George Masa’s influence recognized as biography publication draws near

Throughout the National Park Service’s 108-year history, countless people have made sacrifices, taken stands, and

Throughout the National Park Service’s 108-year history, countless people have made sacrifices, taken stands, and

This April, Smokies Life received national recognition at the 2024 Public Lands Alliance Partnership Awards

Frank X Walker and David Brill share a fascination with the Great Smoky Mountains. One

As the days grow warmer and the landscape ripples with color, a growing treetop chorus

Often overlooked and underappreciated, fungi fulfill diverse ecological roles in nature. They act as decomposers, breaking down dead plant and animal material and returning vital nutrients to ecosystems. They form mutualistic partnerships, benefiting a wide range of organisms from plants to animals. Some fungi even exhibit parasitic behavior, attacking living organisms to steal nutrients and sugars.

In this article, I aim to shed light on one particularly fascinating collaboration between plants and fungi: mycorrhizal fungi. Join me as we delve into this intricate and fascinating symbiotic relationship.

Mycorrhizal fungi (“myco” meaning fungus, and “rhiza” meaning root) are fungi that form a mutualistic or beneficial relationship with plants. The plant provides sugars (or carbon compounds) produced through photosynthesis to the fungus, while the fungus provides nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous to the plant from the soil.

Many species of fungi are only known to occur in mycorrhizal relationships. This means that aboveground plant communities shape the fungal communities below them. This suggests a long evolutionary history of partnership between fungi and plants.

Mycorrhizal fungi play a particularly important role in harsh or polluted environments, where the plant host cannot grow without the help of its fungal partner. In nutrient-poor environments, the fungus will mine nitrogen and phosphorus from deep soil layers or even from rock, which will then be transferred to the plant. In metal-contaminated environments, like mine tailings, the mycorrhizal fungi can gather and store heavy metals, preventing them from reaching plant roots!

These cooperative properties of mycorrhizal fungi have made them important tools in ecological restoration. Environmental remediation with fungi is termed mycoremediation. Because most (90 percent of) plant species associate with mycorrhizal fungi, these mutualistic relationships are widespread and play an important role in carbon and nitrogen cycling in soil environments. Thus, fungi have a vital part to play in shaping our planet’s response to climate change and in maintaining stable nutrient dynamics across natural and agricultural systems.

There are two primary types of mycorrhizal fungi: ectomycorrhizal and endomycorrhizal. Ectomycorrhizal fungi penetrate the plant root sheath but not the plant cells, whereas endomycorrhizal fungi penetrate into plant root cells.

Endomycorrhizal fungi fall into three distinct categories: arbuscular, ericoid, and orchid mycorrhizal fungi. Each of these mycorrhizal types produces specific structures to exchange nutrients with their plant host, and each mycorrhizal type is known to associate with distinct linages of plants. For help with terminology throughout this post please refer to my introductory article about fungi.

Ectomycorrhizal Fungi

Ectomycorrhizal fungi form mycelial structures around plant roots, which are referred to as ectomycorrhizae. In the soil, fungal hyphae intertwine with plant root cells, creating a special structure called the “hartig net.” This network serves as the hub for nutrient exchange between the fungus and the plant.

The ectomycorrhizal form has evolved independently many times and is estimated to be more than 80 million years old. Many fungi that produce mushrooms in forested habitats are ectomycorrhizal, including fungal genera like Amanita, Russula, Lactarius, Cortinarius, and Inocybe. Ectomycorrhizal fungi can form mutualistic relationships with coniferous trees (e.g. pine, fir, spruce, hemlock, etc.) and some deciduous trees (e.g. oak, beech, aspen, hickory, etc.). Many delicious edible mushrooms like chantarelles and truffles are also ectomycorrhizal.

Endomycorrhizal Fungi

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

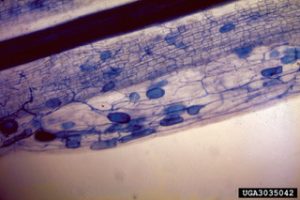

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi produce mycelial structures that penetrate the cells of plant roots, creating fan-like extensions called arbuscules. These arbuscules are the sites where nutrients are exchanged between the plant and the fungus.

These fungi do not produce mushrooms but consist of microscopic hyphae, arbuscules, vesicles (storage structures), and spores that are found below the soil surface, which means that they are not visible to the naked eye.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associate with more than 80 percent of plant species worldwide including mosses and many vascular plants. They are dominant in agricultural systems, grassland, and some forested communities and are thought to have evolved over 400 million years ago!

Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi

Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi are named after the plants they associate with, the Ericaceae or the heath family. Ericaceous plants can occur on nutrient-poor soils, which are often highly acidic and contain heavy metals. In the Smokies, Blue Ridge blueberry, farkleberry, and flame azalea are all ericaceous.

These fungi penetrate plant cells and form coiled hyphal structures, which are the sites of nutrient exchange between the plant and the fungus. Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi are also microscopic and do not produce mushrooms.

Interestingly, ericoid mycorrhizal fungi are capable of degrading organic matter in the soil to obtain nutrients for their plant host, a trait that is generally absent in other mycorrhizal fungi. The ability of ericoid mycorrhizal fungi to degrade organic matter is valuable due to the stressful and nutrient-poor soils that ericaceous plants inhabit.

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi are a small subset of fungi that associate with Orchidaceae or the orchids. These fungi produce a coiled like structure within plant cells called a “peloton,” which is where nutrient exchange between the orchid and the fungus occurs.

This is a unique group of fungi that can be microscopic or macroscopic (i.e. produce visible mushrooms). Interestingly, some fungi like Russula can develop an ectomycorrhizal structure on tree roots, while also colonizing orchid roots, creating a complex flow of nutrients from trees to fungi to orchids.

Mycorrhizal fungi are vital components of ecosystems throughout the world, they improve the health of our forests, provide us with food, and regulate nutrient dynamics at a global scale. However, these fungi are directly threatened by deforestation and anthropogenetic pollution. Many scientists are actively working to elucidate the species and systems that are threatened, but time is limited prior to large environmental shifts caused by climate change.

To ensure a healthy and sustainable future, it is imperative that we strive to preserve ecosystems in their most natural and pristine state. By safeguarding these ecosystems, we not only protect the intricate web of fungi that depends on them but also foster a verdant and thriving environment for generations to come.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.