Editor’s note: This is the second installment of Anne Bridges’ three-part series on a Blount County outlaw known as Hut Amerine and his illegal moonshining enterprise in the Great Smoky Mountains prior to the creation of the national park. Click here to read part one.

Hoping to surprise Hut Amerine and his men, Cooper quickly organized a second raid to be led by his two sons William and John Cooper. It is doubtful that either of the Cooper sons had any law enforcement training or experience. William, who was approximately 30 at the time of the raid, is listed as a store clerk in the 1870 census. The younger son John, who was 28, was listed as a depot agent in the same census.

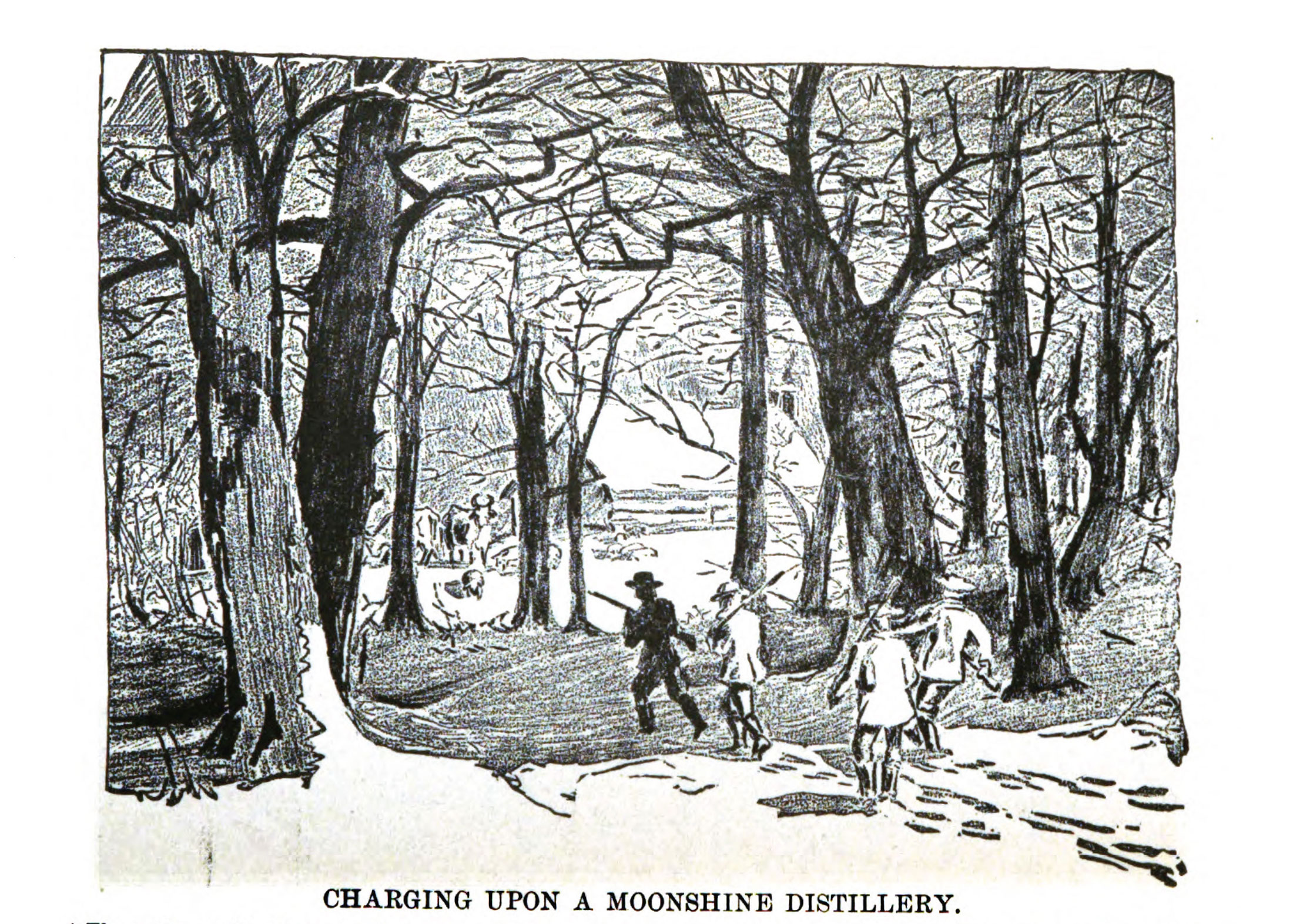

After arriving at the illegal moonshine location at dawn, the federal agents divided into four squads surrounding the distillery. But they found it dismantled. The agents then decided to split up, leaving a few men at the abandoned distillery. John Cooper and two other agents began the search for the new still location. They entered the yard of the new distillery where they were surprised by the voices of Amerine and two of his men, Adam Wilson and Fletch Emmett, ordering the agents to surrender. At first Cooper thought it was some of his friends trying to frighten him. But then Amerine, Wilson, and Emmett appeared in the early dawn light and started firing at the agents.

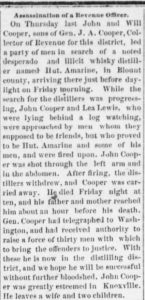

The gunfire volley was aimed at John Copper. There were several theories as to why Amerine and his men focused on Cooper. Some believed that the moonshiners thought he was the informer Davis, the man who had led the agents to the sill in the previous raid. Apparently, John Cooper resembled Davis. Others theorized that, since Amerine, Wilson, and Emmett had sworn vengeance on the Coopers, they knew exactly who they were aiming to hit. Three shots wounded Cooper—one went through his hat, another struck his left arm and his thigh. The third shot hit his abdomen and came out near his spinal column.

John Cooper exclaimed, “I’m shot,” running up the hollow and falling after a short distance. His brother William came to his aid. Amerine and his men took off and could not be located.

John Cooper was taken to a nearby house. Dr. Blankenship of Maryville and later Dr. Boynton of Knoxville came to attend to the wounded man, but the abdominal wound was fatal. Cooper died later that day.

A posse was immediately sent to arrest Amerine, Wilson, and Emmett, but they could not be found. General Cooper offered a reward of $300 for the arrest of the three men. Subsequently the governor, James D. Porter, offered an additional $200 bounty on each of the moonshiners.

The Maryville Times, a local newspaper that frequently editorialized on the evil of moonshine production and consumption, published an article in the August 14, 1878, edition decrying the murder of John Cooper. According to the editorial, men who drink liquor are those that “speak lightly of this foul murder. Liquor drinking deadens the conscience and makes men insensible to the obligations of good citizens and to the true nature of crime.” It went on to say that the murderers were outlaws who have inflicted a “life-long sorrow” on John Cooper’s family. Any good citizen should cooperate in bringing the murderers to trial.

Amerine wrote a letter to Governor Porter requesting that he withdraw the bounty, protesting his innocence. He claimed that he had four witnesses who would testify that he was at home the evening of the shooting, three quarters of a mile from the location of the assault on the agents. Amerine offered to surrender so he could stand trial to prove his innocence, providing he would not be charged with the additional federal crime of making illegal whiskey.

Amerine’s protests of innocence did not earn him a reprieve. In February 1879, Amerine and Emmett were captured and sent to jail in Knoxville.

Part three of this series describes Hut Amerine’s subsequent imprisonment in Knoxville and two daring escapes.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.