I was at least an hour and a half into my conversation with June Goforth when I joked that she hadn’t given me a chance to ask any questions. She paused a moment before laughing and said, “Oh, I didn’t know you had questions.”

I had sat down with Goforth to talk about Camp Margaret Townsend, a Girl Scout camp that was a summer home away from home for hundreds of girls between 1925 and 1959. Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont now occupies the site in Great Smoky Mountains National Park near Townsend.

Goforth, one of those people whom former campers recall with great fondness, had no shortage of memories to share. She started attending the camp as a child in “1943-ish,” working her way up to be a counselor-in-training and eventually a counselor. As a college student, Goforth was a swim instructor and “Director of the Waterfront.”

The camp that would come to mean so much to Goforth and countless others like her was founded through the efforts of Mabel Ijams, a Knoxville Girl Scout Council member and daughter of Little River Lumber Company President “Colonel” W. B. Townsend. Mabel fell in love with the site, convinced her father to donate it to the Girl Scouts, and named the camp for her mother, Margaret Townsend, who had died two years earlier.

The camp ran from late June through the middle of August, with many girls staying for as long as a month. They hiked, played games, rode horses, and made crafts but also had to haul wood, water, and supplies for cooking and cleaning. Goforth and others I interviewed also told of using pickaxes to cut trails and local timber to build platforms and other camp features.

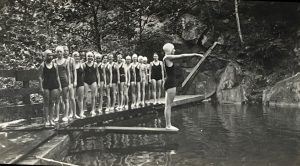

The “swimming pool,” a section of the Middle Prong of the Little River surrounded by great boulders up against a steep cliff, is a beloved memory for many former campers. A cement dam with a removable board allowed the river to flow freely when summer ended. A wooden platform forming a “crib” around the pool gave swimmers a diving board and a place to stand in the deep end.

As one of my interviewees, Carol Ware (née Goodwin), said, the water was “cold as whiz.” Still, many a girl learned to swim in those frigid waters. Margaret Weirich (née Mann), who attended camp for several years in the 1950s and credits Goforth with teaching her how to swim, would go on to participate in a synchronized swimming club during her college years at University of Tennessee.

“Forever after, the cold water of the Smoky Mountains has been imbedded in my fondest memories,” she said.

Not everyone, alas, learned how to swim. In a written account of his time working as a handyman at the camp, Ted Witt detailed how Goforth had once assured him that anyone could float. She instructed him to enter the water and float face-down, grasping his knees. Well, the poor young man sank like a stone. As he sputtered back to the surface, Goforth shrugged and said, “You don’t float.”

While feelings about the frigid swimming pool are mixed, most former campers fondly remember gathering around the campfire at night for songs and stories. Weirich recalls “wonderful summer nights” spent singing “completely a cappella, with harmony we newcomers picked up by just participating as we sat on the floor, with only Coleman lanterns for lighting.”

Most of the former campers and staff I spoke with remain in contact with lifelong friends they met at camp.

“The friendship aspect of Girl Scouting in general, and specifically in our camp, was very special,” said Elizabeth French. “We had no electricity, no plumbing, no telephones. We were out there just having the most wonderful time, in the most simple environment.”

The camp years live on as beloved memories in the women’s minds but also brought their share of harrowing experiences.

Anne Lacava (née Loftis) described an overnight camping excursion next to Laurel Lake in Townsend that was interrupted by heavy rains. The campers had pitched their tents on a hillside and were initially miserable because it was too wet to get a good fire going for s’mores. As the lake rose, the bottom set of tents began to float away, and the girls in those tents joined campers further up the hill. Then the middle set of tents was also lost, and the girls moved to higher ground once more. Lacava said no one was scared.

“All of us apparently spent the night until they did come and evacuate us eating Hershey’s bars and graham crackers and marshmallows, and that kind of takes the fear away when you know you’ve got enough of those to last you,” Lacava said.

Witt had dropped the campers off earlier in the evening and then, seeing that he wasn’t needed, left them to their adventure. Around midnight, Camp Director Judy Nickerson roused him, worried about the rain. As the two adults approached the campsite, the light from their headlights revealed “several drenched campers standing in water and mud.”

“The tent pegs had come loose, so no tent was left standing,” Witt told me. “Sleeping bags were on the verge of floating!”

He helped load the campers into the truck and got them back to camp to warm up, returning in the morning to gather the sodden gear.

Lacava remembers that rainy night mostly for the camaraderie she felt with the other girls. Later, as an adult, she realized how scared the staff must have been for the girls in their charge.

“If you think about it,” she mused, “the fact that they could maintain their fear and not feed it to us is another pretty neat thing; we were just clueless.”

Animal encounters could also inject moments of fright into camp life. Witt remembered hearing a noise in the camp as he prepared for bed one muggy August night and realized it was a bear. He put down his lantern, got out a powerful flashlight, and shined it right in the bear’s eyes. It growled, so Witt started clapping his hands. Joined by Margaret “Cookie” Cook, he chased the bear away from the sleeping campers. The next morning, several campers sheepishly relinquished contraband snacks they had been keeping in their units.

Other campers weren’t so willing to sacrifice their stash. Penny Cole and Lynn Crowell remembered one night when a mouse ran right across the face of one of their sleeping tentmates. They got scolded for having food in their tent, but rather than give it up, they decided to keep the kerosene lamp lit all night to prevent the mouse from coming back. Their counselor, Mary Stewart Neely, warned them they would use up their kerosene and wouldn’t get any more for the next night. They thought she was bluffing, but she wasn’t. The next night, they suffered through pitch-black darkness.

Camp Margaret Townsend closed in 1959 after the Girl Scouts’ lease with the National Park Service ran out. Everything that couldn’t be salvaged was bulldozed, and the old mess hall was burned to the ground. Many campers remember being devastated. Goforth said the closure was such a “painful experience” that she did not return to the place for years.

The Tanasi Girl Scout Council opened a new camp more than 60 miles away on the shores of Norris Lake. Though some campers did move on to Camp Tanasi, those who spoke with me said it was never the same. Jean Dysart and Marty Marsh summed up their feelings succinctly, agreeing that, “There never has been, and there never will be again, a camp like Camp Margaret Townsend.”

Camp Margaret Townsend alumnae and current Girl Scouts are invited to celebrate the camp’s legacy at a reunion Saturday, September 27, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., at the Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont. For more information and registration links, visit www.GirlScoutCSA.org.

This story was originally published in the spring 2025 issue of Smokies Life Journal, a twice-yearly magazine that is the primary benefit of joining for the 29,000-member Smokies Life, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting the scientific, historical, and interpretive activities of Great Smoky Mountains National Park by providing educational products and services such as this column. To read more stories like this while supporting Great Smoky Mountains National Park, visit SmokiesLife.org/Membership and become a Park Keeper.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.