In October 2019, Rhiannon Skye Tafoya was a year out of her master’s program and excited to begin an art residency at the Women’s Studio Workshop in Rosendale, New York. Tafoya, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and Santa Clara Pueblo, planned to use her time there to create an artist book.

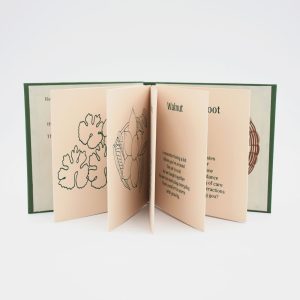

Her vision would mimic a basket design and honor her maternal grandmother, Martha Reed-Bark, who was an EBCI member and accomplished basketmaker. But shortly after she arrived in Rosendale, Tafoya discovered she was pregnant—and that changed everything.

“I started making it differently,” she said. The book’s design shifted, and so did the poetry that sits inside the basket it forms.

“The writing was very heavy toward lineage and seeing my granny and figuring out, ‘How do I pass on her values to my kid to make sure that they’re a Cherokee-strong person too?’” Tafoya said. “That book almost felt like it was gifted to me from my granny.”

It was a gift that transformed Tafoya’s career. Tafoya, 36, had been printmaking for years before she created Ul’nigid’—Cherokee for “strength”—but “nothing was sticking.” Every month, she struggled to keep making art while still covering her basic needs. Ul’nigid’ didn’t sell well at first, but once the initial panic of COVID-19 subsided, “everyone just started buying it,” including, in 2022, the Museum of the Cherokee People on the EBCI’s Qualla Boundary. For the first time in a long time, Tafoya’s finances felt stable.

“It’s been a really good journey since 2019,” she said.

Art is central to Tafoya’s earliest memories, her artistic development continually encouraged and inspired by her family and the land that birthed them all. Artistry ran in the family; her grandmother, father, brother, and cousins all had their own artistic endeavors, ranging from painting and drawing to woodcarving and pottery.

But when she was young, Tafoya never saw art as her future. A runner on her high school’s cross-country team, she planned on a career in sports medicine. However, shortly after starting college she discovered that science was not her strong suit. She failed out of the program and changed schools, and that’s when she got interested in painting. Tafoya took her newfound passion to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she found a discipline that enthralls her still—printmaking.

“There’s so much to investigate,” she said. “There’s always layers. There’s always textures. There’s colors. There’s just a vast amount of ways to make a print.”

But for several years after graduating from art school, Tafoya wasn’t making art at all. She was “just trying to figure out how to make a living.” She began working retail for Nike and later moved to Portland, Oregon, hoping to embark on a design career with the company.

“It didn’t work out, and thankfully it didn’t,” she said.

Instead, she enrolled in the master of fine arts program at Pacific Northwest College of Art, earning a print media degree in 2018. In addition to honing her printmaking and book-art skills, the program introduced her to letterpress printing. She’d never known about that medium before, but now it’s the biggest part of her practice.

“Everything is so intricate in the whole process,” she said. “You have to learn it in order to do it, and that’s what’s beautiful about it. There’s always that connection of learning from someone and then teaching someone else, and the same with basketry. That’s how you make baskets. You have to know your materials before you can actually make something.”

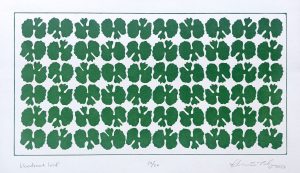

Basketmaking is intrinsic to Cherokee culture, and to many other Native cultures throughout North America. Each tribe has its own traditions, its own process, its own materials. And the basket—the artistry of it, the usefulness of it, the heritage of it—represents something special to Tafoya.

“I like that there’s a history that’s within it, the way that cutting a tree isn’t just to cut a tree,” she said. “There’s so much knowledge in understanding why that tree is going to make a good basket.”

In this way, Tafoya sees parallels between the basketmaking process in her work as a printmaker and paper weaver.

“I’ve been thinking about paper weaving as an analogy for the past couple years,” she said, pondering how the process of working in different print shops and using the unique metal ornaments available at each is similar to the way a basketmaker must visit a specific landscape to gather materials for weaving or dyeing. The selection of paper and ink is akin to dyeing. Then, like a basketmaker does, she takes all her materials home and begins to process them, cutting them to size and weaving them together.

In every piece Tafoya creates, her Cherokee culture—and the Great Smoky Mountains region where it flourishes—shines through. But it’s a fine line, she says, between expressing her cultural identity and exploiting it. She works hard to stay on the right side of that divide. Tafoya has been learning about basketry for more than three years now, and last fall she embarked on a formal apprenticeship funded by a North Carolina Arts Council grant. Though the grant has been completed, the mentorship will continue for as long as possible.

Tafoya’s prints and weavings are so heavily influenced by basket motifs that she would “feel like a fraud” if she wasn’t making baskets at the same time. But unlike her contemporary art, the baskets are not for sale. Her grandmother earned her living through basketry, and few of her pieces remain with the family—a point of sadness for Tafoya.

“My baskets are only going to be gifts,” she said. “They’re only going to be within my family, so that no one’s looking for my baskets later on in life and cannot find them.”

These days, Tafoya is staying busy with a bevy of contemporary art projects. In June, she completed her second artist book for Women’s Studio Workshop, Relational Sentience, about her relationship to four specific natural dyes. A LIFT award from Native Arts + Cultures Foundation will fund creation of a third book, to be completed by August 2026.

This fall, Tafoya did a two-person show at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center and a solo show at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Tennessee, where she also curated a show. Over the summer, she completed an artist fellowship and residency at Forge Project in New York and taught a weeklong class at Shakerag Workshops in Sewanee, Tennessee.

Between her apprenticeship and her flourishing contemporary art career, Tafoya stays busy. But perhaps her most important role, she said, is as a wife and mother. Her son, Otis, now five, fueled the creative muse that made her first book so successful, and in a way she’s indebted to him for the career she now has. But with success comes sacrifice. She completed nine different artist residencies in 2022 and 2023 in locations ranging from Marshall, North Carolina, to Halden, Norway. All that travel was “really, really hard” for the entire family, and she made a commitment to stay home much more in 2024 and 2025.

But that independence is also what Tafoya loves about life as an artist. She cherishes “having the freedom to do what I want, when I want, not having to answer to anybody,” and she does her best work in her home studio, up a little-traveled road in Cherokee’s Wolftown community, nestled at the foot of the Plott Balsam Mountains.

“I’m always looking for the next opportunity,” she said.

Learn more about Tafoya and how to purchase her work at SkyeTafoya.com. An earlier version of this story was originally published in the spring 2025 issue of Smokies Life Journal, a twice-yearly magazine that is the primary benefit of joining Smokies Life. To read more stories like this while supporting Great Smoky Mountains National Park, visit SmokiesLife.org/Membership and become a Park Keeper.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.