southern gray-cheeked salamander (Plethodon metcalfi)—a salamander found only in the Smokies and some high-elevation areas in Western North Carolina. After carefully capturing a number of southern gray-cheeked salamanders using sterilized plastic bags and gloves, the biologists exposed the salamanders to blue wavelengths of light while photographing them in a dark environment using specialized camera equipment.

“Both males and females have this dull green glow across their entire bodies, but under normal viewing conditions, this species is totally inconspicuous. It’s just black and gray,” says Cox. “For biofluorescence, there needs to be an outside source of light. That light energy is absorbed and then reemitted by the organism at a lower wavelength or color—in this case, blue is absorbed and reemitted as green.”

The study is the first to confirm and document biofluorescence in the southern gray-cheeked salamanders, but perhaps the most important finding of the study is the difference the biologists noticed between male and female displays.

“For the males, I like to describe it as a starry-night pattern on the stomach. That pattern extends from the tip of his tail up to his throat, speckled the whole way down,” says Cox. “The female’s stomach doesn’t have speckling at all for the most part, unless the female is really big. And even in that case, the speckling only extended from her cloaca down her tail.”

This difference, which biologist refer to as “sexual dimorphism,” is often a strong indicator that a trait plays a role in mate selection. And according to Cox, salamander courtship can be a complex affair involving chemosensory signals, pheromones, and, for the southern gray-cheeked salamander, a choreographed “foot dance.”

“We noticed a pattern in some of these males where these speckles extended down every digit in parallel spots along each of their fingers and toes, so that’s where we think they could be using it in their foot dance to get the female’s attention,” says Cox. “Potentially this whole time they’ve been biofluorescing to one another, and we just had no idea.” Salamanders’ eyes may be much more attuned to register fluorescence than human eyes.

The Great Smoky Mountains have been described as the “salamander capital of the world,” home to at least 31 distinct species of salamanders. Smokies “sallies,” as they are affectionately called, range in size from the inch-long pigmy salamander to the eastern hellbender, the largest salamander in North America measuring up to 29 inches. They can be relatively nondescript, marbled, spotted, lined, long-tailed, black chinned, or red cheeked, and they make their homes in a wide range of habitats—from caves and rocky outcrops to streambanks and leaf litter. According to Cox, the unusually rich biodiversity of the Smokies salamanders can be attributed to several factors.

“Having this really broad range of elevations, highly oxygenated streams, an abundance of microhabitats and rainfall, and lots of time led to a lot of diversification,” says Cox, who also notes that some Smokies salamanders may be particularly vulnerable to habitat disruption and climate change. “As climate warms and those high-elevation species have to move farther and farther up in elevation to find their habitat, eventually there’s nowhere to go. Those peaks aren’t getting any taller, so eventually that habitat will run out as the climate warms.”

The Appalachian Mountains are among the oldest mountains on earth. Forming some 480 million years ago, they pre-date the development of bones and Saturn’s rings. In that vast amount of time, much has changed. In fact, the fossilized remains of extinct arthropods and cephalopods from ancient seas can still be found embedded within Smokies limestone. Some biologists speculate that amphibian biofluorescence could be a holdover from this long evolutionary past.

“Different colors are filtered out as light passes through the canopy of trees, and therefore, there’s a higher abundance of blue wavelengths of light near the forest floor. That same thing happens in the water column,” says Cox. “It’s possible that this is a trait that’s just been maintained because fish also fluoresce blue, and amphibians just maintained that trait as they’ve moved onto land and evolved.”

Much more is yet to be learned about the development and purpose of amphibian biofluorescence, but as Cox and Fitzpatrick’s research suggests, the salamanders of the Great Smoky Mountains may hold important answers.

“We still don’t know exactly why they’re doing it, and we don’t know how they’re doing it, but as soon as we do, it could open up a whole new ecological paradigm,” says Cox. “They’ve been doing this for millennia—it’s this whole world that we haven’t been clued in on.”

Jonathan Cox completed his study on southern gray-cheeked salamander biofluorescence as an independent researcher working with Benjamin Fitzpatrick of the University of Tennessee, but Cox has since accepted a position as biological science technician at Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Cox and Fitzpatrick’s research was supported by the Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center near Waynesville, North Carolina, and funded through grants provided by Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association and Friends of the Smokies.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.