Editor’s note: This is the first of two articles revisiting a notorious murder in the community known as Chestnut Flats in Cades Cove and the dangerous but lucrative enterprise of distilling illegal spirits in the Great Smoky Mountains prior to the creation of the national park.

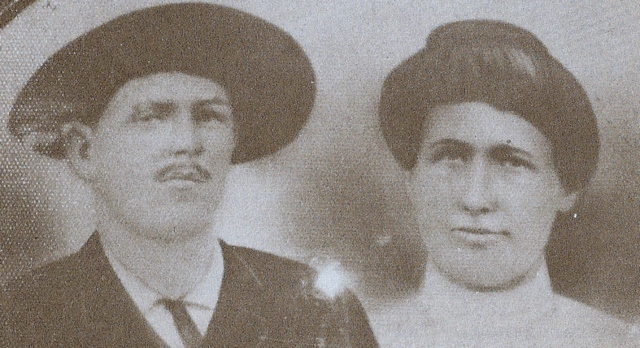

Late afternoon, December 11, 1897, George Washington Powell Jr. was ambushed, shot, and killed at his home in Chestnut Flats while playing in his yard with his three young children.

Violence was not unusual in Chestnut Flats, an enclave within Cades Cove. Located on the southwest edge of Cades Cove now bisected by Parson Branch Road, the community was initially settled by the Burchfield and Powell families soon after the Civil War. George Powell Sr., uncle to George Powell Jr., operated an orchard and both legal and illegal distilleries. When Tennessee outlawed whiskey manufacture in 1878, Powell continued his business as an illegal operation. The Burchfields, led by patriarch Sam Burchfield, were also involved in the making of illegal whisky.

Although accounts of the community vary, Durwood Dunn in Cades Cove: The Life and Death of an Appalachian Community writes that the Flats became a haven for lawless behavior. Drunken brawls were not uncommon, prompted by fights over “cards, cock-fighting, shooting matches, or prostitutes.” The outlaw community became a haven for criminals throughout the region, increasing the violence.

Local newspapers like the Maryville Times were quick to cover any illegal activities from surrounding communities that were brought to the local courts, including periodic arrests for moonshining and even murder. Dan Pierce in Corn from a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains writes that most newspaper reports took a disapproving tone, spreading the reputation of Chestnut Flats and other mountain communities as lawless places.

It is against this background that George Powell Jr. was murdered in 1897. Hale Hughes (also spelled Hughs), son-in-law of Sam Burchfield, was arrested in March 1898 for the murder. He was subsequently convicted and sentenced to 20 years in state prison. In June 1899, Hughes wrote a letter providing the details of the crime, which was summarized along with additional information by the Maryville Times. According to Hughes, both he and Burchfield had lain in wait for Powell, determined to kill him. They were seeking retribution because Powell had testified against Hughes in a trial for distilling and selling illegal spirits.

The plan was to ambush Powell as he arrived home, but they found him already at home. Hughes and Burchfield took up different spots near Powell’s house, but according to Hughes, it was Burchfield who actually shot him. Hughes did admit that he would have shot Powell if “he had passed his way.” Powell was able to stagger to his cabin, where he died surrounded by his wife Martha and three young children. His terrified wife, who was pregnant with their fourth child, barred the door, afraid to venture out for help until the next morning since the neighbors lived several miles away. Powell was just 26 years old at the time of his death.

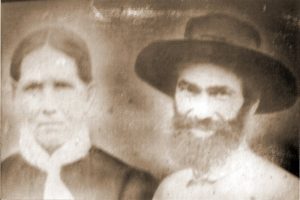

After the letter from Hughes was read by the authorities, Sam Burchfield was brought from his mountain home and charged with the murder of George Powell Jr. The Maryville Times described Burchfield as a 60-year-old man over six feet tall with long black hair, a mustache, and a beard. The newspaper article also noted that Burchfield was a well-known moonshiner who had been found guilty in federal court several times of manufacturing illegal spirits. The local sheriff and deputies started summoning 16 witnesses who were scattered throughout the mountain region.

Despite Hughes’ letter and the many witnesses, the grand jury ultimately failed to indict Burchfield for the murder of George Powell Jr., as reported in the June 17, 1899, edition of the Maryville Times. It is a bit of a mystery how this all played out.

Did the witnesses disappear when asked to testify against Burchfield, knowing he might have murdered Powell in revenge for his testimony against Hughes? Or did Hughes’ letter look like a ploy on his part to put the blame on someone else so he could get out of jail? Or perhaps the members of the grand jury were concerned about their own safety if they were to send forward an indictment.

Whatever happened, Burchfield’s reputation underwent an astounding “makeover,” at least in the Knoxville press. As we will see in the second part of this series, Burchfield’s prior illegal activity and charges of murder would be superseded in the years following his trial as he rode a wave of renewed public interest and appreciation for the art of moonshining in the mountain South.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.