In August 1919, Tacoma, Washington, native Ruth Sturley accompanied Deputy Sheriff Harrison McCarter on a raid of a moonshine still in the mountain hamlet of Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Ruth, who was 23 years old, had recently arrived from her home state to serve as a teacher in the local Pi Beta Phi school.

The school began in 1912 as a service project for the Pi Beta Phi Fraternity for Women to honor the 50th anniversary of the fraternity’s founding. The Pi Phis (as they were affectionately called) were a well-educated and serious group of young women who had been steeped in the progressivism of the day.

After a tour of East Tennessee by the school selection committee, Gatlinburg was chosen as the location for the school. At the time, Gatlinburg was an isolated hamlet with many outlying homes and farms. Schooling for local children was sparse at best.

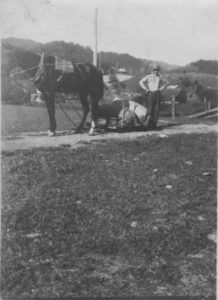

To get to their destination in Tennessee, the Pi Phis took a train to Knoxville and then boarded a smaller, slower train to Sevierville. The trip to Sevierville took most of a day, so they had to spend the night, hiring a local driver the next day to transport them the remainder of the way to Gatlinburg in a horse-drawn carriage. Roads were non-existent; the carriage driver made the trip over trails and through creeks.

When Ruth arrived in 1919 to teach at the school, she found a thriving educational enterprise. In 1914, the Pi Phis had commissioned a six-room school building, the first modern structure most people in Gatlinburg had ever seen. They had also built a teachers’ cottage. Pi Phis from across the country were encouraged to teach at the school. Some, like Ruth, stayed for one school year, while others spent a lifetime educating the children of Gatlinburg. Eventually the Pi Phis expanded their mission to include healthcare and craft marketing.

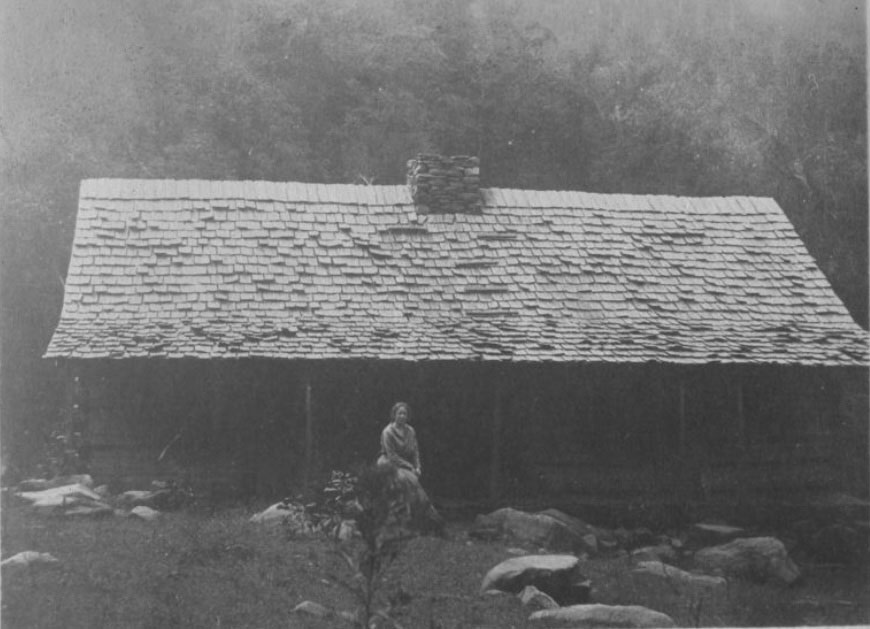

The Pi Phis were well aware that moonshine was being produced and consumed in Gatlinburg and the surrounding areas. Before teachers arrived at the school, they had to read an extensive list of books and periodical articles about “Southern mountaineers” that included mention of illegal whiskey production. The scrapbooks the Pi Phis created contain images and postcards of moonshine homes and activities. In one tragic event, a teacher conducted a funeral service for an infant of a young woman whose husband was in jail for illegal whiskey production.

Ruth recounts one lively event in letters to family and fellow Pi Phis back home in Tacoma. Harrison McCarter, handyman at the school and local deputy sheriff, arrived one Wednesday afternoon in August with a two-seated buggy pulled by Dan, the school horse. Ruth and her fellow teachers Abbie (Abby Runyan) and Emily (Burton) begged Harrison to take them for a ride.

After they started out, the conversation turned to moonshine stills. Then Harrison, Ruth wrote, “confided to us that he was going after a still about two miles off the next night.” The young women convinced Harrison to not delay but to go on the raid to shut down the still that very minute. Harrison acquiesced, suggesting they stop and pick up Mr. Creswell (probably Wilbur Creswell, manual arts teacher). The next stop was the store. Ruth reported that Harrison came back with a “huge flashlight and a bag of candy for us maidens.” Creswell added a watermelon to the snacks. Harrison and Creswell had a “mysterious conference at one side of the road,” and they were off.

While Ruth and friends ate gumdrops, Harrison made a quick side trip to Andy Huff, local businessman, who had “come along in his machine.” The party then travelled about two miles toward Sevierville before Harrison pulled over and tied Dan, the horse, to a tree. They climbed down to the river, which was quite shallow and rocky. In Ruth’s words, “We are to cross it stepping lightly from stone to stone. Well Abbie makes it beautifully—I’m in that old white dress and my white pumps and before I get across slip in neatly to my ankles. Emily also steps off—she is wearing French heels! Safely on the other side we scramble through dense underbrush along the river…”

After heading up a steep hill with thick laurel and “twigs catching at our hair and dress,” Harrison led the group through a cornfield to a little creek. They proceeded on, climbing over rocks and walking in the creek. Ruth wrote, “H. [Harrison] every little while stops—listens and peers everywhere and points out places occasionally where he says they (moonshiners) have been ‘hidin’ out’ and sure enough you can see remains of fires and flattened grass.”

The group kept on walking. Ruth’s hair, dress, and shoes were a “wreck.” She wrote, “We must have gone all of a mile up this romantically wild spot when once more H. halts us and goes forward. By this time we have had strong whiffs of whiskey and H. knows positively he’s on the trail. Yes and right ahead is a little semicircle where are several barrels and the furnace. The still itself however is gone. H. whispers all this to us and that no doubt it’s hidden somewhere nearby.”

A little disappointed, the party headed back to Dan and the buggy to eat watermelon. Ruth later wrote, “No doubt things turned out for the best—as sometimes there’s shooting and it’s risky…”

When the young women, very dirty and disheveled, finally made it back to the school, lead teacher Evelyn Bishop was waiting for them. “She thought it was a wonderful adventure but also thought we ought not to go again as it didn’t look well for the school nor was it very safe.” So ended Ruth’s and her fellow teachers’ moonshine escapades.

Without a doubt, Deputy Harrison knew that the still had been removed from the site, eliminating most of the danger to the young women. Perhaps the secret discussions he had with Huff and Creswell were to confirm that was the case. He would have been unlikely to jeopardize his position at the school by exposing teachers to a real raid. Despite the ruined clothes, the teachers had an exciting time and a story to tell their friends and family.

As for Ruth, after her year in Gatlinburg, she returned to Tacoma to live with her family. She taught school there for many years, apparently never marrying or having children. But she left behind a cache of lively letters and a scrapbook about her time in Gatlinburg, an experience of a lifetime for a young woman who grew up so many miles away.

To read more about the Pi Beta Phis in Gatlinburg and to see Ruth’s letters and scrapbook, visit https://databases.lib.utk.edu/arrowmont/.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.