In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, law enforcement rangers regularly patrol the roads and trails responding to various incidents, medical emergencies, and search-and-rescue missions—all involving inherent dangers. A prime example of this dedication to public safety is that of Smokies park rangers Bill Acree and Dave Harbin, who survived a helicopter “mercy” mission that went terribly wrong on the cold morning of January 3, 1978.

On that fateful day, Acree lifted off from Cades Cove in an army “Huey” helicopter along with Harbin and other personnel on a mission to locate a missing airplane. NPS staff had received an emergency locator ping from a small, twin-engine Cessna 421 that had been carrying five passengers before it disappeared somewhere in the surrounding mountains.

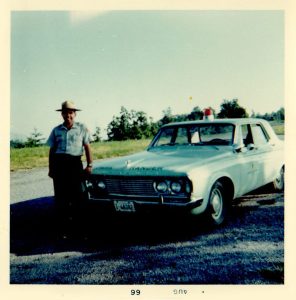

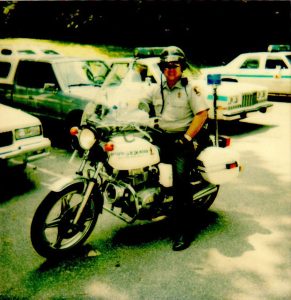

Acree was an experienced ranger, and before coming to the Smokies, he had served in the Vietnam War and as a full-time protection ranger and recovery diver at Lake Mead National Recreation Area, a site known for many high-intensity incidents. In the Smokies, he’d also responded to many incidents and had even been on a helicopter flight a year earlier that made an emergency landing in the Smokies backcountry. So, he was no stranger to danger.

But Acree knew he was in grave danger on this January 1978 mission when he heard a loud pop as the chopper ascended and neared Wolf Ridge. He then felt a loss of power and a sinking sensation as the chopper fluttered. With rising concern, he heard the pilot yell, “Mayday!” over the intercom and heard the crew chief yell, “We’re going down—prepare for impact!” The pilot valiantly tried to keep the chopper’s nose up, but the ship fell hard into the dense forest. Acree heard terrible sounds of crunching and sheering metal as the craft’s rotors were ripped off. Then it inverted and slammed into the frozen earth, nose first.

In a recent interview in his home, Acree described the incident to me: “As I realized the chopper was falling, I thought of my family and what would happen if I didn’t survive. I tightened my seat belt and said a quick prayer.” His description of the helicopter’s descent is harrowing.

“As we fell, I remember watching the trees get closer until the impact,” he recalled. “When we hit the trees, I remember a whirling, blurring motion, and then there was the heavy impact, then blackness. When I came to, I was upside down. My right foot was twisted behind me, and the leg was floppy and broken.”

Acree realized he was seriously injured and the flight crew appeared to be dead. He also realized the chopper’s engine was still running, and he smelled fuel and hydraulic fluids. He and Harbin, who was less injured, knew they needed to get out. The only exit was a busted window below Acree, so he struggled in great pain to lower himself and crawl out so Harbin and another survivor could exit. Acree located his park radio as he crawled out, and he and Harbin made calls for help.

“When I got out,” Acree continued, “I laid on the ground and had trouble breathing due to a punctured lung, broken ribs, broken leg, and what I figured was a broken back and broken shoulder blade. I knew I had to get away, so I pushed myself a short distance. There was a four-foot cliff nearby, so I planned to roll off it and take my chances if fuel ignited.”

About an hour and a half later, an army medic descended from another chopper to assist. He and Harbin dragged Acree away from the chopper. Still later, Dr. Robert Lash, medical advisor for the Smokies, and others arrived and provided emergency aid while responders worked to clear an extraction zone.

After several hours, Acree was packaged on a litter and hoisted to a medical chopper and flown to the University of Tennessee hospital in Knoxville. He arrived there four and a half hours after the crash. Ranger Harbin, though injured, made it to a landing zone for later extraction.

Acree spent the next ten days in the ICU, where doctors treated his multiple serious injuries while considering an amputation of his right leg. Fortunately, this was averted. He was hospitalized for two months and spent another ten months in surgery and rehab until he returned to light work in the Smokies, one year and three days after the crash. Harbin, his fellow passenger, returned to work in the park months earlier.

Ever the intrepid ranger, Acree ultimately resumed full duty in a supervisory role. Later, he became a criminal investigator and one of the first special agents in the entire National Park Service, working closely with US district courts in Tennessee and North Carolina on serious criminal prosecutions before retiring in 2001.

Interestingly, Acree told me the chopper’s engine hummed loudly for two hours after the crash, providing an eerie background to the gruesome scene. He also said a later investigation determined that a fuel system part had malfunctioned, causing the crash.

Today, Acree credits park ranger Dave Harbin, Dr. Lash, and the first responders and hospital staff for saving his life. He feels a deep sadness for those who perished in the incident: Capt. John Dunnavant, Capt. Terrance Woolever, Sgt. Floyd Smith, and Lt. Col. of the Civil Air Patrol Ray Maynard. None of the passengers aboard the private airplane had survived the earlier crash. The “mercy” mission that Acree and the others attempted ultimately ended up as a nightmare, with the search-and-rescuers becoming the rescued.

“I don’t think the general public really comprehends the serious risks that protection rangers face in the Smokies,” Acree said. “For most folks, the Smokies are a place of fun, natural wonder, and recreation. But every day, protection rangers put themselves in potential serious danger to protect the safety of visitors in the Smokies. We should all be extremely thankful for their work.”

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.