Through the fog

At 9 a.m., the air in Waynesville was a sweetly perfumed 60 degrees, and the

At 9 a.m., the air in Waynesville was a sweetly perfumed 60 degrees, and the

During the summer of 2011, billions of cicada eggs hatched inside tree twigs across the

Throughout the National Park Service’s 108-year history, countless people have made sacrifices, taken stands, and

This April, Smokies Life received national recognition at the 2024 Public Lands Alliance Partnership Awards

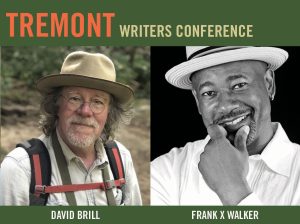

Frank X Walker and David Brill share a fascination with the Great Smoky Mountains. One

Although the word “spider” may elicit a “yuck” or an “ew” from many readers, the true nature of these oft-feared critters is not as icky as one might suppose. Arachnids provide essential services for humans and play key roles in balancing our ecosystems by keeping herbivorous insects in check.

At the dawn of 2023, it had been 14 years since a new-to-science species of spider had been discovered to live in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. But that changed in February when Marshal Hedin and Marc Milne published their comprehensive study of one Appalachian spider genus: Nesticus, a group commonly referred to as the scaffold web or cave cobweb spiders.

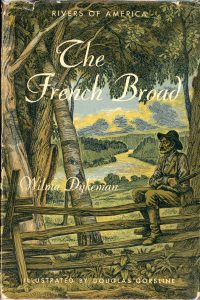

In their 130-page scientific paper tracking the evolution of the Nesticus genus, Hedin and Milne describe a total of ten spider species that are new to science—never documented before. Three of these exist in the Smokies, and one is a creature they named Nesticus dykemanae to honor Southern Appalachian writer Wilma Dykeman.

“We were generally inspired by her books and then, upon further research, her life and work in environmental and social justice in the region,” says Hedin, a professor of Biology at San Diego State University and director of the SDSU Biodiversity Museum. “Apropos because Dykeman focused on water, this species is restricted to just a few locations in the direct vicinity of the headwaters of the West Prong of the Little Pigeon River.”

The paper’s etymology entry on Nesticus dykemanae reads: “Named to honor Wilma Dykeman (1920–2006), a writer, speaker, teacher, historian, and environmentalist who spent most of her life in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. Mrs. Dykeman was devoted to social justice and environmental integrity, discussing Appalachian water pollution in her classic 1955 book The French Broad, and sharing a social justice award in 1957 for her co-authored book Neither Black Nor White.”

The other two new Smokies discoveries were also named for people who inspired the authors. Nesticus binfordae honors Dr. Greta Binford, an arachnologist recognized for her spider research and her leadership in making the American Arachnological Society more diverse and welcoming. Nesticus cherokeensis was named to honor the larger Cherokee Nation and can be found near the Qualla Boundary, home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

“These discoveries are thrilling,” says Will Kuhn, director of science and research for Discover Life in America, which has been studying and recording all Smokies species and their relationships for a quarter of a century. “The last new-to-science spider found in the park was Oreonetides beattyi, described in 2009, and the last new-record spider, Acanthepeira stellata or the starbellied orbweaver, was found by a park intern named Kelly van Assendelft in 2021.”

Park entomologist Becky Nichols, who supervised van Assendelft, was also excited to read Hedin and Milne’s study.

“These are commonly known as scaffold web spiders or cave cobweb spiders, which are not just found in caves but can also live in moist, rocky areas,” she says. “These spiders have a comb of serrated bristles on their hind tarsi (or feet) that are used to pull silk bands from their spinnerets or silk-spinning organs.”

Kuhn and Nichols say that Hedin and Milne’s discoveries bring the total count for the park up to 553 spiders known to the Smokies, including 274 that have been discovered since the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory began cataloging species 25 years ago. There is now a whopping total of 43 new-to-science spiders in the park.

Spiders are part of a larger group of species called arthropods that provide the life support systems that the whole terrestrial biosphere relies on. According to Kefyn Catley, who conducted research as a professor of biology at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina, and has studied the evolutionary biology of spiders on four continents, “Without them it has been estimated that almost all life on land—including humans — would go extinct in nine months.”

Hedin studied Appalachian cave spiders for his PhD and first became interested in arachnids through conversations with Dr. Frederick Coyle, professor emeritus of biology at Western Carolina University and a longtime member of Great Smoky Mountains Association. In the late 1990s, Coyle and his WCU students found 517 species of spiders during an intensive three-year survey funded by the National Science Foundation.

“The spider fauna of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is better known than the spider fauna of any other US national park,” Coyle says. “Thanks to the efforts of Marshal Hedin and others since our work, the total species count has grown considerably.”

Kuhn says that Discover Life in America doesn’t yet have a good total estimate for the number of spiders they expect to find in the park. “But I’d bet that there are at least a few dozen more species out there waiting to be found.”

Hedin is quick to point out that, basically, all spiders are harmless to people, with less than 0.1 percent being medically harmful. The only spider native to this area that can envenomate humans is the black widow, and fortunately, like most spiders, these are shy and retiring and do not threaten people.

“The vast majority of spiders are in fact greatly important to humans, consuming 400 to 800 million metric tons of insects per year,” he says. “Of course, many of these insects that spiders consume would be somehow harmful to people, consuming crops or vectoring disease. In this way, spiders are the ultimate predators of many pestiferous insects; this is what they evolved to do!”

As most everyone knows, spiders also make silks that are remarkable biomaterials, and with help from human ingenuity they may provide solutions to many of the problems we face today. Spider silks are already being used in biomedicine.

“In the end,” Hedin says, “spiders are in fact immensely beneficial to humans. Plus, they are just remarkable little animals, and often quite beautiful.”

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.