Some connections in the vast web of life are little easier to see than others. In the Smokies this time of year, black bears lumber up the swaying branches of native cherry trees to feast on dark, sun-ripened fruit. Wood thrushes swoop down from their perches to snatch fat caterpillars and worms from the forest floor. A hungry snail might sample an aging mushroom cap.

But beneath the leaf litter—where trees spread their roots and fungi break down the excesses from the busy world above—these interconnections become harder to decipher. In fact, most of the fauna are invisible to the human eye.

“Soils are very complex systems, and there are a lot of interacting organisms,” explains Dr. Thomas Powers, a biologist and professor at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. “It keeps you humble, but the fact that there’s all this mystery out there . . . to me, that’s exciting.”

Powers has devoted most of his scientific career to studying nematodes—transparent worm-like organisms that range in size from the microscopic to the unsettlingly large, with some parasitic species reaching lengths of more than eight meters. Although their relatively simple anatomy has been described as essentially “a tube within a tube,” Powers says that nematodes play an astoundingly wide range of ecological roles that scientists are only beginning to understand. Some nematodes may cause damage to roots, but others feed on bacteria and unwanted garden insects. Some are even prey for carnivorous fungi, which lure and trap nematodes as a food source.

“For a long time, nematodes were almost synonymous with pests,” says Powers, referring to some garden-variety nematodes that feed on plant roots and damage vegetable crops. “The predominant management tools were nematicides or various pesticides, which were actually quite toxic to humans too.”

More recently, however, nematodes have been receiving attention from both agricultural and environmental sectors as more is understood about their true diversity and functions. Roughly 30,000 distinct nematode species have been described so far, but Powers says scientists estimate there may be tens of millions of species that have yet to be discovered. A full eighty percent of the animals on Earth are nematodes.

The growing interest in nematodes and their subterranean interactions is driven in part by the imperatives of climate change and land development. Studying the dynamic life hidden in soil could be key to more efficiently restoring wild areas, growing food with less energy, and reducing greenhouse-gas emissions that result from farming.

“Now suddenly we’re talking about resilient agricultural systems and soil health, and nematodes aren’t all organisms that you want to eradicate,” says Powers. “There’s some recognition now for those that are providing beneficial services. There’s some intrinsic value to all that diversity.”

Powers has traveled all over the world to study nematodes—from the cornfields and prairies of the Great Plains, to the tropical rainforests of Costa Rica, to the distant glaciers of Antarctica. Thanks to a grant from the National Science Foundation, Powers and a team of fellow researchers have also conducted extensive fieldwork in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The nematodes in the park were of particular interest for a few reasons.

“We were looking at nematodes across various ecoregions, and the Smokies figured into that importantly as a glacier refuge that wasn’t covered during the last ice age,” says Powers. “It was also a very welcoming experimental set-up thanks to the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory (ATBI).”

Launched on Earth Day in 1998, the ATBI is an ambitious partnership between Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the nonprofit Discover Life in America (DLiA) to document every living species in the Smokies. So far, the ATBI has documented more than 20,000 species and is among the largest sustained inventories of natural history in the world.

“In the Smokies, you’ve got so many different habitats,” says Powers. “You’ve got the aquatic nematodes in the streams, and you’ve got the nematodes that are on the balds in the grassy areas, which are very different than the nematodes in old-growth forests.”

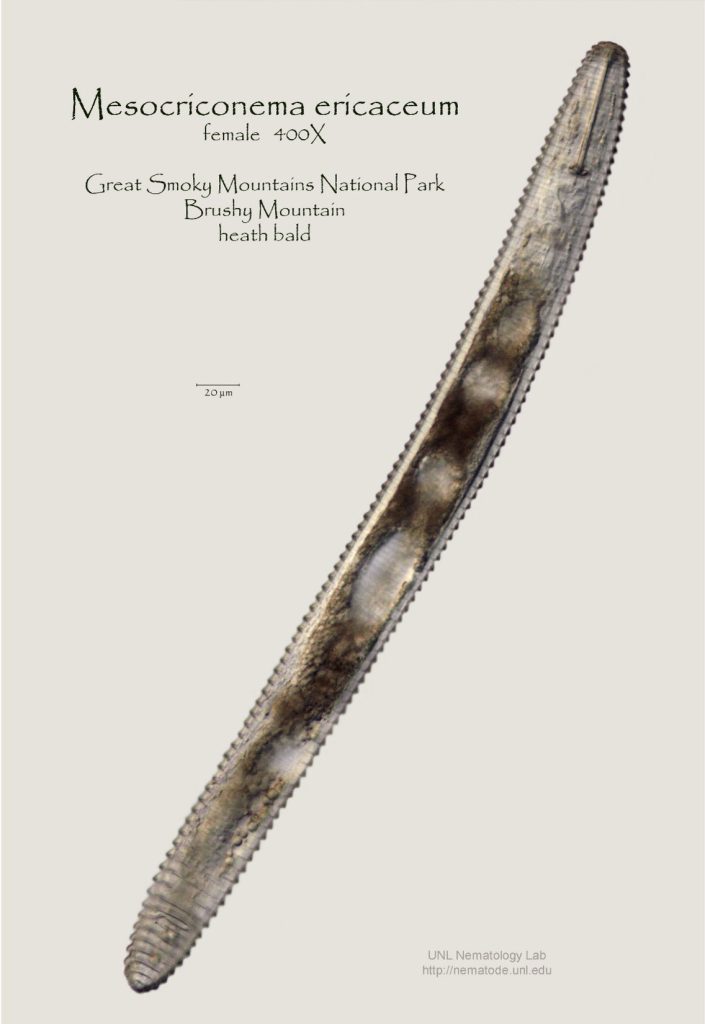

After taking soil samples and carefully conveying them back to a lab, the researchers study the nematodes under a microscope and then analyze their DNA. The most recent species to be described and officially granted a name is Mesocriconema ericaceum, a species the researchers found on a Smokies heath bald near blueberries and rhododendron.

“A lot of these communities were probably formed over tens of thousands of years,” says Powers. “These undisturbed habitats are absolutely unique. You can recreate the plant community but, following disruption like cultivation, you cannot recreate the soil. There’s a kind of romantic notion to that—applying some sort of value to these organisms that you can’t see. It gives you a better sense of place and a sense of time.”

Powers will be sharing more about nematodes and what his team has discovered digging around in the Smokies at the Science at Sugarlands speaker series. The event is hosted by DLiA and will be held at 1 p.m. on Friday, August 19. Registration for the free online event is open at dlia.org/sas.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.