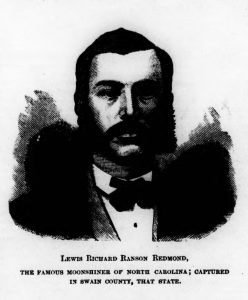

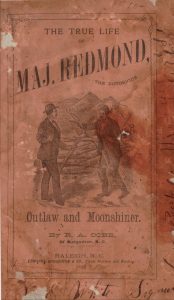

No one was more responsible for the romantic image of the moonshiner than Lewis Redmond. His story was chronicled in newspapers including the New York Times and the Atlanta Constitution, the National Police Gazette (a periodical geared toward the curious public), a short book entitled The True Life of Maj. Redmond, the Notorious Outlaw and Moonshiner (supposedly nonfiction), and two dime novels, one of which bestowed him with the title “King of the Moonshiners.” The escapades of Redmond and his fellow moonshiners, often depicted as a kind of Robin Hood and his band of merry men, inspired color writers like Mary Noailles Murfree to portray the moonshiners as a unique artifact of the Smoky Mountain region.

No one was more responsible for the romantic image of the moonshiner than Lewis Redmond. His story was chronicled in newspapers including the New York Times and the Atlanta Constitution, the National Police Gazette (a periodical geared toward the curious public), a short book entitled The True Life of Maj. Redmond, the Notorious Outlaw and Moonshiner (supposedly nonfiction), and two dime novels, one of which bestowed him with the title “King of the Moonshiners.” The escapades of Redmond and his fellow moonshiners, often depicted as a kind of Robin Hood and his band of merry men, inspired color writers like Mary Noailles Murfree to portray the moonshiners as a unique artifact of the Smoky Mountain region.

According to Dan Pierce in Corn from a Jar, Redmond, who was born in 1854, began his illegal whiskey business in what is now Transylvania County, North Carolina. In 1876, he shot and killed federal marshal Alfred Duckworth when the marshal stopped Redmond in the process of transporting his contraband product. He then fled to South Carolina where he established an extensive moonshine operation employing a gang charged with defending the moonshine enterprise and terrorizing federal officers.

George Atkinson, in After the Moonshiners, describes the then 37-year-old Redmond as being uneducated but with a “great deal of native cunning and shrewdness.” Atkinson relates a story that purportedly Redmond told about himself. Redmond was on his way to Asheville with five barrels of “the precious fluid” hidden in a wagon under a pile of corn husks. He was wearing a disguise of a beard and butternut clothes* in which “my dearest friend would not recognize me.”

Three men who Redmond recognized as deputy marshals because of their pistols and Winchester repeating rifles approached him. Redmond proceeded to chat with the officers, pretending ignorance about their intent. When they asked where they might get some whiskey, Redmond faked a “cracker” accent and told them that no one dared to make whiskey anymore because they were afraid of the marshals. When pressed, he confessed that he did have a few gallons under his seat that he used “for his stomach’s sake.” He then offered to fill up their flasks. They took him up on the offer. After enjoying a drink together, Redmond and the marshals parted ways. Redmond proceeded on to Asheville. He subsequently made many more similar trips, utilizing both guile and disguise.

As the pressure of federal agents intensified, Redmond decided to move to the Smokies region of North Carolina in 1879, settling in what is now Bryson City. According to Pierce, he continued his moonshining activities but at a more modest scale. Redmond reportedly told the Smoky locals that “there are not enough men in Swain County to arrest me.” Apparently, the Swain County residents agreed because they chose to ignore his illegal activities. Seven federal agents tried to arrest him but failed. Redmond outsmarted them by escaping through the chimney of his home.

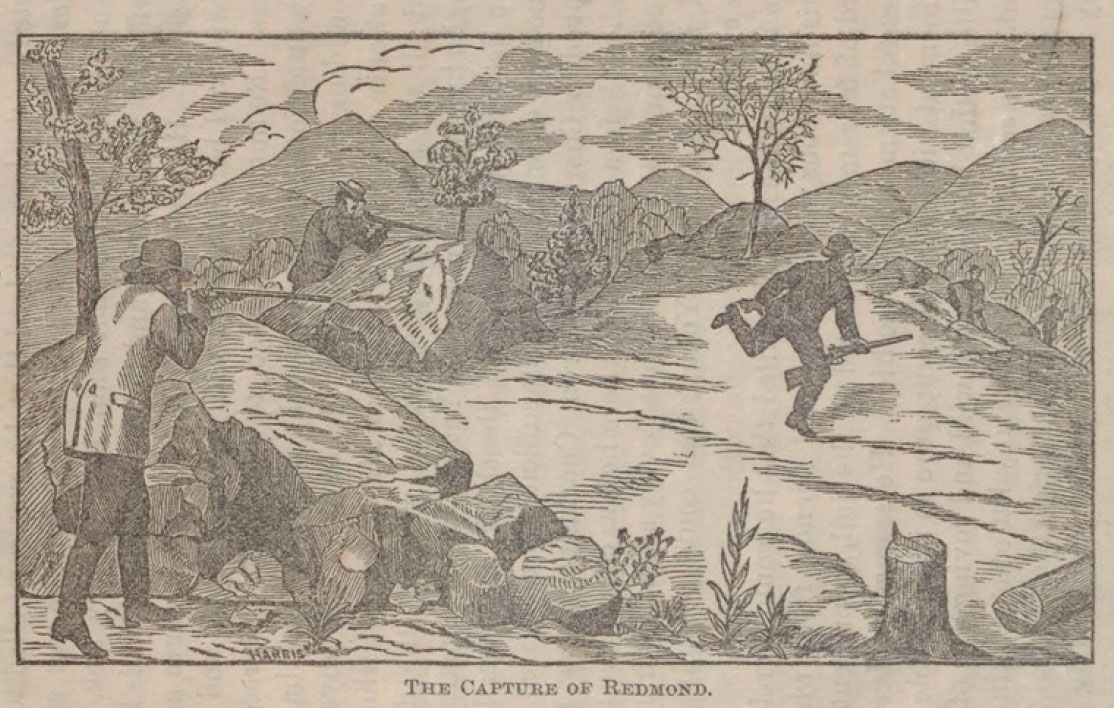

The marshals finally caught up with Redmond in 1881. The events surrounding his capture were related in the National Police Gazette. Redmond told the story as follows:

Despite being shot several times, Redmond survived to face trial in federal court. According to Pierce, the prosecutors decided not to charge him with the murder of Duckworth. In exchange, Redmond pled guilty to violations of federal revenue law and criminal conspiracy. He was sentenced to ten years in federal penitentiary in Auburn, New York. After serving three years, he was pardoned by President Chester A. Arthur.

After his pardon, Redmond returned to South Carolina, finding work with the Biemann distillery, a legal operation, in Oconee County. The distillery capitalized on Redmond’s fame calling a new brand of whiskey “Redmond’s Moonshine” and gracing the bottles with a picture of the famed moonshiner. The New York Times reported his return and his new legal profession. But one article called him a “physical wreck and an invalid.” He had apparently contracted tuberculosis in prison.

Redmond lived out the last years of his life as a quiet farmer, husband, and father to several children. When he died in 1906 at the age of 54, his family had inscribed on his tombstone “He was the sunshine of our life”—a curious epitaph for a man who lived such a notorious life.

* “Butternut clothes” refers to garments dyed with walnut and butternut leaves and shells, which were commonly worn by Confederate soldiers and an indicator of poverty.

Sources

Atkinson, George Wesley. After the Moonshiners. By One of the Raiders. A Book of Thrilling, Yet Truthful Narratives. Wheeling, WV: Frew and Campbell, 1881. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433007090339.

Pierce, Daniel S. Corn from a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains. Gatlinburg, TN: Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2013.

“Redmond, the Outlaw Moonshiner.” The National Police Gazette 38, no. 191 (Saturday, May 21, 1881): 4. https://ia802302.us.archive.org/17/items/sim_national-police-gazette_1881-05-21_38_191/sim_national-police-gazette_1881-05-21_38_191.pdf.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.