Exploring the trails along Roaring Fork Motor Nature Trail one fine August day during our latest stint as this year’s Steve Kemp Writer and Illustrator in Residence brought the usual feast of Smokies sensations—the music of the rushing creek, the rich organic scent of the forest, sunlight here and there reaching down through the varied green canopy to dapple the forest floor. I fancied this all added a spring to our step, but the spring might well have come from the trails themselves, cushioned with mosses and litter.

Litter? No, not that kind—just about any trail in the Smokies is adorned with leaf litter, otherwise known as forest litter or duff—the potpourri of plant debris underfoot, things like decayed brown leaves, spent catkins, faded petals, bits of twig, and dried husks. The brown medley that is leaf litter is worthy of an essay in itself, considering its critical role in forest nutrient cycling, water retention, and as home and sustenance to myriad fungi and microarthropods. But our eye was drawn to all that was decidedly not brown in that potpourri: a surprising quantity of green leaves.

This is called greenfall by ecologists, a descriptive if unimaginative term for the green leaves and leaf bits carpeting the forest floor. The casual observer might reasonably suppose all that green leaf debris results from storms or are byproducts of forest creatures like squirrels messily feeding in the canopy. These do account for some greenfall, but most in fact is the calling card of a very different kind of forest creature: caterpillars.

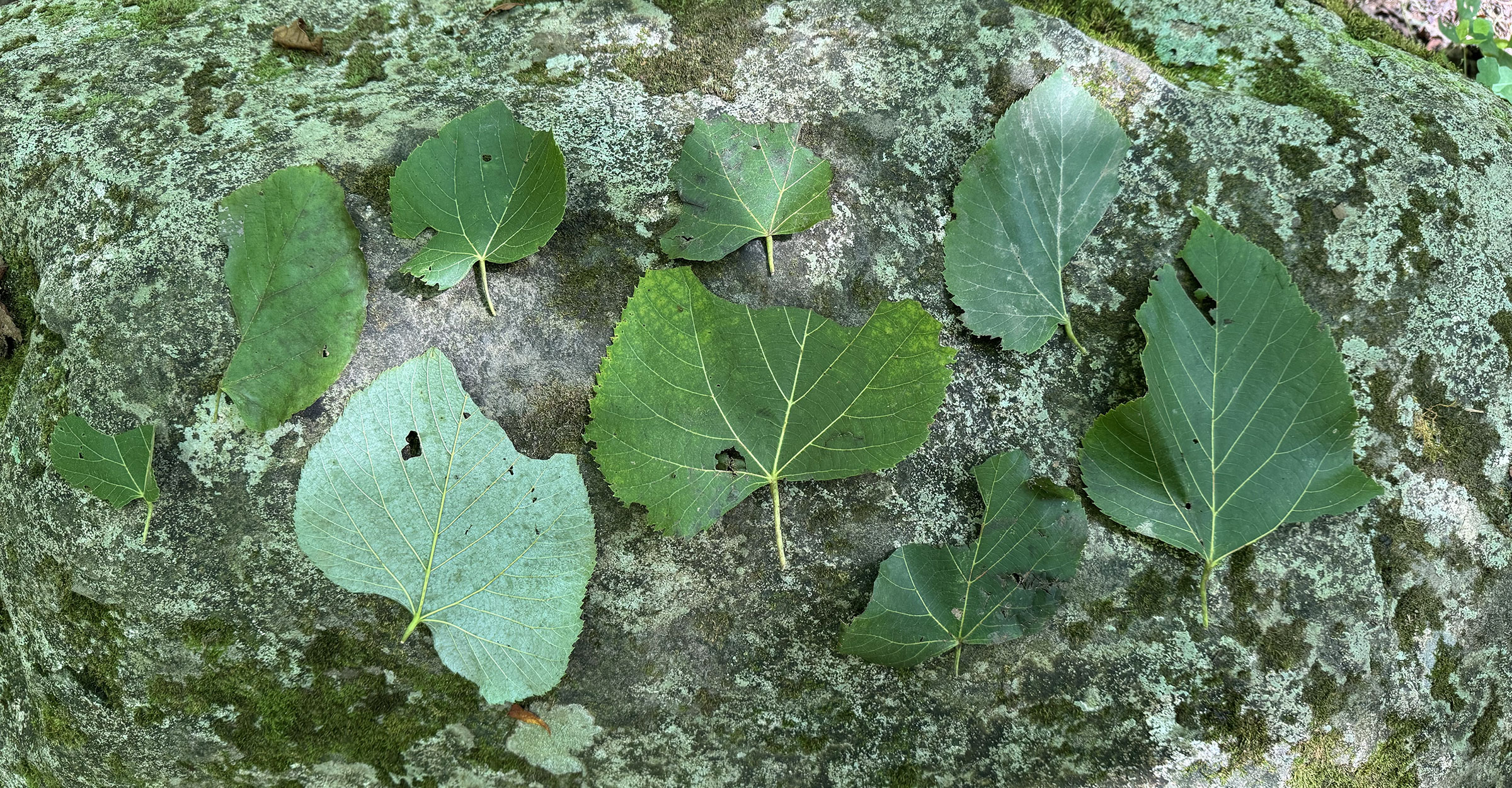

Look closely at the green leaves on the ground. You’ll notice that many are partially eaten, often a particular part of the leaf, and the leaf stem (petiole) is not snapped off at the base but shows signs of being chewed through. These are the tell-tale signs of leaf-clipping caterpillars in the canopy. Lots of forest caterpillars turn out to be leaf-clippers, partially consuming leaves and then chewing through the leaf’s petiole to send the remnant sailing to the forest floor. A quick census of greenfall along Roaring Fork reveals a pattern: leaves of a given tree species are often chewed in similar ways, suggesting, first, that each tree species has a particular species of caterpillar feeding on it, and second, that the different caterpillar species have different feeding styles. Some leaves have just their right or left side cleanly eaten to the midrib before being clipped, others have a quadrant polished off, and still others have a chunk of the leaf missing from its uppermost end or lobe.

What’s going on? Why clip leaves, and only partially eaten ones at that? Why don’t these caterpillars simply finish off the leaf, clean their plates so to speak, instead of wasting half or more of the leaf and then taking the time and energy to chew through the petiole? The precise reason is still not known, but it is thought that by clipping, the caterpillars may be either doing away with the tell-tale evidence of their presence, or somehow short-circuiting plant defenses. The hiding-the-evidence idea was first suggested some 40 years ago by the distinguished ecologist Bernd Heinrich and colleagues, in a paper that described this behavior as a kind of game of hide-and-seek with birds, albeit a game with high stakes: it is well known that birds very much depend on protein- and lipid-rich caterpillars to feed their nestlings, even birds that are otherwise mainly seed and fruit eaters. In their relentless hunt for food, birds have learned to recognize caterpillar leaf-feeding damage and search intensively on and around those leaves for prey. The caterpillars responded, evolutionarily, with adaptations of their own: green body color for camouflage, hiding out in leaf rolls or ties, and/or leaf-clipping to do away with the feeding damage. In support of the bird-avoidance hypothesis, Henrich pointed out that brightly colored, hairy, and spiny caterpillars—which tend to be toxic or otherwise distasteful to birds—also tend not to clip leaves. They instead rely on their bodily defenses to protect them if spotted, and sporting bright coloration helps them advertise that fact.

The plant-defense short-circuit idea may have some validity too. Plants can manufacture and move nasty-tasting chemical compounds in response to leaf-chewing, and this may be why caterpillars often don’t eat the entire leaves to begin with—the tastiness and nutritional value declines as the leaf is eaten, maybe reaching a point where the leaf is just so toxic or unpalatable that the caterpillar can’t or won’t finish it…but then has to deal with the prospect of the partially chewed leaf attracting the unwanted attention of caterpillar-hunting birds. Clipping the leaf may not only help the caterpillars hide but also remove damaged leaves that, if left in place, might result in the plant mobilizing chemical defenses to adjacent leaves—or the whole branch—rendering that part of the tree inaccessible to caterpillars.

Whatever the reason, it’s clear that there is much more to greenfall than meets the eye! Pause on your next late-summer hike to check out those green leaves littering the ground. Take a closer look to discern the feeding pattern on leaves of different species—oaks, sourwood, tulip poplar, dogwood, maples, basswood, and more—and see how their petioles are cut partway down from the leaf, not separated from the tree at the petiole base like shed autumn leaves. Now look up at the green ocean of canopy above, and know that here, there, everywhere are well-hidden caterpillars lying low on leaves or twigs, hoping hungry birds don’t notice them or the stumpy petiole stems nearby marking the presence of leaves that were.

What you’re seeing is evidence of an age-old drama between trees, caterpillars, and birds—one of myriad examples of ecological interconnectedness in the Smokies and beyond!

Reference: Bernd Heinrich & Scott L. Collins. 1983. “Caterpillar leaf damage, and the game of hide-and-seek with birds.” Ecology 64(3): 592–602.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.