On January 15, 1919, the Knoxville Sentinel’s headline read “Nation To Be Voted Dry Within Twenty-Four Hours.” Dry was the shorthand term for a ban on alcohol, commonly referred to as Prohibition. For Prohibition to become law, three-quarters of the states first had to pass the 18th Amendment to the Constitution. That threshold was indeed reached the next day. The amendment provided that, one year from ratification, it would be illegal to manufacture, sell, or transport intoxicating liquors in the United States. It also gave Congress the power to pass laws to enforce the ban.

In 1919, as a follow-up to the 18th Amendment, Congress passed the Volstead Act, named for Andrew Volstead, the chair of the House Judiciary Committee and a strong Prohibition proponent. President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the act, but his veto was overridden, removing the last barrier to Prohibition. The act made it illegal to “manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish or possess” any beverage that contained more than one half of a percent alcohol.

The road to Prohibition

The 18th Amendment and The Volstead Act were the culmination of decades of efforts by organizations including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League to eliminate alcohol consumption in the United States. It was a movement supported by women who had witnessed husbands and fathers spend their income on alcoholic beverages, leaving little to support their families. Many Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist churches campaigned for the elimination of alcoholic beverages for similar reasons. Factory owners who wanted sober and alert workers also supported temperance.

The states of Tennessee and North Carolina had seen efforts to reduce the consumption of alcoholic beverages throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Before the passage of the Volstead Act, states had been free to regulate alcohol independently. Temperance efforts in Tennessee included a Four-Mile Law, first passed in 1824, prohibiting alcohol sales near churches. The law was later expanded in 1887 to prohibit alcohol sales within four miles of any country school. Subsequent laws created dry or alcohol-free towns, cities, and counties throughout the state. Some remain dry to this day. When the time came for a vote on the 18th Amendment, the Tennessee General Assembly overwhelmingly gave its approval.

North Carolinians advocated for Prohibition through local organizations including the Asheville Temperance Society and chapters of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League. In 1881, a statewide referendum on Prohibition was defeated. Undeterred, Prohibitionists took the fight to local communities. Over the next 20 years, several rural areas and small towns became dry through referendums. Subsequent state laws eroded the sale of liquor by outlawing rural distilleries and eliminating sales of alcohol in towns with populations under 1,000. In 1909, a statewide referendum on Prohibition succeeded, and North Carolina became the first state to outlaw liquor by a direct vote of the population, ten years before Prohibition became the rule of law in the entire United States.

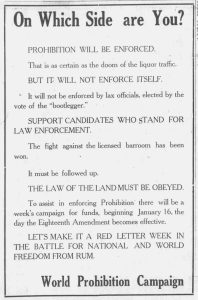

In preparation for implementing the Volstead Act, the Chattanooga News reported that the Internal Revenue Service, charged with enforcing alcohol regulations, would have 3,000 agents assigned by zones across the United States. The IRS already had 2,283 agents. This added only 800 new agents for the entire country. The agents were to work with local police to carry out enforcement activities. Although most of the illicit distilling had traditionally occurred in the Southern Appalachians, the plan was to focus on cities where the demand would be highest and illegal activities most prohibitable.

In the early years of Prohibition, consumption of alcohol did drop and arrests for drunkenness fell. But Congress never appropriated enough money to properly enforce the law. Federal agents were not able to shut down illegal alcohol production in the Southern Appalachians before Prohibition when the demand was primarily local. With Prohibition in place, the demand became exponentially greater.

Within a short period of time, the illegal production and distribution of liquor, called bootlegging, became rampant across the United States. Organized crime syndicates became common, fueled by sales of illegal alcohol. An era of corruption and lawlessness had begun.

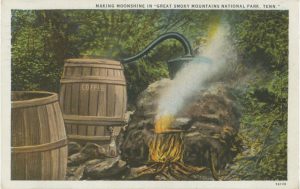

Prohibition in the Great Smokies

How did nationwide Prohibition affect the moonshiners in the Great Smokies and surrounding regions who had been making illegal alcohol for over 100 years? Initially, not much changed for the moonshiner in the Smokies and adjacent communities. Soon, however, the increased demand for spirits reached the Smokies. As Dan Pierce explained in his book Corn From a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains (2013, Smokies Life), in the past moonshine might have been delivered only to local towns, but “in the 1920s and ’30s illegal liquor flowed out of the Smokies to cities across the nation.” The advent of better roads suited for automobiles and manufacture of faster, larger cars aided in the transport of spirits to faraway locales.

According to a 1922 article in the New York Herald and syndicated in other newspapers, criminals who committed crimes elsewhere relocated to the Smokies and other parts of the Southern Appalachians to take up moonshining. For these desperate men, the Smokies had the advantage of being located in two states. If the local authorities in Tennessee were after a moonshiner, he had only to slip across the mountains to North Carolina where Tennessee officers could not pursue him. Of course, the reverse was also true.

Pierce explained that the demand for moonshine allowed blockaders, as the new moonshiners were called, to expand production with new methods and technologies. An increase in demand fueled the creation of larger and more efficient stills. While some blockaders turned to steam stills, most Smokies moonshiners favored huge pot stills with the ability to ferment the mash right in the pot itself, saving time and money. Traditionally made of copper, this type of still was common in Cocke County, considered the center of illegal whiskey production in the Smokies.

To further boost profits, moonshiners began cutting the proof of the whiskey and masking the cut in quality with other substances. The new processes themselves introduced dangerous impurities. United States Prohibition Commissioner Roy A. Haynes, in a series of essays published in newspapers, wrote that the old-time moonshiner knew that the first and last products of the distillation process needed to be thrown away. The new moonshiner did not care about poisons or impurities in his product. The new moonshine was never properly aged in wooden barrels to remove dangerous substances. Laboratory analysis of both traditional and new moonshine showed that the new moonshine contained poisons which, taken in quantity, could result in serious injury or death. This information did little to stop the consumption of illegal spirits.

By 1922, there were still some old-timers moonshining in the Appalachian Mountains, but they tended to be older men like Ham Wilson, according to the syndicated article in the New York Herald. Wilson’s whiskey, made for his own consumption, was a point of pride with him. “He is a past master of the art of distillation, and his product meets the most exacting tests. His home is high up in the Great Smoky Mountains. . . .” But the Ham Wilsons were a dying breed. The sons of men like Wilson were “more modern.” They were into moonshining for as much money as they could make and looked with “high scorn upon the scruples of the older folks.”

Writing in Century magazine in 1929, Francis Lynde, a popular writer, bemoaned the changes in moonshine production and distribution brought about by Prohibition. Despite ignoring revenue laws, the whiskey producers before Prohibition were generally law-abiding local people who were producing moonshine to use surplus corn and earn a little money. The whiskey produced in the “older day” was “pure and free from drugs. As a beverage it was unique; and as an intoxicant, at least for the outlander, it was a profound success.”

Lynde went on to say that after Prohibition became the law, the job of the moonshiner was taken over by hired men, paid by bootleg syndicates. When a still was raided, the employees were seldom apprehended. The bootleggers had an extensive spy system in place to warn the still operators that a raid was imminent. An untended still was destroyed by the officers, but this did not deter the bootleggers. A new still in another location was quickly erected.

As illegal whiskey distilling became a big business, corn production in the mountain regions increased as did the sales of fruit jars, copper, and other still components. According to the article in the New York Herald, “It is a fact that mountaineers, talking over affairs with each other, invariably predict crop prospects in units of gallons rather than bushels.”

As the 1920s progressed, it became clear that Prohibition, the national experiment in social control, was a failure. For many, the lure of alcohol was worth breaking the law. The corruption of politicians, business leaders, and entire police departments had become rampant across the nation. On December 5, 1933, the 18th Amendment was repealed by the passage of the 21st Amendment. Only North and South Carolina rejected the amendment, although several states did not vote once the three-fourths majority of states had indicated approval. The 21st Amendment returned control of liquor laws back to the states, where it remains today, fostering a patchwork of local and state laws regulating alcohol production and sales.

With the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, much of the land that had been available to moonshiners became off-limits as many families were removed from their farms. By 1931, park lands were controlled by rangers who aggressively removed stills that they encountered. Although the national demand for illegal alcohol waned with the passage of 21st Amendment, demand in dry Tennessee and North Carolina counties and towns remained, creating a smaller but significant market for illegal whiskey produced in areas surrounding the Smokies.

For more information, see Daniel S. Pierce’s Corn From a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains (Smokies Life, 2013). Anne Bridges is compiling a book of her essays on moonshining for Smokies Life.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.