In 1927, a $5 million donation from the richest man in America—the equivalent of $92 million today—secured the Great Smoky Mountains’ then-tenuous future for protection as a national park. But when John D. Rockefeller Jr. agreed to write the check, he had never so much as glimpsed these ancient peaks. Smokies Life’s former publication director Steve Kemp spent years wondering: why?

“Most people just said, well, he had more money than he knew what to do with,” Kemp said in a recent interview. “Having known some wealthy people, very few have that problem. And the Rockefellers especially were very thrifty and very careful with their money.”

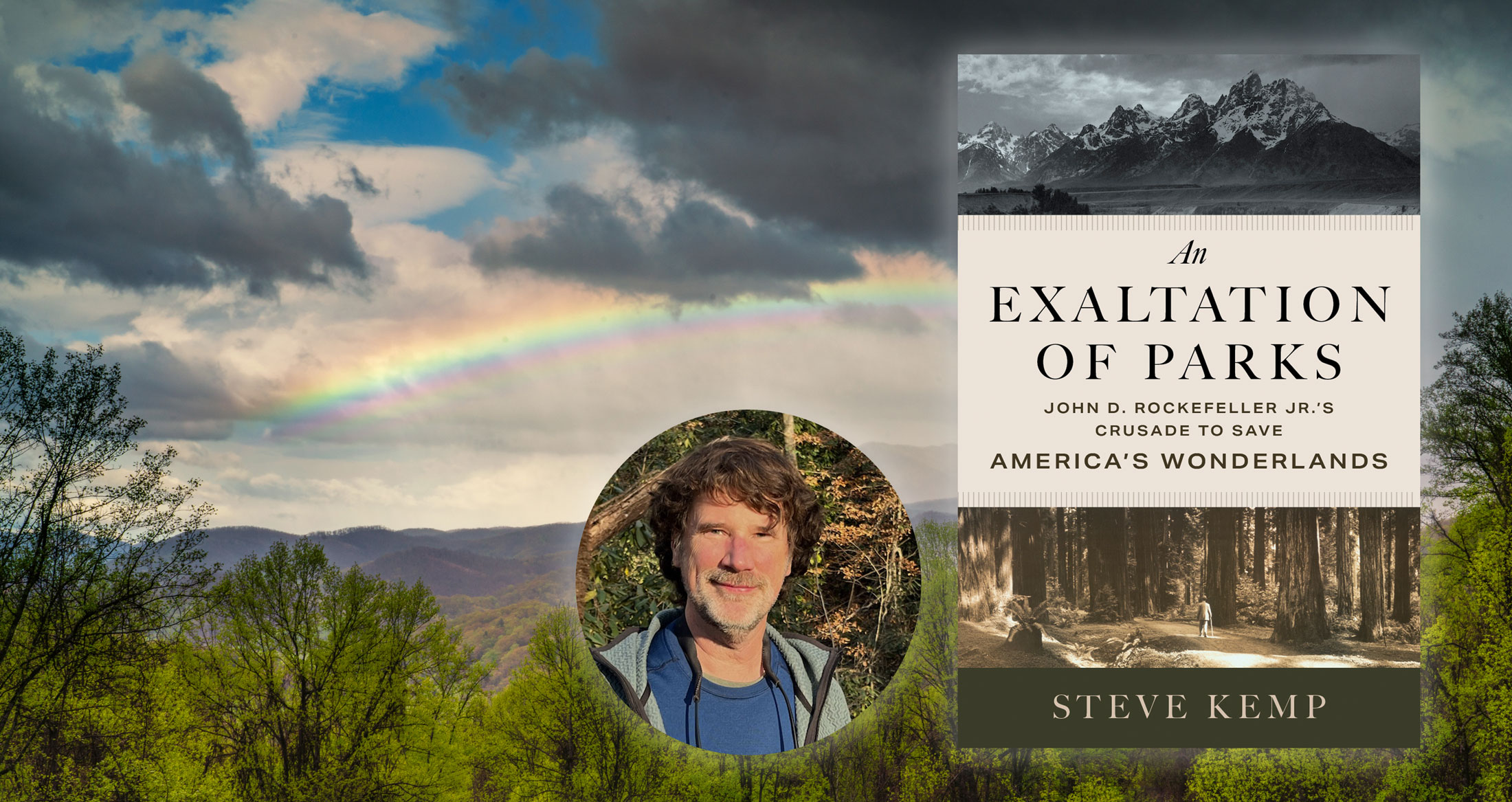

During his 30-year tenure with Smokies Life, Kemp often considered writing a story on the topic, but he knew the research phase would require him to spend multiple days at the Rockefeller Archive Center in upstate New York. Amid his myriad other job responsibilities, he could never spare the time. After retiring in 2017, it was one of the first stories he set out to do—the resulting piece, “Angels Can’t Do More,” appeared in the fall 2019 issue of Smokies Life Journal.

Kemp quickly realized that Rockefeller Jr.’s importance to the national parks effort was much bigger than the Smokies.

“You couldn’t explain why he was so generous with the Smokies until you traced the whole trajectory of his life and his philanthropy,” Kemp said. “So I did the article but immediately started thinking about the book too.”

That book—An Exaltation of Parks: John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Crusade to Save America’s Wonderlands by Steve Kemp, published by the University of Utah Press—came out in July. Covering a timeframe from 1908 to 1950, it looks well beyond the Smokies to explore the roots of Rockefeller Jr.’s involvement with land preservation in what would become Acadia National Park. It then travels to beloved sites across the country: Mesa Verde, Yellowstone, Grand Tetons, Shenandoah, Yosemite, the redwood forests of California, the Blue Ridge Parkway, and, of course, the Great Smokies.

“For him, the Smokies were probably his easiest project, because the grassroots conservationists and business boosters did all the work,” Kemp said. “They just recruited him at the end to come in and write the big check. But most of his other projects he was involved with from the very beginning.”

During Rockefeller Jr.’s lifetime, the Rockefeller family was one of the wealthiest—if not the wealthiest—families in America due to Rockefeller Sr.’s success in the oil business. But their lifestyle and overall approach to wealth was much different from the rest of the Gilded Age tycoons who, as portrayed in contemporary works like The Great Gatsby, loved lavish parties, luxury yachts, and ostentatious displays of excess. To the contrary, Kemp writes that Rockefeller Jr.’s college friends at Brown University “once chided him for ‘trimming frayed edges on his cuffs or standing in rapt concentration over a teakettle’ attempting to separate two conjoined postage stamps.”

“It’s worth noting, however, that Rockefeller thrift was never practiced with the aim of purchasing larger yachts or more brilliant jewels, since neither Junior nor his parents considered such luxuries alluring,” he continued. “Money and its conservation were important to the Rockefellers because they believed their money had a purpose.”

Steadfast northern Baptists, the Rockefellers were “largely motivated by their Christian morals and sense of duty” in their philanthropy, Kemp wrote. “Senior viewed himself as a ‘steward of wealth which God had placed in his trust.’”

Even before amassing his fortune, as a struggling teenager shouldering the formidable task of supporting his mother and younger siblings, Rockefeller Sr. took generosity seriously. In addition to “punctual” tithing to his own church, he made small contributions to an African American church and Catholic orphanage, both local to him in Cleveland, Ohio, and began what would become a lifelong practice of handing out coins to less fortunate churchgoers on Sunday mornings.

Rockefeller Sr. and his wife Laura impressed the importance of both frugality and generosity on their children from a young age. This ethic, combined with a lifelong struggle with mental health issues and a corresponding appreciation for the restorative power of nature, cleared a natural path to Rockefeller Jr.’s eventual role as a linchpin benefactor of the nascent national park system.

“Whenever he had these bouts—he had some pretty severe nervous breakdowns, even during his youth—he would retreat to one of the family’s estates near Cleveland, Ohio, to recuperate, to just spend time in nature, planting trees, chopping wood, cutting brush, just working around the estate doing manual labor, and that was his prescription for recovery,” said Kemp. “So at an early age, he made that connection between good mental health and time spent in the out of doors.”

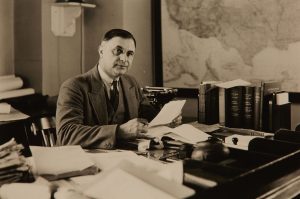

Rockefeller Jr. was 41 years old when a letter from Harvard President Charles W. Eliot changed the course of his life—and the future of national parks in America. Eliot sought money and support to preserve Mount Desert Island in Maine, where the Rockefellers loved to spend their summers, as public land. The effort culminated with the creation of Acadia National Park in 1916.

Rockefeller Jr., a shy, socially awkward man who Kemp describes as “kind of a nature nerd,” quickly recognized the importance of the national park effort and became a central figure in conservation projects across the country. All told, he donated the equivalent of $800 million in today’s dollars to expand the national park system. His steepest uphill battle came in the Tetons, where the park service convinced him to purchase 31,000 acres for the future Grand Teton National Park. When Wyoming officials fought the land’s transfer to the federal government, Rockefeller Jr. was forced to hold it for 23 years, paying property taxes the whole time.

“Those prerequisites of respecting the beauty of nature and mental health and the landscape architecture background and the pride in duty that he felt every minute of his life primed him to become that person who really accelerated development of the national parks,” Kemp said. “Nobody else would have fought 24 years for Jackson Hole [in the Tetons].”

Rockefeller Jr. wasn’t focused only on stewarding the landscape. He cared about the people as well. Kemp said he “melded with the National Park Service like a seasonal ranger. . . he just became one of them.” Rockefeller Jr. was continually impressed by how hard NPS employees worked and how dedicated they were to their mission. Many of them became his close friends, and he often used his wealth to help pay expenses like medical bills and college tuition.

“The ease in which a Rockefeller melded with these famous park service icons and granted their conservation wishes—almost like a genie coaxed from a magic lamp—is one of the most remarkable parts of the story,” Kemp wrote.

One of Rockefeller’s warmest such relationships was with Arno Cammerer, who was the park service’s associate director when Rockefeller Jr. made his donation. The gift came on the heels of a potentially catastrophic fundraising failure on the part of Major W. A. Welch, the man who had been tasked with the primary fundraising for the project.

The future of the Smokies hung in the balance, and Cammerer stepped into the gap, traveling to New York in hopes of discussing the project with his friend. But Rockefeller Jr. was an extremely busy man—their short meeting left no time to consider the Smokies, but Rockefeller Jr. invited Cammerer to make his pitch in a letter. Cammerer rose to the challenge, explaining the park’s potential to save priceless virgin forests, provide respite to millions of Americans unlikely to ever have the opportunity to visit the distant western parks, and “wipe out the greatest moonshine distilling section of Tennessee”—an attractive outcome for the teetotaling Rockefellers. After receiving the letter, Rockefeller Jr. donated an unheard-of amount of money to preserve a mountain wilderness he had never seen.

It’s hard to say what would have happened to the Smokies without Rockefeller Jr.’s help. Perhaps the land would have become a national forest. Perhaps it wouldn’t have been conserved at all.

“Without Rockefeller,” Kemp said, “the whole drive would have collapsed.”

Steve Kemp is the former interpretive products and services director for Smokies Life. He will present his new book An Exaltation of Parks: John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Crusade to Save America’s Wonderlands, at 6 p.m. Thursday, August 28, at the Anna Porter Public Library in Gatlinburg. The book is published by The University of Utah Press and widely available at bookstores and online retailers.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.