Editor’s note: This is the first of Anne Bridges’ three-part series on a Blount County outlaw known as Hut Amerine and his illegal moonshining enterprise in the Great Smoky Mountains prior to the creation of the national park.

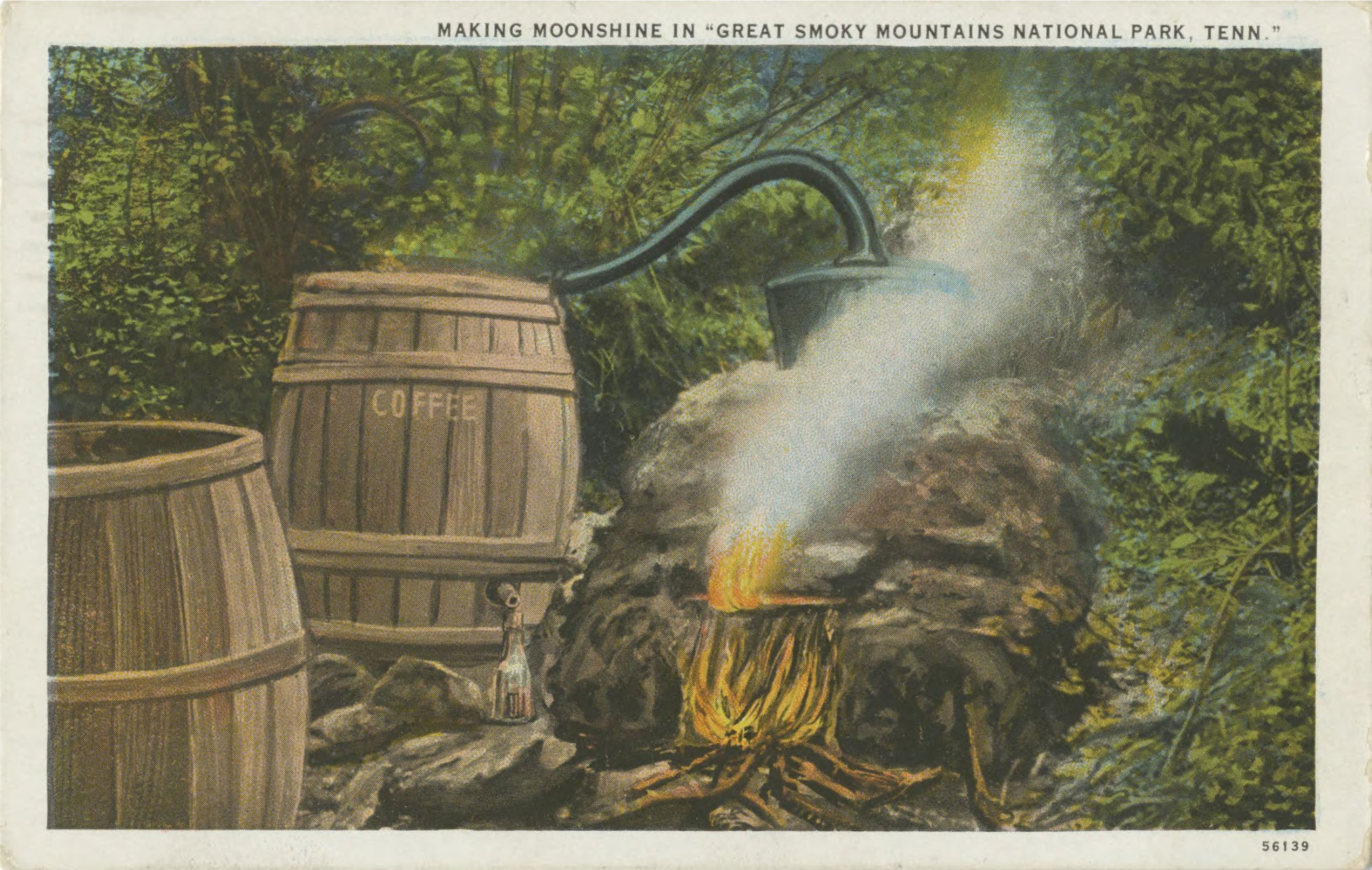

During the tumultuous American Civil War, US Congress enacted a new excise tax on whiskey, but there was little will or ability to enforce that tax in the hills of Southern Appalachia. During the war and for years in its aftermath, bootleg distillers in and around the Great Smoky Mountains continued to produce and sell whiskey, or moonshine, without registering their trade with the US government or paying federal taxes. Starting in 1877, however, tensions and fighting between federal revenue agents and East Tennessee moonshiners increased dramatically.

Green B. Raum, a former Union Army general, had been appointed as the new head of the Bureau of Internal Revenue, the agency charged with enforcing the liquor tax. According to Dan Pierce in Corn from a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains, Raum reported that at this time at least 3,000 stills were operational in the Southern Appalachian region representing a lost federal tax revenue of approximately $2.5 million annually. Raum decided that this defiance of federal law had to be stopped. In response, Congress allocated additional funds to hire deputies to assist federal agents raiding illegal distilleries.

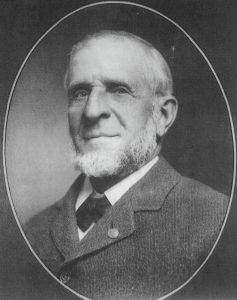

Joseph A. Cooper of Knoxville, also a former Civil War general, was placed in charge of the federal effort to locate moonshine stills and arrest the operators in East Tennessee. After several attacks against his officers, he declared war on the illegal production of spirits and sent raiding parties throughout the region capturing and destroying dozens of stills and shutting down operations, at least temporarily.

According to Pierce, agents used several methods to locate stills. They looked for worn trails that moonshiners might be using, wisps of smoke that indicated distillery fires, and soft-water streams used to produce the best whiskey. They tracked feral pigs who liked to eat the mash used for the distilling. But the best sources of information were informants, frequently neighbors or family members. Moonshiners developed a fear of outsiders, convinced they were revenue agents or that they were going to inform the authorities about their activities.

General Cooper had been made aware that Hut Amerine (also spelled Amarine), along with several associates, operated a still in Blount County near the North Carolina state line. George Atkinson in After the Moonshiners quoted William Cooper, son of General Cooper, as saying that “Amarine was chief of the Smoky Mountain operators, and was one of the most daring outlaws in the Union. We were well aware of the fact that when we found him, we would have trouble; but we had plenty of officers who were willing and anxious to meet him.”

Born in 1838, Amerine was a Blount County native. His father George was a prominent citizen who manufactured iron in Millers Cove. Hut (full name Eli Hutsell according to his gravestone) enlisted in the Union Army in September 1863 as a member of the Third Cavalry. He entered the army as a private and mustered out as a sergeant.

After the war, Amerine came home to marry Eliza Jane Waters in 1866 and establish a residence in Millers Cove. In the 1870 census, he was listed as a farm laborer. He was also engaged in an additional occupation, moonshiner, a profession obviously not included in the federal census.

An 1899 Knoxville Sentinel article described Amerine as being about medium height, heavy-set with a dark complexion. He had piercing black eyes and a dark beard. Devoid of a formal education, he was nevertheless regarded as being “keen and quick-witted.” He surrounded himself with a cadre of “boon companions who were generally men of a disreputable character.”

On August 6, 1878, General Cooper was approached by Peter Davis, a local man who offered to act as a guide to lead federal officers to Amerine’s still. A squad of six men was dispatched. In the words of William Cooper, “The still house was reached at 3 o’clock, a.m. of August 8th, and was found to be situated in a deep hollow surrounded by heavy growths of timber.”

Despite the late hour, Amerine and three other men were alerted to the presence of the officers by their guard dogs. The moonshiners quickly emptied their rifles at the federal officers. J. B. Snyder, one of the officers, was wounded in the wrist, an injury that maimed him for life. After the ambush, the officers decided to abandon the attack and return to Knoxville. Snyder returned home on the Maryville train to have his wound tended.

After the rout by Amerine and his associates, General Cooper was even more determined to arrest Amerine and put an end to his illegal whiskey operation.

Part two of this series describes Cooper’s fateful second attempt to bring the law to bear on Amerine and his associates.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.