Every year, the Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center in Great Smoky Mountains National Park welcomes hundreds of young people to immerse themselves in the scientific wonders of America’s most biodiverse national park. A new installation invites them and other visitors to embrace the park’s poetic wonders as well.

US Poet Laureate Ada Limón unveiled the piece—a wheelchair-accessible picnic table inscribed with Lucille Clifton’s poem “the earth is a living thing,” plus an invitation for readers to create their own response to the surrounding landscape—on Saturday, July 20, during a tri-lingual program at Oconaluftee Visitor Center. The visit was the fifth stop on Limón’s Poetry in Parks tour, which is bringing site-specific poetry installations to seven national parks ranging from Washington’s Mount Rainier to Florida’s Everglades. It is also the first-ever partnership between the National Park Service, Library of Congress, Poetry Society of America, and a US poet laureate.

“An event like this recognizing poetry in national parks is long overdue,” Superintendent Cassius Cash told the more than 150 people gathered to witness the moment. “Poems inspire us to see beauty, build bonds, and fill the need of our souls. I believe the same is true for the Smokies.”

Limón said she was “proud” to include the Smokies’ wild yet welcoming landscape on her itinerary and felt the poem by her “poetic hero” Clifton to be an especially fitting tribute to these storied mountains.

“To me she is an iconic voice that is both timeless and deeply human,” Limón said. “I chose this poem because it speaks to the softness and tenderness of this earth and a sense that the Earth itself is a beloved creature.”

Rather than the predicted rain, a gently overcast sky spread above the tent where Limón read four of her own poems, as well as Clifton’s. Rooted in the tangible—the greening of the trees in springtime, a blue-bellied lizard sunning on a rock, the black expansiveness of space—Limón’s selections pointed toward universal themes of curiosity, heritage, and hope.

For Limón, the natural world has been a lifelong source of peace and poetic inspiration. During her childhood in northern California, the practice of naming and identifying plants and animals was part of her elementary school education, leading to an “obsession” with learning the names of each organism that has carried through to adulthood. In that recognition, she believes, lies a deeper sense of connection and communion.

Even for those who rarely venture outdoors, the metaphors of nature are difficult to escape—our minds are foggy before coffee in the morning, our thoughts cloudy when we’re stressed or tired. We weather the storm, move like a moth to a flame, appreciate relief like a breath of fresh air.

“I think that part of writing poetry is to not just look for those metaphors, but to allow yourself to receive the metaphor from nature,” Limón said in an interview with Smokies Life. “A lot of what I try to do is pay deep attention and receive the world, and then try to figure out what that attention, what that image, what those descriptions are telling me about my life. That’s something I’ve been doing ever since I was a very young writer.”

Space, then, the deliberate taking of time to breathe and to be, is essential to the practice of poetry—both to the writing of it, and the reading of it.

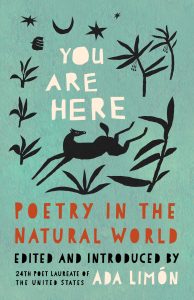

“Watching [the trees] makes me feel at once more human and less human,” Limón writes in the introduction to You Are Here, the poetry anthology she edited as the counterpart to her Poetry in Parks initiative. “I become aware that I am in a body, yes, but it is a body connected to these trees, and we are breathing together. You might not know this, but poems are like trees in this way. They let us breathe together. In each line break, caesura, and stanza, there’s a place for us to breathe.”

That principle of communal breath reverberated throughout the Saturday program. Each speaker uttered only one sentence at a time before pausing as an American Sign Language interpreter repeated the words, next followed by a Spanish language interpreter, a three-part wave of meaning.

“It’s powerful to see people came from multiple hours away to get here, because they all thought this was an important moment,” said Kimberly Smith, a citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and mentor for the Junior North American Indigenous Women’s Association. “They all understood the power of this gathering.”

Smith’s daughters, Junior NAIWA members 14-year-old Jasmine and 12-year-old Janée, helped Limón and Cash unveil the picnic table. It was a “healing” experience, Jasmine said.

“Today, it was a powerful day, because how many people showed up just to hear [Limón] speak with all the powerful words she said,” said Janée. “I just felt like that power was here, and you couldn’t turn away from it.”

Limón hopes that, in the decades to come, anyone encountering the picnic table at Purchase Knob will feel the power of Clifton’s words, and of the landscape in which they reside. And, maybe, feel inspired to write some words of their own.

“Putting these iconic poems in parks is an opportunity to give people a deeper sense of attention themselves, so they might be able to be even more present in these really beautiful, special, sacred, protected places,” she told Smokies Life.

In this world of instant notifications and knee-jerk responses, even the most present among us often have difficulty paying attention. Perhaps, by sitting at the picnic table, reading the poem, and responding to the prompt, future park visitors will experience “a deeper moment of reflection” than they do in their day-to-day lives, Limón hopes. These experiences might then lead to a reaffirmed sense of wonder and hope for the future—even in the midst of a chaotic and divided present.

“We need to think about new ways to connect to each other and to connect to our planet,” she told Smokies Life. “For me, poetry is one tool. It’s one way in, and if it brings you to the national park, if it brings you just to a moment of attention to the natural world around you, if it gives you one breath, that might be enough for right now.”

Learn more about Poetry in Parks at nps.gov/subjects/literature/poetryinparks.htm. Share your response to the landscape around you using the hash tag #youareherepoetry.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.