Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series revisiting a notorious murder in the community known as Chestnut Flats in Cades Cove and the dangerous but lucrative enterprise of distilling illegal spirits in the Great Smoky Mountains prior to the creation of the national park. Read the first part here.

In June of 1899, a grand jury ultimately failed to indict the Cades Cove moonshiner “Uncle Sam” Burchfield for the murder of George Powell Jr. As reported in the Maryville Times, Burchfield’s arrest and subsequent trial had been sparked by new evidence of his involvement in the murder that had occurred at the Powell home in Chestnut Flats two years prior. A letter written by Burchfield’s son-in-law Hale Hughes, who was serving time in federal prison for the murder, claimed that it was in fact Burchfield who had pulled the trigger that fateful December afternoon, and prosecutors had reportedly gathered 16 witnesses, at least initially, who could testify to Burchfield’s various illegal activities related to distilling whisky. Nevertheless, Burchfield was exonerated, and not only that—he lived to enjoy a certain amount of regional celebrity.

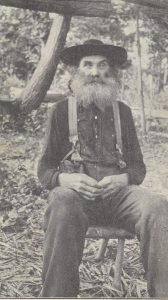

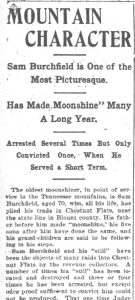

The Knoxville Journal and Tribune published a long article about Burchfield with the headline “Mountain Character. Sam Burchfield is One of the Most Picturesque. Has Made Moonshine’ Many a Long Year. Arrested Several Times But Only Convicted Once, When He Served a Short Term.” The article is part of a clipping from the April 22, 1900, edition of the newspaper shared on the Find a Grave entry for Burchfield, presumably posted by a descendant.

According to the article, Burchfield was the oldest moonshiner at age 70. If the date on the article is correct, he was actually 60 years old—not 70. He had been raided many times by revenue agents but only convicted once and given a six-month sentence in the county jail. Two men informed the revenue agents on the location of Burchfield’s still, but “they did not live long to enjoy their reward. They were quietly put out of the way. But no one attached Burchfield to their taking off.” The article is ambiguous. Did they leave town, or were they killed? The writer of the article went on to say, “The imprisonment was a terrible ordeal for the free spirit of Sam Burchfield, but to him it was not a punishment for moonshining but for being caught at it.”

The Knoxville Journal and Tribune article praised Burchfield as a fair man to his neighbors. He would not give out information about his moonshining associates and customers when on trial. He allowed his neighbors to use his grist mill free of charge, and his moonshine was judged to be the “best in the mountains,” which undoubtedly enhanced his reputation.

Interestingly, Burchfield was given permission by federal authorities to operate a moonshine still at the 1910 Appalachian Exposition held in Knoxville. On September 12, 1910, the Knoxville Sentinel ran a feature article, seemingly based on an interview with Burchfield himself, outlining his contribution to the exposition. The article provided a somewhat sanitized version of Burchfield’s life story. The writer was clearly impressed with Burchfield’s tall stature and his extreme hairiness. Burchfield also had a rifle with him that he inherited from his father. With this rifle, he said he had shot about 75 bears but not once used it to shoot a man. He moved to the Smokies when he was a child and never left, raising his family of ten children there. Although his wife had died three years prior, in 1907, all of his children at the time of the article were living nearby.

An advertisement for the still exhibit appeared in the Knoxville Sentinel calling him “Uncle Sam Burchfield, the veteran moonshiner of the Appalachians.” Admission was ten cents, and a souvenir was given to every visitor. No information was given about what the souvenir was.

In a final note to this story, Martha Gregg Powell, widow of George Powell Jr., stayed in Cades Cove. In the 1900 census, she is listed as a farm laborer and a head of household with four children. In 1908, she married John Noah Burchfield. Obviously, she didn’t blame all the Burchfields for her first husband’s murder. Unfortunately, she died three years later at the age of 39.

Burchfield died in 1917 and is buried in the Cades Cove Primitive Baptist Church Cemetery.

As for Hale Hughes, the Knoxville Sentinel reported in December 1908 that he had been pardoned. The article was quite short but does say that “some people doubt his guilt.” In the 1920 federal census, Hughes was reported as living in Tellico Plains with his wife Mary Ann, two children, and two grandchildren. He was working as a carpenter and owned his own home. He died in 1927 at the age of 61. With the death of Mary Ann in 1931, all the key players in this story were gone, and any details yet given died with them.

Digital sources

Find A Grave (findagrave.com) is an excellent source of information, especially for individuals buried in the Cades Cove cemeteries.

Some issues of the Maryville Times can be found in Chronicling America, (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov), a free newspaper resource from the Library of Congress.

Book sources

Dunn, Durwood. Cades Cove: Life and Death of a Southern Appalachian Community. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

Pierce, Daniel S. Corn from a Jar: Moonshining in the Great Smoky Mountains. Gatlinburg, TN: Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2013.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.