When Claire Stovall applied to the Artist-in-Residence program at Great Smoky Mountains National Park, she hoped to use the time to work on the wildlife textile collages she had highlighted in her application. Then she told her family she’d been selected for the program—and that plan spun on a swivel.

“My grandmother and great-uncle both said, ‘Do you know about Dutch Roth?’” she recalled.

Stovall, 24, had never heard that name before, though she figured he had to be some distant relation—Roth was her grandmother’s maiden name. She was surprised to learn that Albert Gordon “Dutch” Roth, her great-grandfather’s cousin, is a well-known figure in the history of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, considered instrumental in documenting these rugged mountains prior to the park’s creation.

“Roth, along with his hiking partners Jim Thompson and Carlos Campbell, explored and photographed almost all of the area’s backcountry in the runup to the establishment of the park and provided people with a glimpse of what would be lost without the herculean task of conserving the area for future generations,” said Smokies Librarian-Archivist Michael Aday.

More than 5,000 of Roth’s images remain preserved at the University of Tennessee archives, and Great Smoky Mountains National Park holds about 100 more. However, Roth was never a professional photographer—the Knoxville father of two spent his career as a pipefitter for the Southern Railway. But the mountains were his passion. A founding member of the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club, Roth was an avid hiker and amateur photographer.

“I had no idea I had this connection prior to applying, so it was really quite a magical series of events that just happened to get put together,” Stovall said.

Stovall is used to stitching pieces of happenstance into something beautiful. Her current artistic focus, textile collages made using camouflage patterns, began after she finished her master’s in consumer and design science and started designing clothing for Realtree, a hunting and camouflage brand. She noticed that most of the fabric swatches her office received ended up getting thrown away.

“My first camouflage collage was just me thinking about how I could use these fabrics in a creative manner to make something for my office,” she said. She ended up with a fabric portrait of a tom turkey and a passion for the puzzle-like process.

Stovall arrived in the Smokies with a new kind of puzzle to solve. Though she grew up just north of Atlanta in Roswell, Georgia, she had never been to the park before. To orient herself to the geography of her family history, she visited Aday at the Collections Preservation Center in Townsend. He pulled up all the Dutch Roth photos the park has in its archives, and Stovall found herself inspired by the images—and by how diligently Roth had documented the location of each shot in neat cursive writing.

“I thought, ‘I can find all these places,’” she said.

This realization reformed the focus of her month in the park. Instead of working on her textile collages, she sought to replicate as many of Roth’s photos as possible. Aday pulled up a collection of old maps for her to reference, and Stovall became a regular at the park’s backcountry office, embarking on a “crazy scavenger hunt” during which she hiked almost 300 miles to remake 35 of Roth’s nearly 100-year-old photos.

The process gave her a deep appreciation for her ancestor’s stamina and backcountry prowess.

“One of the things that he was known for was images that were difficult to get,” Stovall said. “They claim he used to climb trees or go up on crazy rocks, and the cameras back then were really heavy, so it wasn’t something that was typical for a photographer to be doing.”

During his lifetime, Roth made frequent appearances in the pages of the Knoxville News-Sentinel, and even a cursory glance at these stories reveals that he was a man full of energy and good cheer.

Roth was present on the October 1924 hike to the top of Mount Le Conte that led to the founding of the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club, and he led the first official hike after the club was formed. Despite the “hard nature” of his work as a pipefitter, he summitted Le Conte 20 more times over the next three years, the Knoxville News-Sentinel reported in its Sunday morning issue September 4, 1927. In fact, by that date Roth had reached every other high point in the Smokies except Mount Guyot, climbing many of them multiple times; the story’s headline declared him “champion of Smoky Mountain hikers.”

Meanwhile, Roth’s “habit of photoplay” resulted in “one of the best collections of amateur pictures of the Smokies yet seen.” The paper quoted one-time SMHC president Brockway Crouch who said Roth’s “genial spirit is an inspiration to the other hikers,” and “not only does he carry the heaviest load of all, but he always seems ready to help others.”

Though Stovall didn’t shimmy up trees like Roth was known to do, she tried to frame her shots as identically to his as possible. Sometimes, this was easy—a view of a particular peak or landform is simple enough to replicate if you’re standing at the right overlook. But other images were more challenging, especially those showing a stretch of trail that could have been any section of the multi-mile path.

“There were a few times where I walked back and forth for 20 or 30 minutes knowing it’s somewhere right around here,” she said. “Then I’d just make my best guesstimate or suddenly be like, there it is.”

Placed side by side, the images show how much has changed in the past century. In many places, the forest is older and more grown up than it was in Roth’s day, when logging companies were still active on the land that now forms the park. When she hiked to a place called Parsons Bald to replicate a photo Roth had taken overlooking Gregory Bald, Stovall was surprised to find a thick stand of trees where her ancestor once had a clear view.

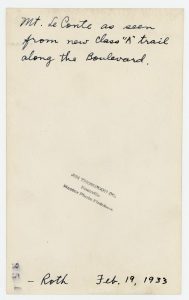

However, the trail names and routes were, for the most part, still the same, though their conditions have shifted over the years. On the back of a photo taken February 19, 1933, Roth had termed Boulevard Trail a “new Class ‘A’ trail”—at more than 90 years old, the trail is certainly no longer new, though it remains an immensely popular way to summit Mount Le Conte. Roadwork also proved a timeless presence in the mountains.

“There was an interesting Appalachian Trail crossing at Cheoah Bald and Stecoah,” Stovall said, mentioning a location south of the park’s western portion. “It was under construction then, and Dutch has a photo of it where he was crossing it. Within the last few months, they actually just started building a new crossing there, so he has pictures of the construction in 1927 and now I have pictures of the construction in 2025 at that exact same crossing.”

Stovall left the Smokies with a desire to continue telling her family’s story and plans to work with her grandmother, a photographer; her great-uncle, a newspaper editor; and her great-aunt, a genealogy enthusiast, to write a book about Roth’s legacy. She feels the pull of family, which perhaps is why during her residency she so enjoyed spending time in Gatlinburg’s Glades Road art district when she wasn’t hiking. Many of these artists continue to perfect the same crafts their grandparents once practiced.

“It’s just a beautiful connection that I think gets lost in today’s world,” she said. “It’s really cool to see that, and to see the knowledge of the crafts being passed down through the generations. It’s nice to be able to pay homage to what Roth did.”

Each year between June and November, Great Smoky Mountains National Park hosts artists in residence who spend time developing their own work as well as leading public outreach events. Park partner Friends of the Smokies funds the program. Check the park calendar for events. Visit Stovall’s website to learn more about her work.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.