Late last month, I was lucky enough to catch a special musical performance in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It was a fine morning in high summer, and on the back porch of the Oconaluftee Visitor Center near Cherokee, North Carolina, a four-piece string band launched into the first swirling notes of an original composition. Holding the center of the stage and letting his banjo ring out over the supporting guitar and bass was the group’s leader, Tray Wellington.

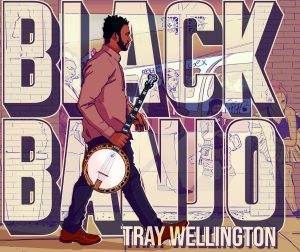

Originally from Western North Carolina and currently based in Raleigh, Trajan “Tray” Wellington is a rising star in the world of contemporary bluegrass. Through his performances at national bluegrass festivals, touring with the band Cane Mill Road, and the release of his latest album, Black Banjo (2022), under his own name, Wellington has been steadily gaining the attention of his peers thanks to his technical mastery of the banjo as well as his forward-leaning embrace of influences that stretch traditional bluegrass into the realms of jazz and contemporary rap and hip hop.

Twice, in 2022 and 2023, Wellington has been named a finalist for the International Bluegrass Music Association’s New Artist of the Year award, and in 2019, he received the association’s Momentum Instrumentalist of the Year award. As a young Black artist working within a genre historically dominated by White musicians, he has also been featured on CNN’s United Shades of America. The Tray Wellington Band’s performance in the Smokies was part of a celebration hosted by the park’s African American Experiences in the Smokies project—an ongoing initiative begun in 2018 to uncover and share previously untold stories of Black life in and around the park.

“I love this area,” Wellington told me after the show. “It’s where I’ve learned a lot of music and met a lot of people I still work with today. It’s still very important to me and somewhere I still consider home just as much as Raleigh.”

Having grown up in nearby Ashe County, North Carolina, Wellington remembers making regular day trips to the Great Smoky Mountains and passing through Wilkesboro on his way to pick apples with his grandfather.

“Some of my earliest memories are in the Smokies just riding through and listening to music on the way up and making a whole day out of it,” said Wellington. “My grandpa never played music, but we were always listening, and it kind of gave me a love for music. We’d listen to a little bit of rock, a little country, some western swing stuff, some bluegrass—a little bit of everything.”

Echoes of that eclectic listening can still be heard within Wellington’s albums and live sets. While his original compositions generally fall into the realm of progressive bluegrass or bluegrass-jazz fusion, he might also choose to include a traditional fiddle tune like “Half Past Four,” a rendition of a jazz classic like “Naima” by John Coltrane, or a cover of something more contemporary like Kid Cudi’s “Pursuit of Happiness.” As he curates each release and performance, Wellington takes care to draw on traditions while also pushing the boundaries of what audiences might typically expect of a bluegrass band.

“We don’t want to lose these songs. It’s part of carrying those traditions on,” said Wellington. “Also, people want to be able to know a song every now and then. If you do a song they know, they’re more willing to have an open ear to what you’re doing.”

On the other side, Wellington is especially conscious of the need to reach younger listeners and those, like himself, who haven’t always seen themselves reflected in the bluegrass tradition.

“There’s still this lack of representation within bluegrass,” said Wellington. “When it comes to people of color, LGBTQ+ people, people from different backgrounds, there aren’t many artists in bluegrass trying to bring that in.”

Working in a cover of an artist like Kid Cudi into his set is a way Wellington can honor his own diverse musical interests while also building a bridge to new audiences.

“That’s what folk music is, you know?” said Wellington. “It’s music that brings peoples together from all different backgrounds.”

The Appalachian landscape itself is also a perennial source of inspiration for Wellington and his bandmates. “If we’re trying to do a writing session we’ll try to get away and go to some place that’s beautiful,” said Wellington. “You need to find that calm place.”

As my conversation with Wellington came to a close, an elk buck galloped across the open field where his audience had just been standing. Soon after, a rooster wandered over from the park’s Mountain Farm Museum to let out a cheerful crow in the sun.

“This is an amazing spot to play music,” said Wellington. “All kinds of people are coming here every day—it’s a great opportunity.”

Wellington’s performance at Oconaluftee was thanks in large part to Antoine Fletcher, the park’s science communicator and the lead of the African American Experiences in the Smokies project that coordinated the event with the financial support of park partner Friends of the Smokies.

“As I stood there in the heart of Appalachia and listened to Tray play his latest album, Black Banjo, I immediately understood the importance of the connection of African Americans and Appalachian music,” said Fletcher. “The way he plays is not from days of training but from his lived experiences in the mountains. Every strum of the banjo tells his story and deep connection to the Smokies.”

An interview Fletcher conducted with Wellington on the day of the concert will be shared soon on the park’s growing African American Experiences oral histories webpage. To learn more about the project and listen to other oral histories, find the project page at nps.gov/grsm under “Learn About the Park.”

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.