It’s possible to hike hundreds of miles in Great Smoky Mountains National Park and never see a salamander. Even so, an exceptional number of the amphibians make their home in the mountains.

Scientists have identified 31 species of salamander in the Smokies and might be on the precipice of adding another. They range from tiny specimens a few inches long to the well-named, sometimes-fierce hellbender, which often reaches a foot in length.

With thousands of these creatures roaming virtually every corner of the park, a question arises: Why are they seldom seen? Are they really that slippery?

No, says Jonathan Cox, who studies salamanders and their habitats as part of his work as a park biological science technician. He often can be found boot-deep in park wetlands.

“Salamanders are very elusive and cryptic,” Cox said. “Their habitat ranges across a lot of different ecosystems from terrestrial to fully aquatic, but throughout all those ecosystems they’re usually nocturnal. They come out at night to forage for food and to mate. During the day, they’re typically under logs or under rocks in streams or under large boulders.”

Daytime is not the right time if you’re a salamander.

“They’re looking for more optimal microclimates,” Cox said. “Usually the temperatures are too high during the day, and there’s also the risk of predation. They spend the day resting inside those refuges to find better climate and to hide from predators.”

Salamander predators include ring-necked and garter snakes, large birds, and yes, other salamanders. Some larger salamanders share habitats with smaller members of the species and sometimes have them for lunch.

The Smokies’ wildly diverse habitats are responsible for the wide range of salamanders in these mountains. “You’ll find some on the west side of the park but not the same ones on the east side,” Cox said, “and there are types of salamanders on the North Carolina side that you don’t find in Tennessee. Certain species live in the center of stream channels but not on the edges.”

So how can the casual park visitor without a science degree encounter a salamander? Hit the trails in the evening with a flashlight, Cox said.

“The red-cheeked salamander is endemic to the Smokies and one you’re most likely to see,” he said. “Walk into the spruce-fir forest, maybe around Clingmans Dome or Newfound Gap as it’s getting dark, and you’re likely to see some. You’re likely to see blackbelly salamanders in the Greenbrier area of the park. Right after sunset they get going with foraging and mating. They’re less active as morning approaches.

“Two of the peaks of activity are after the thaw in higher elevations and once the temperature begins rising. Early summer and early fall are good times. There’s a decline of activity in the heat of the summer, and they’ll sometimes go underground during the night because of lack of moisture.”

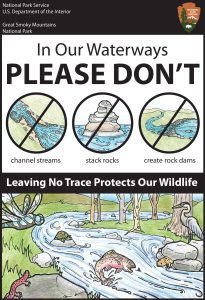

Visitors should avoid lifting rocks in or near streams in search of salamanders—or anything else. “Their climate is under cover—a log or a rock,” Cox said. “By flipping it, we totally disrupt that. Many salamander species in the park are lungless. They respire—or breathe—entirely through their skin. When we handle them, the oil in our hands gets transferred to their skin, and it makes it more difficult for them to breathe.”

Much remains unknown about the park’s salamander population, including the breadth of its diversity. Researchers recently identified a possible 32nd species, one that was found along Cosby Creek just downstream from the park. Indications are that the newest salamander might be found inside the park in several locations.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.