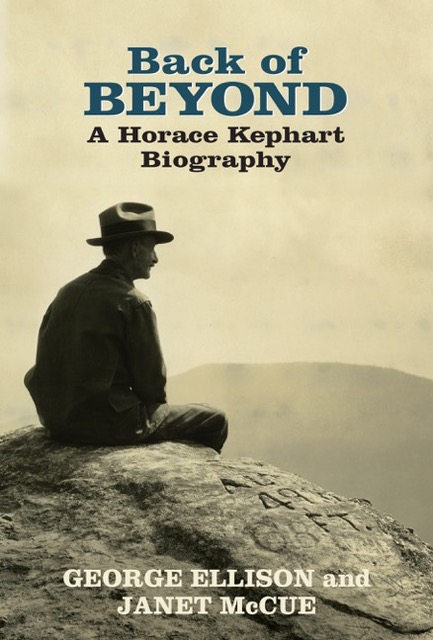

Working with literary authorities George Ellison and Janet McCue to edit their new book, Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography, was like being a roadie for a dynamic singer-songwriter duo (imagine going on tour with Van Morrison and Joni Mitchell). George and Janet are so creative, so steeped in the literature of the Smokies region, and so attuned to all things Kephart that it was mesmerizing and magical to interact with them on a daily basis.

As we anticipate the book being available in stores and on our website later this month, I interviewed the authors to learn more about how they came to write this 500-page GSMA title, which includes more than 80 historic images from park archives, the Horace Kephart Family Collection and other sources.

Frances: What does Back of Beyond offer to readers that they cannot get from any other source?

George: As it should, the biography provides for the first time an understanding of Horace Kephart’s entire life—not just random bits and pieces such as those often heard in conversation, many of which are anecdotal or outright fabrications.

Frances: What would you tell a GSMA member considering buying the book?

Janet: Kephart is a man full of contradictions—solitary yet a masterful storyteller; generous yet indebted; conventional yet unconventional; a loyal friend and an absent parent. Back of Beyond explores this complexity, revealing a talented man who from the abyss of his breakdown in 1904 found the fortitude to build a worthwhile life in the Smokies.

Frances: George, how did you first come to be interested in Kephart?

George: I have always enjoyed outdoor, travel and adventure books. In grad school at the University of South Carolina during the late 1960s, I focused on the tradition of descriptive-humorous-sporting literature that flourished in the Southern states in the 19th and early 20th century. Mark Twain took the basic ingredients found in these materials and in 1883 wrote an American classic, Life on the Mississippi.

When I discovered Kephart’s two major publications, Camping and Woodcraft and Our Southern Highlanders, carried that genre into the next century, I became increasingly curious about Kephart and started looking into his life and work. The University of Tennessee Press wanted to reissue Our Southern Highlanders and asked if I’d consider writing an introduction. Now, half a century later, here I stand, up to my chin in Kephartiana—all because I said, “Yes.”

Frances: How did Janet enter the picture?

George: I first met Janet at Kephart Days in Bryson City, about 2009. Several years prior to that she had sent me a draft essay based on her interest in librarianship in general and Kephart in particular because of his long-standing association with Cornell University and Ithaca, New York. But alas I read only the first half of the essay because it seemed to be just another version of the material with which I was already quite familiar.

After the event I was going through my stacks of boxes and happened upon the essay yet again—and this time read it all. Therein I discovered the first accounts of Kephart’s life in St. Louis, especially the events surrounding his breakdown and attempted suicide. I was flabbergasted by the amount of material Janet had accumulated from various sources as well as the orderly manner in which they were organized. So I called Steve Kemp, the editor (now retired) at Great Smoky Mountains Association, and told him I had found the perfect person to co-author the Kephart biography. He agreed and I was right.

Frances: Janet, how did your Kephart journey begin and lead you to your co-author?

Janet: George and I have been chasing Kephart for 50 years, following parallel paths and finally intersecting in 2009 at Kephart Days. A footnote, a millstone, an Alaskan librarian, and a heavy dose of serendipity all played a part.

My husband’s well-worn copy of Camping and Woodcraft inspired us to find the millstone marking Kephart’s Bryson Place campsite during a 1970s backpacking trip in the Smokies. An assignment for a research methods course in grad school led me to delve into Kephart’s early writings on librarianship.

After graduating from the University of Michigan in 1979, I was offered a position as an academic librarian at Cornell University where Kephart had been a graduate student one hundred years earlier, in the 1880s. While reading a book about women in librarianship, I noticed a footnote citing a letter from Kephart to a fellow grad student at Cornell, Harry Lyman Koopman, which led me to a trove of letters at Brown University. Kephart’s correspondence with Koopman revealed much about his courtship of Laura, and later the Kephart’s’ attempted reconciliation in 1908.

It was a colleague on the west coast who alerted me to a play about Horace Kephart that an Alaskan librarian, Dennis Stephens, had written and produced. When I contacted Dennis, he invited me to attend Kephart Days in Bryson City where I met George.

Frances: Where did you do most of your research for Back of Beyond?

Janet: Hunter Library at Western Carolina University has the most extensive collection of Kephart material. Equally important, though, are significant research collections at Brown University, Cornell University, University of Tennessee, McClung Library, Pack Memorial Library, and the St. Louis Mercantile Library. It was serendipity that led me to Brown, so we suspect that there are collections as yet undiscovered, which will lead researchers to further insights.

Frances: What was the most surprising thing you uncovered during your research?

George: Over the long haul, it’s the depth of connection between Horace Kephart and his father. Isaiah Lafayette Kephart was, as they say in the mountains, “much of a man.” Despite areas of disagreement, Isaiah stuck by Horace through thick and thin. He instilled the desire that fueled Horace’s now-famous venture into the southern hinterlands; in the biography, I describe him as a coconspirator in the quixotic search for a back of beyond.

Almost exactly one year after Horace had pitched camp outside Dillsboro, Isaiah showed up on Hazel Creek to make a first-hand inspection tour via foot or mule of what sort of land his son had discovered. Because of Isaiah’s forbearance, they were able to maintain a meaningful relationship that was one of the most significant in Horace Kephart’s life.

Frances: Was there some information you wanted for the book that was nearly impossible to find?

Janet: We are still looking for clues about J.B. “Andy” Anderson, a good friend of Kephart’s. We have photos of him; Kephart writes that he lived with him at the Hall Cabin; and we know from a memoir that Andy played the ukulele, wore a flower in his lapel, and probably hailed from Massachusetts. Although we’ve chased down lots of possibilities, we’ve not been able to positively identify him since there are many Andy Andersons in the world and just as many Andersons with the initials J.B. We’re hoping that with the publication of Back of Beyond, we’ll hear from a descendant of Mr. Anderson.

George: Also difficult to fill in was the mostly blank period when Kephart left Hazel Creek in 1907 and didn’t return to Bryson City until 1910. As of today, I think we have filled in that period pretty well. The surprise for me is that Kephart lived in East Tennessee for a good while.

Frances: It seems that filling in the gaps in Kephart’s life was almost like a puzzle, requiring years of research. What inspired you to persevere in such a monumental task?

Janet: Indeed Kephart was a private man, explaining in his autobiographical sketch, “Horace Kephart by Himself” that “much else has been left out.” This admission in effect became an invitation to discover the hidden stories.

In writing Back of Beyond, George and I sought to humanize the man, eliminate some of the mythology, evoke recurring themes, and tell the backstories. Given Kephart’s natural reticence, much of his story is revealed by others. It’s an ensemble cast of friends and family—Koopman, Laura, Bob Barnett, Margaret Gooch, Paul Fink, George Masa, I.K. Stearns—who help flesh out the character and personality of Horace Kephart.

Frances: We have been hearing from a lot of GSMA members wondering when the book will be out. What do you think is its special appeal, and how will it be received?

George: I once had a 45-minute slide-lecture program about Horace Kephart titled “A Place of Refuge” that I put together for the park’s 50th anniversary and continued to present up until a few years ago. Without exaggeration I must have presented the thing over 75 times for Elderhostels, Rotary, Jaycees, Outward Bound, libraries, private homes, park visitor centers, book stores, etc. I learned a lot of things in doing so, but mainly that Kephart has this incredible built-in following no matter where you go—more so, of course, in the southern mountains and adjacent areas, but also on a national level. You don’t have to sell Horace Kephart—just let it be known where and when something will take place and unlock the doors.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.