This article was originally published in 2020. We are sharing again in honor of Horace Kephart’s birthday, September 8, 1862.

“Mountains! Think of them; speak of them; look upon them!… Here they are in all their majesty and abundance.”

These words were written in 1905 by Isaiah Kephart, who supported his son Horace in a retreat from society at a difficult time. They are words that could easily be said aloud by any of us as we look around and feel astounded anew each day when we see the mountains that we have made our home.

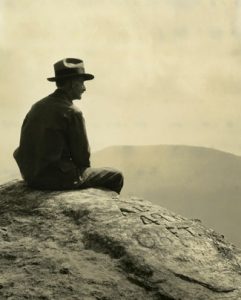

The mountains ground us, they give us energy, comfort, solace, and the strength to endure—and learn from—solitude. When Horace Kephart was at his wit’s end, he distanced himself from others and got back to the basics in these mountains.

“It is one of the blessings of wilderness life that it shows us how few things we need in order to be perfectly happy,” he wrote while living for about three years “alone in a little cabin on the Carolina side of the Great Smoky Mountains, surrounded by one of the finest primeval forests in the world.” He was hitting his stride creatively, working on The Book of Camping and Woodcraft, which would be published in 1906. In it he would invoke his mentor, known as Nessmuk, who wrote, “We do not go to the woods to rough it; we go to smooth it—we get it rough enough in town. But let us live the simple, natural life in the woods, and leave all frills behind.”

When Kephart went to the woods, he had been getting it rough enough in town. The complex story behind his choice “to leave the exhausted air of cities, the imprisoning walls, the din and strife, the jostling of unsympathetic crowds” is described in detail by George Ellison and Janet McCue in Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography. But when Kephart came to the Smokies, life became simple again.

Just as he described in Camping and Woodcraft, Kephart fished, shot rabbits and squirrels, cooked on a fire, fried cornbread, beans, ramps, and potatoes, and gathered chestnuts. He worked a garden and made his own rustic form of bitter coffee. From Our Southern Highlanders, we know that he also made friends near his cabin and visited them to purchase supplies and learn about their lives, so he was not completely isolated. But he spent a great deal of time alone, with few possessions or distractions, which allowed him to write the books and magazine articles that would change the course of history.

At this time, the Smokies was a wilderness that had been taken from the Cherokee only 60 some years earlier. Settlers were moving in along with big logging companies, outlanders ready to exploit the land and its resources. What remained unharmed was the most spectacular old-growth forest in the east; but not far from any pristine parcel, a large swath would have been clear cut.

Kephart could see that if something wasn’t done, soon it would all be leveled. A seed of advocacy was being planted that would later sprout and finally blossom a decade later when he began to wield the mighty power of his pen in defense of a park. He would write countless magazine articles and persuasive letters, convincing both politicians and the public that the Smokies should be a park because of its inspiring scenery, biodiversity, abundant springs and streams for camping and fishing, proximity to population centers, and room for millions of visitors. “I owe my life to these mountains,” he wrote, “and I want them preserved that others may profit from them.”

In advocating for preservation of the Smokies, Kephart made a substantial contribution to our region. In Our Southern Highlanders he advanced the nation’s understanding of Southern Appalachian people. Camping and Woodcraft shaped the outdoor recreation industry on a global scale. None of it would have been possible without a dramatic withdrawal from society and its conveniences.

Kephart made a choice: rather than end it all, he would start over in another place—in the mountains. He put into practice the concept of Creatio ex nihilo, the idea that something can come from nothing. When we are forced to slow down, live with fewer frills, conserve our resources, smooth out the rough edges—then the distractions that normally subvert the creative process can fall away. In stillness, we have a rare opportunity, as Kephart did, for growth.

By 1928 Kephart’s efforts had succeeded in making it possible to create Great Smoky Mountains National Park. “It was a big undertaking,” he wrote, “and beset with discouragements of all sorts; but we’ve won!… Within two years we will have good roads into the Smokies, and then—well, then, I’ll get out.”

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.