I’d been hearing about the Public Lands Alliance Convention since my first day with Smokies Life nearly a year ago, when I arrived at my new job to find many of my colleagues jetlagged yet re-energized about their work following the 2024 conference in San Francisco. They spoke about the event in glowing terms, but I didn’t know quite what to expect when I arrived in Las Vegas, Nevada, to participate in the 2025 conference earlier this month. The city’s name conjured up images of skyscrapers and slot machines, a seemingly odd setting for a gathering of conservation nonprofits whose members are by and large more at home in natural landscapes far from city lights.

But Las Vegas, I quickly found out, is an isolated outpost of human development surrounded by a sea of public lands. Beloved national parks like Death Valley, Zion, and Grand Canyon are all within an easy day’s drive of the city, not to mention millions of acres managed by the Bureau of Land Management, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and US Forest Service. As hundreds of conference attendees and trade show exhibitors arrived from places as distant as Alaska, Hawaii, and upstate New York, the halls of the casino hotel where the convention was held began to feel a bit less artificial and more proximate to the outdoor spaces PLA is dedicated to supporting.

From its opening session Sunday evening, February 1, through its closing Wednesday, February 5, the conference was packed full of educational sessions and presentations ranging from inspirational to practical, and many were a deft combination of the two. Stories of conservation, exploration, and discovery brought to life the wonder of the wild spaces we work to conserve and helped demonstrate the tools available to do so more effectively. This was exemplified right off the bat with an opening session featuring a panel of partners who shared how they brought together a diverse group of stakeholders to successfully protect half a million acres in southern Nevada, now designated as Avi Kwa Ame National Monument. Bookending the conference was a talk from Quinn Brett, a former rock climber who continues to lead a life of adventure following a devastating spinal cord injury—her experience was also featured during a Monday evening public lands film festival—who used her own dynamic story to share how public lands can improve access for people with physical disabilities.

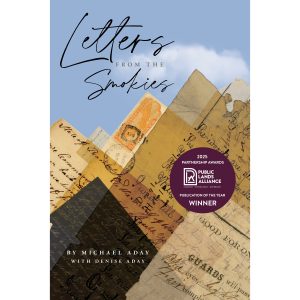

Between these two bookends, I attended sessions including a collaborative roundtable discussion with other communications professionals, a presentation about how to involve tribal communities in public lands work, and an engaging talk from podcaster Maddie Pellman on leveraging the power of story to connect people with their public lands—to name a few. Despite the arid locale, the temperate rainforest that is Great Smoky Mountains National Park got ample representation, from a panel discussion on branding and style joined by Smokies Life Marketing Coordinator Elly Wells and a presentation on iNaturalist and the Smokies Most Wanted species inventory project from Discover Life in America’s Jaimie Matzko to Smokies Life winning PLA’s Publication of the Year Award for Letters from the Smokies by Michael Aday.

But as the week wore on, I felt an increasing need for the fresh air and open spaces waiting just outside the city—and a PLA field trip on Thursday offered the perfect opportunity. Led by Jennifer Heroux of the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the group explored two national wildlife refuges in the desert surrounding Las Vegas.

At 1.6 million acres, our first stop, Desert National Wildlife Refuge, is the largest wildlife refuge outside of Alaska and bigger than Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Pisgah National Forest, and Nantahala National Forest combined. It was established in 1936 as habitat for the desert bighorn sheep, but its dramatic gradient of elevations and water access makes it suitable for several hundred other native plant and animal species too. Despite the refuge’s vast acreage, it contains only one perennial stream, Corn Creek. As with most people who travel to the refuge, we visited the section through which this rare water source travels. Even in winter, the contrast was clear between the comparatively lush vegetation crowding the creek and the sparse, sandy desert extending in all directions around it.

Next, we drove an hour and a half west to Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, the Mojave Desert’s largest remaining oasis. It’s home to 26 species found nowhere else in the world, 12 of which are listed as threatened and endangered, with more than 270 species of birds passing through each year to enjoy the abundance of its spring-fed vegetation.

At both locations, the presence of water wrought a magical transformation on the otherwise severe desert landscape. Plants, including trees and shrubs, grew densely in these comparatively wet places. In the dry land outside the oasis, competition is fierce and growth impossible for all but the most rugged survivors.

As the bus headed back to Las Vegas, I watched out the window as miles of sandy desert passed by, musing that public lands organizations like Smokies Life might take a lesson from the Mojave Desert. The dusty landscape might appear unrelenting, but beneath the surface, lifegiving water can still be found, and opportunity still exists—especially when, like the thriving oasis communities of plants and animals, you can gather together and benefit from the shared shade.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.