Depending on your perspective, seeing a joro spider (Trichonephila clavata) for the first time is either an enchanting experience or an alarming emergency. These creatures are strikingly beautiful, their bodies bearing an intricate pattern of black, white, and yellow, splashed with a shot of red. But they’re also strikingly large. While males stay much smaller, females can achieve a leg span of up to four inches, their bodies more than a quarter of that length.

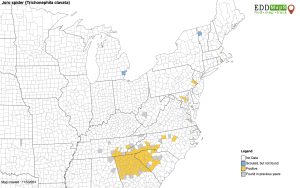

Native to Asia, joro spiders have been living in the United States since at least 2013, when they were spotted in Georgia between Athens and Atlanta. They’ve been spreading ever since, and on October 17, Great Smoky Mountains National Park recorded its first joro sighting. Jarren Rendon, an AmeriCorps intern with the park’s Vegetation Management Branch, spotted it just west of Hyatt Lane in Cades Cove as he was working to remove exotic vegetation from the area.

Park Entomologist Becky Nichols said that, while the finding was noteworthy, it was not surprising. The spider’s presence in Western North Carolina was first recorded on iNaturalist in 2021, with multiple observations in East Tennessee in 2024. An October 2023 sighting put the spider just outside the park boundary south of Fontana Lake near Bryson City, and on September 8, an iNaturalist user documented the joro spider in Townsend.

“That’s just down the road from Cades Cove, so it’s not a surprise, really, that it was found there,” said Nichols. “We’re not sure how long it’s been there, but we did expect to see them at some point in the park.”

Earlier this year, park partner Discover Life in America added the joro spider to the Smokies Most Wanted list. Park visitors who spot one of these species can upload their observations to iNaturalist and help scientists better understand their prevalence in the park.

“It’s good to have an idea of where it is in the park so that, as it’s being studied, if we do find out more information about potential harm it could do to our native species, we have a better idea of where to go if we need to work on control measures,” said Will Kuhn, director of science and research for DLiA.

Now that the spider’s presence has been verified inside the park, Nichols is considering what type of research or monitoring efforts the park should engage in as it continues to spread.

“It’s something we’ll keep our eyes on, like any of the potentially invasive species that could have impacts on the ecosystem,” she said. “And we’ll be paying close attention to studies looking at ecological impacts of this spider in order to determine if we need to take any management actions. I don’t suspect that will be the case, but we’ll just have to wait and see.”

Andy Davis, assistant research scientist at the University of Georgia’s Odum School of Ecology, has been studying the joro spider for years as it’s proliferated throughout northeastern Georgia and beyond. He said the “jury’s still out” on the spider’s potential impact to native species but that early indications are that it’s “not even in the same category” as extremely destructive invasives like the spotted lanternfly. Native to some of the same areas as the joro spider, the spotted lanternfly has proven so damaging to the native ecosystems it’s invaded that people living in these areas have been instructed to kill them on sight.

“Joros are a nuisance to people, for sure, but it’s hard to see actual damage being caused compared to something like the spotted lanternfly,” Davis said.

However, a 2023 article published in Ecology and Evolution offered evidence that the joro might be harming native spider species. Researchers found that the joro was the most abundant spider at half the study sites in which it was present, and that native orb weaver diversity was lower in the places where joros had been present the longest. Though “human population density complicates this finding,” the researchers wrote, their results indicate that the joro “is an invasive species and deserves much more ecological scrutiny.”

More research is needed on this topic, but thus far, the most obvious impact of the joro spider is the intensity of its presence. They’re large spiders that are comfortable living in highly disturbed, urban environments, including porches, decks, gas pumps, and busy intersections, so they’re usually easy to spot.

“Here in Georgia, where we have joro spiders everywhere, you often see them next to native spiderwebs, and they seem to be sort of coexisting, anecdotally, anyway,” Davis said.

What is clear is that joros are not exceptionally aggressive spiders—quite the opposite, in fact. Davis, whose research focuses on animal physiology, wrote a paper in collaboration with one of his students that was published in the scientific journal Arthropoda in May 2023, showing that joro spiders are “extremely shy” compared to other spider species. All spiders exhibit freezing behavior when confronted with a threat, and how long they stay frozen indicates how shy or aggressive they are. Of the ten spider species observed for the study, most remained immobile for less than a minute after being threatened, but the joro spider stayed frozen for more than an hour, making it “one of the shyest species of spider ever documented,” Davis said.

“I’ve had these things crawling up and down my arms, and they seem to be just fine being handled,” he said.

The full extent of the joro’s potential impact on native ecology remains unknown, but scientists are working to color the picture. Davis points out that, while joro spiders may compete for food with native spiders, they themselves are also a food source for other species, including birds. There’s also some hope that joro spiders could serve as a mild check on other invasive species that originate from the same area in Asia to which the joro is native. The joro spider is one of the few creatures known to eat the brown marmorated stinkbug, for instance, and while its North American range does not currently overlap with that of the spotted lanternfly, there have been documented instances of the joro spider eating the lanternfly in their native Asia—though native North American species will eat this insect as well.

“If there’s any good news here, it’s that joro spiders are well suited to eat these critters,” said Davis.

However, joro spiders also seem to have an intuition about species they have not historically been exposed to. In a study published this year in Insects, Davis and his students found that joro spiders, whose native range does not overlap with that of the monarch butterfly, nevertheless avoid eating this insect, whose larval diet of milkweed renders it distasteful to predators. In the study, the spiders attacked monarchs only 20 percent of the time when the butterflies were thrown into their webs, compared to 85 percent of the time for gulf fritillaries and 58 percent of the time for tiger swallowtails, both of which are the same size or larger than monarchs.

“In some cases they’ll even cut the monarchs out of their web,” said Davis. The study states that this outcome “raises many questions” as to how the spiders perceive the monarchs to be distasteful without having eaten them first.

Sometimes other creatures benefit from the joro spider’s catches. In 2022, Davis spoke with National Geographic after hearing from an Atlanta man who saw a female cardinal land on a joro spider web and begin picking food out of it. The observation is a testament to both the strength of the joro spider’s webs and to the unlikely relationships the spiders may form with other species as their population grows.

Ultimately, the joro is likely to spread throughout the United States, and maybe even into Canada. The species is tolerant of human disturbance and often successful at hitching rides on motorized vehicles, and Davis’ research shows that it is more cold-tolerant than other similar species, as evidenced by a 2022 paper published in Physiological Entomology. Another group of researchers published a paper in the September issue of Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity projecting that the spider’s range could one day extend as far north as southern Canada and as far south as the Gulf Coast.

This prediction does not sit well with people who aren’t excited by the prospect of such large arachnids taking up residence outside their homes. But Davis said the spiders aren’t dangerous and may even offer an opportunity to their human neighbors.

“Because joro spiders are so docile, and because they’re so sedentary, and because they live in such close proximity to people,” he said, “you can kind of get to know that spider, and you can use that as an educational opportunity to show your kids what spiders do for a living in the natural world.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.