The four-state mountain region that includes Great Smoky Mountains National Park is home to an estimated 14,500 black bears, but one particular animal had caught the attention of a watchful police chief in one of the park’s gateway communities. The bear hadn’t hurt or threatened anybody—yet—but it kept getting into things it shouldn’t, and efforts to encourage residents to secure attractants like garbage, bird seed, and pet food kept falling flat.

“The police chief reached out to me and said, ‘This bear is a really beautiful bear,’” recalled Janelle Musser, black bear support biologist for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. “‘It’s not really doing anything that bad, but I just fear if you don’t relocate it now, you’ll have to put it down.’”

Wildlife managers in bear country often get these kinds of calls. A neighborhood bear starts developing bothersome or even dangerous habits, and people ask agencies like TWRA to take what they see as the most logical next step: move the bear somewhere else.

But “relocation may not be the happily ever after that most people think it to be,” said Kristin Botzet, whose recently completed master’s thesis offers the most detailed look yet at what happens to black bears moved out of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Their chance of surviving the first year after relocation, she found, is just 10 percent.

Botzet worked as a wildlife research technician for five years before starting her graduate program at the University of Tennessee Knoxville in 2021. While relocating grizzlies and black bears in northern Idaho, she started wondering whether anyone had ever used GPS collars to get an in-depth look at what happens once a bear is moved. Discovering that no such study existed, she reached out to multiple graduate programs in her quest to pursue that question. Botzet eventually connected with research ecologist Joe Clark, who would become her advisor at UT. Clark was already working to secure funding for just the type of project Botzet had in mind.

Between 2021 and 2023, Botzet worked with officials from Great Smoky Mountains National Park and TWRA to capture 27 bears exhibiting conflict behaviors in the park and relocate them to release sites in Cherokee National Forest. She also obtained National Park Service data from an additional 23 bears relocated between 2015 and 2020. All 50 bears had been exhibiting behavior that showed a potentially dangerous level of comfort with humans and their food.

From most of these bears, Botzet was able to obtain hair samples, which she analyzed for molecular information indicating whether their diet was composed primarily of natural foods or human foods. In the months following these captures, GPS collars fitted on each bear transmitted precise location data.

Botzet compared this information against similar data from an additional 37 bears that had not been engaged in conflict, which she captured and released in the Pigeon River Gorge, near release sites for relocated conflict bears. Her study also considered data from 39 conflict bears that had been captured and re-released inside the park between 2016 and 2018.

“Previous research has alluded to, when you relocate bears, they move a lot,” Botzet said. “We knew that going into it, but the degree of it was kind of surprising.”

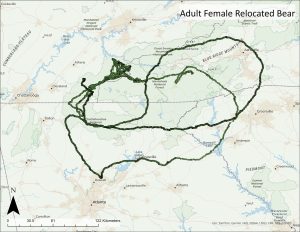

In the six months following her relocation, one adult female in Botzet’s study, bear 1173, covered 1,000 miles touching four states. At one point the bear came within five miles of her original capture location but continued on to den about 11 miles from her release site. This bear was healthy and had reared cubs in previous seasons, but she did not give birth that winter. Another bear, also a female, traveled nearly 750 miles through four states during her nine-month monitoring period, though she never came close to her capture location.

All this travel, combined with the stress of relocation, leads to perhaps the most poignant outcome of Botzet’s study: relocated bears were 96 percent less likely to survive the next year than conflict bears that remained inside the park. Compared to the 10 percent probability of survival for relocated bears, Botzet found an 87 percent probability for conflict bears that stayed in the park and an 84 percent probability for resident bears without reported behavior issues.

For relocated bears, hunting was by far the most common cause of death, with a risk more than 11 times greater than for resident bears.

“Hunting is prohibited in the park boundary, so these bears went from a protected area to an area where bear hunting is very popular and there’s a lot of hunting pressure,” Botzet said. “Likely, the combination of them being unfamiliar with their surroundings with that new pressure put them at higher risk of being harvested than their resident counterparts.”

TWRA views hunting as a tool for managing population growth, not for managing conflict with humans. Relocated bears make up a very small proportion of the overall harvest.

“Taking these bears in harvest is not changing conflicts in the landscape,” Musser said.

Within one year, nearly one-third of the surviving adult bears in the study returned to their original capture location, with young male bears more likely to remain near the release site. In many cases, conflict behavior persisted, an outcome that was more likely in bears whose hair analysis indicated a heavier reliance on human food prior to relocation. The probability of a relocated bear’s behavior being reported to a wildlife agency within the next year was 45 percent, and the probability of conflict rose to 63 percent when factoring in GPS data. Bears hanging around homes and other human developments indicated the possibility of additional, unreported conflicts.

“Food conditioning is really hard to reverse once it’s taken root,” Botzet said. “Once you have a food-conditioned bear, you pretty much have to remove the potential rewards completely, and it’s just not possible to do that.”

It’s even less possible now to totally remove a bear’s access to food rewards than it may have been a couple decades ago. Between 2010 and 2020, populations in North Carolina and Tennessee grew by 903,905 and 564,736 respectively, according to US Census Bureau data. Dan Gibbs, black bear program coordinator for TWRA, said that the bear population in East Tennessee increased by about 1,000 during that same period.

“Fifteen, twenty years ago, we had more areas that we could take the bears where they weren’t as likely to have interaction with people, and they weren’t as likely to run into other bears that were protecting their home range,” he said. “And so the success of moving them has definitely gone down over the last few years.”

From an outside perspective, relocating a bear may seem like an easy fix, allowing the bear to embark on a new life and relieving residents of potential danger: a win-win solution. But the new research indicates otherwise, as Musser told the police chief who called her about the neighborhood bear.

“I said, ‘Unfortunately, if I move it, it’s an even higher chance that it will not survive,’” she said. “And I explained Kristin’s research.”

The police chief was crestfallen, but the knowledge motivated him to address the heart of the issue. He realized, Musser said, that TWRA’s reluctance to move the bear stemmed from concern for its welfare, and that saving it would require its human neighbors to step up. Even if TWRA relocated the bear in question, it wouldn’t have been long before another bear discovered the food source that had attracted the first animal.

Gateway communities are taking steps to reduce food conditioning. In recent years, programs in Asheville and Gatlinburg have distributed bear-resistant dumpsters and trash carts to homes and businesses, and in October 2024 the government of Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, voted to transition its city to bear-resistant dumpsters. BearWise®, a cooperative effort including 44 states, continues its work to educate people about how to safely live and recreate in bear country. However, litter, unsecured garbage, and gaps in knowledge pose continual challenges.

“In terms of what’s next, I think it’s more the questions of what can we do as bear biologists, bear managers, to focus more on the human component of human–bear conflicts,” Botzet said. “What can we do to better shift it towards addressing the root of the problem?”

To help protect black bears where you live or travel, follow the BearWise Basics at BearWise.org.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.