A certain purposeful optimism marks the first day of a long hike, when obligations, distractions, news, and civilization are long gone. What a relief to shed the monotony and replace it with fresh air.

This hike, starting on a Friday at the end of summer on a section of the Appalachian Trail in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, seemed the right one for many reasons. Years ago, my aspirations to embark on a “big adventure” took root after reading too many books by outdoorsy types who took some great leap into the unknown, searching for excitement in nature. Their tendencies, like mine, were to naively dismiss how harsh the elements could be.

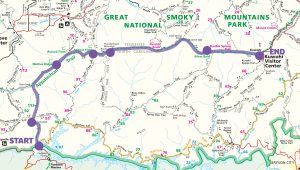

I’m not a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants person. Overthinking, prepping, and worrying are my good buddies. So, the AT trek from Fontana Dam to Kuwohi over an extended Labor Day weekend wasn’t concocted out of sheer misguided energy. Foresight, YouTube videos, maps, proper gear/food assemblage, pre-hikes, daily exercise, and excited anticipation preceded it. I understood the parameters: four days in the Smokies backcountry on single track over hard dirt, mud, roots, overgrowth, poison ivy, rocks, and jagged stones, all essential elements of the “experience.” This was the AT, mind you, and the challenge was in the enduring.

My goal, besides marking my 50-ish birthday, was to replicate a tiny sliver of the full AT hike that thousands of optimists try to scratch off their bucket lists each year. Since I’d only be trekking a 30-or-so-mile stretch of the 2,200-mile trail, the difficulty factor had to be less—much less, far-far less, a blip-on-the-screen less—making it doable, enjoyable, and unforgettably satisfying. Did I mention being naively dismissive of reality?

The first crack in my confidence came the night before the hike, when a respected colleague, a far-more experienced hiker than me, laughed and tossed me a sly smile after he brought up the first milestone of the hike—Shuckstack. Would I be going to the fire tower? Actually, the side trip seemed skippable, since the tower added mileage onto the longest day of the trek, already almost ten miles, and the tower might be roped off to climbers. So, no, I probably wasn’t. Regardless, his telling headshake spoke volumes, a nice way of conveying, “You’re in for it, sister.”

The next morning, perhaps halfway to the tower spur, all uphill, Miley Cyrus’ “The Climb” started to creep into my brain, and not in a nice way. Pfft, what did she know about climbing a real mountain? Discernable progress felt nil, except for my progressively aching feet. More concerning was the recent memory from two hours prior of standing on Fontana Dam and looking toward the distant peak where the tower perched, an indistinguishable speck. And the tower site was only a third of the way to the night’s final destination, Mollies Ridge.

My companion, a practical, safety-minded, strong climber carrying a much heavier load on his back, was talking non-stop. Good, in a sense, to buffer the crushing inclines. We ran into three much younger men probably half our ages, also backpacking and also fatigued, and we shared our prospects. We were all headed to the shelter at Mollies Ridge, but at that point, us “old folks” wouldn’t be anywhere near it by nightfall. They felt equally dejected. We both ended up at Shuckstack separately, a jaunt we made mostly due to lack of signage. Fortunately, the tower stairs were clear to climb. After peering off the frighteningly high tower, we left and never ran into the youthful trio again, one of whom was carrying his friend’s backpack.

Let me stop here and admit that the elevation gain hadn’t given me much pause during planning. I’d failed to register we were climbing more than 2,500 feet in elevation on Day One. I’d even quipped to my 85-year-old mother before leaving, “It’s easier to hike uphill than down,” which is true for my knees, but in this case was a shameful oversight. Day One had us scaling the height of a 250-story building while wearing unknown pounds of gear. We hadn’t weighed them, partly because we didn’t want to know.

With twilight bearing down, my feet felt like nubs and my rock-solid hiking partner hit a wall, energy spent. Even with a map, we had little sense of how close we were to the shelter. All we could do was push ahead, one knee-lift at a time. My thoughts turned fatalistic: “I still have three more days of this. My feet will be permanently ruined. Who does this for fun?”

When we finally pulled out of the foliage to Mollies Ridge, relief hit us like a cool gust of air. A smiling young man from Georgia who’d passed us earlier in the day sat on a bench beside the shelter as if he’d been waiting and cheerily said, “I thought y’all weren’t gonna make it.” We had dinner with him, heard his backstory, had a few laughs, and fell with a thud onto our inflatable mats for the night in a tent we’d pitched just before dark.

Don’t look at the map, my hiking companion kept advising me. In a sense, he was right. The reality of the map was destructive. At 3 p.m. on Day Two, miles of uphill to go, I mentally quit, sat on the edge of a log, and lamented that I’d bitten off more than I could chew, flailing the map in one hand. With as cool a head as I could muster, I flatly told my hiking partner that we needed to get off the trail and find an alternate route to civilization, sparing our bodies the torture of the relentless roller coaster in the woods.

I believed we’d never physically be able to reach Kuwohi, still such an unbearably long dotted line away. The climbs and pain in my feet had destroyed my resolve. He folded the map and returned it to his pack like a parent gently removing a fought-over toy. I wanted to toss my extra clothes and sleeping bag into the forest and rid myself of the weight. He would have grabbed my wind-up-to-the-pitch, had I actually followed through on my threat. Instead, he took some of my load. Afterward, my feet felt slightly less angry.

Guidebooks can provide the skinny on logistics, but they generally don’t convey the internal journey required for an outdoor challenge. Even “strenuous” doesn’t convey the gravity of a hike like this one. Here, in the backcountry, help is limited, and disastrous hazards and injuries are a misstep away. The ability to stay the course is an individual decision made by sheer will and fortitude. The AT is an island of your own choosing. Forward motion is the only way off.

We arrived at Spence Field before 5 p.m., ate instant soup but pined for hamburgers, and had a quiet night away from other overnighters. Feeling our age, we talked about adventures we’d had as our younger selves. The next morning, we broke camp at dawn and literally dashed out, determined to get miles behind us.

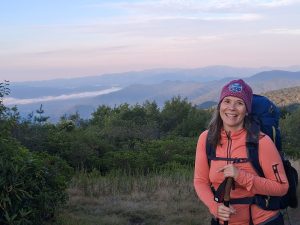

That chilly morning, we crested Rocky Top, a beautiful rock outcrop on the AT with stunning views. Here, under blue skies, I celebrated my birthday. Arriving there on my day was an unplanned fluke of incredible fortune. The dramatic vista was an unexpected gift. We ate instant oatmeal and drank creamy hot chocolate and instant coffee, supplemented with cream from a can, our one indulgence. It was the best meal of the hike. Maybe the best moment.

I wish I could say the rest was easy. We didn’t end Day Three until 9:30 p.m. I resorted to singing show tunes from Fiddler on the Roof, The Sound of Music, Grease, and Cats to take my mind off each painful step. Yet around me, the forest oozed beauty. Morning mist, vibrant green moss beds, boulders of unusual size, tunnels of rhododendron, indescribable lichen and mushrooms, scores of butterflies, elaborate spiderwebs, a passing deer.

But the necessity to concentrate on each step diminished my awe. At one point, I shouted into the forest, “Who the [unladylike adjective] thought this trail was a good idea?” George Masa and Horace Kephart became my anti-heroes. Then it started raining. I envisioned myself as the landlocked version of Lieutenant Dan in Forest Gump, fist-pumping heaven from the mast of a shrimp boat. Luckily, the rain was light, the temperature tolerable, and the path didn’t turn into mud.

As sunset arrived on our last night, my companion flinched at a rustle in the nearby waist-high foliage. Bear in the underbrush. “Get in front,” he demanded, shaking me out of my straggling to close our pack for safety. Though we’d spent hours trudging, I doubled my pace. It must have been adrenaline because the pain in my feet vanished. We snapped on our headlamps. I worried about slipping but wanted to run. We pushed another hour to reach a shelter closer to Kuwohi. When we arrived at Silers Bald, I couldn’t sleep because of the cardio buzz.

Lots hurt too—my hip, my feet, my arm from a minor fall earlier in the hike. Day Four was dawning, and I knew I’d never be there again. We were five miles from the finish line.

The trek ended in the parking lot of Kuwohi at 12:30 p.m. on Labor Day at ~6,600 feet, three-and-a-half days and 33 miles from the start. I can’t say a wave of euphoria or pride hit me right then. It took a hot meal, a warm bath, and a couple of hours until a sense of accomplishment and relief settled in. I’m immeasurably grateful I finished.

More than 70 miles of the AT runs through Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Contact or visit the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Backcountry Information Office, 865.436.1297, for permits and information about backcountry hikes. Also, check out our guidebook Day Hikes of the Smokies for ideas about single-day excursions in the park.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.