Did you know… about one in every four animals on the planet is a beetle! Of the roughly 400,000 species of beetles known, some are pollinators, others recyclers –some even help to offset the effects of climate change.

“Insects are an instant connection to the wild and an extreme example of Earth’s biodiversity,” says Claire Winfrey, a beetle expert and second-year Ph.D. student in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. “Especially in warmer months, take some time to look in almost any type of habitat and you can find them.”

Claire will speak on behalf of beetles at 1 p.m. Friday, October 19, at the final installment of this year’s Science at Sugarlands series. This family-friendly event is free and open to the public at Sugarlands Visitor Center, 1420 Fighting Creek Gap Road, Gatlinburg. To commemorate its 20th anniversary and provide learning opportunities related to the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory, Discover Life In America has hosted the talks for the past seven months.

FF: How did you become interested in beetles?

CW: Growing up in suburban Oklahoma City, far from “pristine” nature, I was fascinated by all the different types of insects I saw in my neighborhood. For example, I remember the first dung beetle I identified—it was in a small patch of grass between two driveways. Insects got me interested in asking how the Earth supports so many different species and why their habitats differ.

FF: How do we know a beetle from another insects and what are some typical beetles that we might recognize?

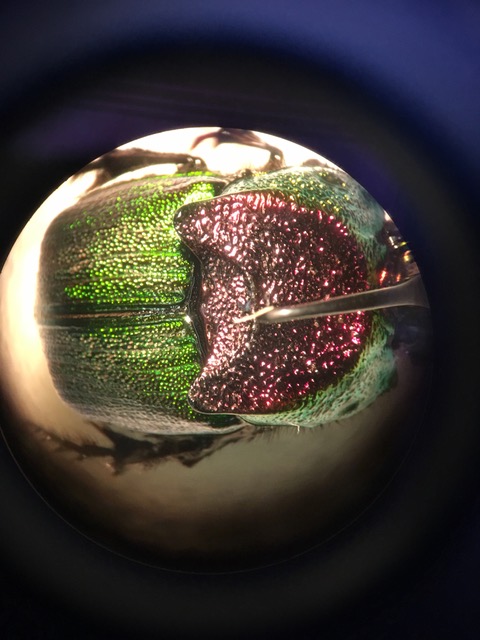

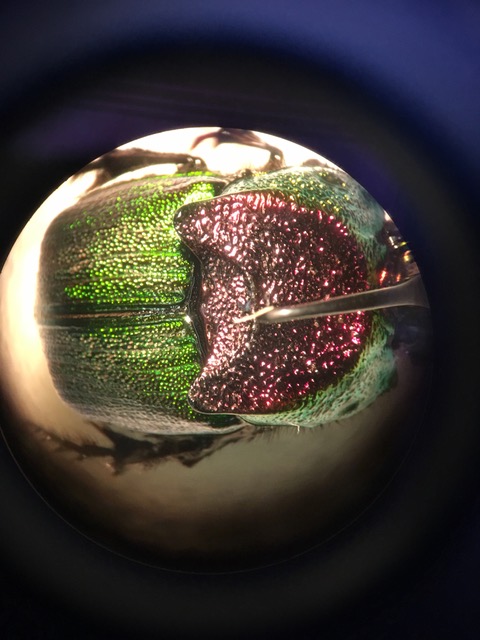

CW: Sometimes it can be a little tricky to tell beetles apart from other insects, especially true bugs, like stink bugs and other bugs that look like them. The sure-fire way to know a beetle when you see it is to examine its back. Beetles have only one set of wings; their forewings are hardened into shell-like structures called elytra. The elytra protects the soft hindwings underneath. This is how you know that insects like weevils, rove beetles, and even fireflies are truly beetles.

FF: Have some new beetles been discovered in the Smokies through the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory and the work of DLIA?

CW: Yes! So far, the ATBI initiative has added 1,952 beetle species to those known in the park; 61 of these species are new to science.

FF: Why are beetles important for the sustainability of our planet?

CW: With so many species, beetles have a huge impact on ecosystem function. Many people know that beetles comprise a large proportion of crop pests, so understanding their ecology and how to keep their numbers under control is important for the world’s food supply. Yet beetles also help some of our favorite plants. For example, ladybugs eat aphids that threaten crops, and, surprisingly, most flowering plants are actually pollinated by beetles.

One of my favorite facts about beetles, specifically the dung beetles that I study, is that they are the animal world’s great recyclers. Dung beetles can clear about 80 percent of the dung from cow pastures. They then bury this dung alongside their eggs as a food source for their young. However, most of this buried dung is not eaten by the beetles, but returns to the soil to fertilize plants.

FF: What are the main challenges facing beetles and those who study them?

CW: Beetles are incredibly biodiverse, so much, in fact, that it can be hard even for beetle experts to correctly identify some of the species. Beetle taxonomists are constantly re-evaluating evolutionary relationships between beetle species and updating guides for identification. There are still many, many beetles that require a microscope to identify them down to the correct species.

On an even more serious note, beetles and overall insect numbers are in decline worldwide. A study in Germany found that flying insects have decreased by about 75 percent in the past 27 years. The study’s authors identified pesticides as a likely culprit. Pesticides do not stay where you spray them; instead, they travel through the air and water to harm non-targeted insects. Pesticides – along with land-use change and global warming – threaten beetle species worldwide.

FF: What are some of the ways readers and guests of the park can help beetles thrive?

CW: In general, doing your best to not disturb their habitat in the park is important. Sticking to the trails helps keep leaf litter – where many beetles live – in good condition. In your own yard, consider limiting leaf raking in the fall. Leaf litter provides a warmer place for beetles and other insects, like butterflies, to overwinter. Plus, limited raking means your soil will be healthier in the spring. Finally, cease insecticide use. Insecticides are not specific; they kill harmless ladybugs and butterflies as easily as they kill the bugs munching on your lettuce. If pests are a problem in your garden, consider applying less harmful alternatives like dormant oil or fatty acid salts.

FF: What else can folks look forward to during your discussion on October 19?

CW: Beetles get a bad rap in the context of the Smoky Mountains. Invasive species that target trees, like the emerald ash borer, cannot be taken lightly. However, beetles are an important part of a healthy forest ecosystem. During my discussion, we will talk about all the surprising ways beetles help keep the Great Smoky Mountains ecosystem functioning – from pollination, to keeping out invader species, to even reducing global warming gases.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.