With winter finally in the rearview, most people attempting a northbound thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail this year have already started their trek at Amicalola Falls State Park in Georgia—and many have already made it to or through the 71.6 miles that fall within Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

So far in 2024, the park has issued 2,190 thru-hiker permits, a number that is likely to rise substantially as the hiking season unfolds. Last year, it issued 3,429 such permits. Over the last eight years, that number has fluctuated between 1,068 in 2020, when the park and many other public lands altered operations due to the pandemic, and 4,231 in 2017, after a pair of movie releases—Wild in 2014 and A Walk in the Woods in 2015—boosted interest in thru-hiking.

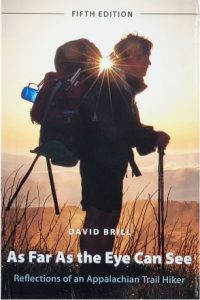

“When my trail friends and I thru-hiked the AT in 1979, we were relatively early devotees on a pilgrimage that, within a few decades, would become a popular rite of passage,” said writer, author, and hiking enthusiast David Brill, whose books include As Far as the Eye Can See: Reflections of an Appalachian Trail Hiker and Into the Mist: Tales of Death and Disaster, Mishaps and Misdeeds, Misfortune and Mayhem in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Volume 1, both sold by Smokies Life. In total, 136 people finished the trail the year that Brill hiked it—at the time, a record. In 2022, 1,440 people completed the journey.

Hikers attempting the entire 2,197.4 miles to Mount Katahdin in Maine make it to the Smokies only if they first complete the initial 167 miles from Springer Mountain, Georgia. The stretch running through the country’s most-visited national park contains some of the most beautiful—and most challenging—miles of the southern portion. The trail crosses the bridge at Fontana Dam and meanders along the North Carolina-Tennessee state line, following the ridgeline to cross or come near multiple iconic peaks, including Clingmans Dome, Charlies Bunion, and Mount Cammerer, before leaving the park close to Interstate 40.

So far, 3,906 people have registered their intention with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy to start a thru-hike at the trail’s southern terminus this year, of whom 3,598 said they planned to set out before May 1. A smaller number of people embark each year on a “flip-flop” hike near the middle of the trail in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, or for a southbound hike from its northern terminus at Mount Katahdin in Maine. These hikers typically set out a bit later in the year than northbound hikers do. Last year, a total of 4,344 people registered to start a thru-hike in one of those three locations. The true number of thru-hike attempts may be even higher, as registration is not required to hike the trail.

“North- and southbound hikers carefully time their starts for a couple of reasons, weather being one of them,” Brill said. “For northbounders, the threat of severe winter weather, particularly in the higher elevations of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, lingers into March and even April and adds an element of risk to a late-winter, versus early-spring, start. As for southbounders, later starts allow them to avoid wintry conditions that continue to grip the mountains of New England until May or even June.”

The so-called Storm of the Century, which struck the Smokies on Friday, March 12, 1993, offers a prime example of the risks hikers must weigh when scheduling their start date. With just over a week to go before the first day of spring, several feet of snow accumulated on Mount Le Conte, driving temperatures below zero degrees and stranding more than 150 hikers in the park’s backcountry.

There’s more data available than ever before on the hikers beginning their journey at Springer Mountain. This year, for the first time a digital registration method was used for hikers stopping by the Amicalola Falls State Park visitor center during the Georgia Appalachian Trail Club’s AT Base Camp, held February 15 to April 15 each year. The digital process made it easier to analyze the data gathered there.

More than 92 percent of the 2,252 people who registered in person were US residents, with the remaining hikers traveling from all over the world to hike the AT, with 22 countries represented. Two-thirds identified as Canadian, German, or British; about half of the US residents who registered came from Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, or Virginia.

People who complete the AT often describe it as one of the most fulfilling and meaningful experiences of their lives—but also one of the most difficult. The average thru-hike takes five to seven months, covering nearly 2,200 miles in 14 states and including a total elevation gain equivalent to climbing Mt. Everest 16 times.

Hikers must conquer each mile while carrying backpacks that contain everything they need to sleep, eat, and stay safe on the trail. Acclimating to this constant load can make the first few weeks of the trek extremely difficult, Brill said, both physically and mentally. Of the 1,582 hikers who had their packs weighed at Basecamp this year, the average weight was 33.9 pounds, roughly equivalent to a full-grown English cocker spaniel or 3.5-year-old boy. No wonder thru-hikers can burn up to 6,000 calories per day.

“Whittling away a 2,100-mile trek in 10- to 12-mile increments can leave hikers feeling as though they’re not making much progress,” Brill said. “It’s been my experience that the key is to savor the journey, step by step, day by day, and, for the most part, to regard cumulative mileage for what it is—a mere metric for measuring distance and one that’s much less meaningful than gauging the months-long trek in terms of experience.”

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.