Editor’s note: This piece is the first of a two-part series exploring plans to rebuild I-40 through the Pigeon River Gorge and the project’s implication for wildlife populations in the region.

When I-40 through the Pigeon River Gorge first opened in October 1968, it was hailed as a triumph of human accomplishment, the dawn of a new era for travel, tourism, and economic opportunity in newly linked Haywood County, North Carolina, and Cocke County, Tennessee. “Instead of going over or around mountains . . . man now goes through them,” proclaimed an advertisement in the special issue of the Waynesville Mountaineer celebrating the road’s grand opening.

But this “milestone to the genius of man” was more vulnerable than it first appeared, as proven by Hurricane Helene’s September 2024 onslaught. The raging Pigeon River undercut the steep slopes supporting the road, carrying away entire chunks of eastbound lanes in the worst-hit section, extending from the Tennessee–North Carolina line to NC mile marker 4.5. The road remained closed through March 1, 2025, reopening with 12 miles of single-lane travel in each direction.

Natural forces have caused plenty of closures during the road’s nearly 60 years of existence—rockslides from the sheer cliffs rising from the north side are the most common reason—but Helene was unique in the scale of the damage it caused. Rebuilding a road that would provide safety to travelers and durability in the face of future natural disasters presented the NC Department of Transportation with a monumental task.

It also stands out as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to the Safe Passage coalition, a group that has been working since 2017 to reduce wildlife–vehicle collisions in the gorge. The project has the potential to be an enormous win for wildlife connectivity in the gorge—or a huge loss. The cost is currently estimated at $2 billion, and engineers hope the rebuilt road will last for as long as 100 years after its completion in late 2028 or early 2029, meaning it could remain in place for generations.

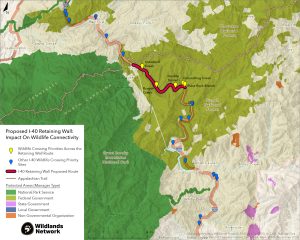

In the first project of its kind in North Carolina, NCDOT plans to use roller-compacted concrete to build an enormous wall—20–30 feet tall and averaging 30 feet thick—stabilizing the slope between the road and the river and protecting it from erosion. Those plans, nearing their final form, have Safe Passage members alarmed.

“It would be a huge loss for the Safe Passage coalition and everything we’ve been trying to accomplish,” said Ron Sutherland, chief scientist for Wildlands Network, a Safe Passage coalition member.

The Pigeon River Gorge has been the focus of Safe Passage’s work since its inception, with the I-40 corridor representing a unique risk to wildlife connectivity and biodiversity. The road section, which in 2023, prior to Helene, saw an average of 26,500 cars each day, divides a rugged mountain landscape that includes a narrow band of national forest acreage, about half of which falls within the rebuild area. This forest connects a swath of federal land stretching hundreds of miles from northern Georgia into northern Virginia and southern West Virginia. Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most biodiverse site in the National Park System, lies just to the south. Ensuring animals can move safely from one side of the highway to the other is crucial to ensuring genetic health and resilience in the face of hardships like food shortages, habitat loss, or changes in climate.

“It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this corridor from the Great Smoky Mountains northeastward for wildlife and biodiversity,” Sutherland said. “It’s kind of the major pathway for wildlife and climate migration and everything else in the whole region.”

NCDOT has been a partner in that priority, collaborating with Safe Passage and, where possible, integrating the group’s recommendations into its designs. Many of these recommendations came from a 2022 report that was based on a three-year study focused on bear, deer, and elk movements. Funded by Safe Passage, the study was conducted by wildlife biologists with Wildlands Network and National Parks Conservation Association to identify the gorge’s wildlife crossing hotspots and make recommendations to help support habitat connectivity and improve transportation safety.

While the study was still underway, Safe Passage used the emerging data to deliver recommendations for five bridges slated for replacement in the gorge. As a result, the Harmon Den bridge at Exit 7, completed in 2023, features wildlife-friendly dirt paths underneath as well as fencing and cattle guards to prevent animals from wandering onto the highway. Four additional bridge projects in the area are now either complete or nearly so. All include some type of research-driven wildlife crossing feature, and all survived Helene. Meanwhile, NCDOT’s growing relationship with Safe Passage helped inspire the design of a new overpass for wildlife and Appalachian Trail hikers, currently being installed on NC 143 at Stecoah Gap near Robbinsville, North Carolina.

“These are all really positive things,” said Jeff Hunter, NPCA’s Southern Appalachian director. “Unfortunately, Helene set us back.”

Before the hurricane, the decimated section of I-40 contained one of the most important wildlife crossings in the entire gorge: the double tunnel, where all four lanes of the highway go underground, leaving a natural, wooded area on top that creates an earthen bridge for wildlife. But Helene carried away the land that had connected this bridge to the river, leaving animals to navigate an impassable 90-degree drop-off.

“None of us, I don’t think, could have envisioned we would have lost that crossing,” Hunter said.

Pre-Helene, the big push in this area had been at nearby Groundhog Creek, where Safe Passage hoped to carry out a culvert improvement project that would greatly benefit wildlife connectivity. Culverts don’t just move water; wildlife use them too. The 2022 report had found that the trio of culverts moving Groundhog Creek under I-40 had some of the highest levels of wildlife activity in the entire gorge, with cameras recording species ranging from bobcat to bear. To make the crossing even more effective, researchers recommended replacing the three culverts with one big pipe able to accommodate even large animals like antlered deer and elk, with additional modifications to make it more useful to a wide range of species. The report also recommended enlarging the culvert at Snowbird Creek, also located within the rebuild corridor; though topography prevented researchers from placing a camera there, collision data indicated the creek crossing was a hotspot for wildlife activity.

But Helene changed the equation, creating an urgent situation that required immediate action on I-40—and, simultaneously, everywhere else in Western North Carolina. With reliable thoroughfares obliterated and entire communities cut off from the outside world, NCDOT faced a seemingly impossible task.

“When it comes to emergency repair projects like this, it’s of course an all-hands-on-deck kind of approach,” said John Jamison, head of NCDOT’s Environmental Policy Unit. “Not only is it a rush to figure out what needs to be repaired and how to repair it and actually do the repairs, but there’s a lot that goes into the conversation about how does it get funded.”

Normally, major road projects go through a years-long process of planning, design, and community engagement. Before the first shovel hits the ground, NCDOT and local stakeholders engage in extensive conversations about the proposed plan, alternative approaches, and opportunities to fund enhancements.

But Helene recovery projects are a form of emergency response and don’t follow that same process. Nor are they primarily tied to state funding. Instead, the Federal Highway Administration’s Emergency Relief Program covers up to 90 percent of the cost—provided plans meet the agency’s criteria. For NCDOT, that financial support was critical. Hurricane recovery projects across the state are expected to total about $5.8 billion, an enormous expenditure considering that in fiscal year 2023–2024, funding for construction projects statewide came in at $3.5 billion.

“We’re essentially funding a big loan on these projects,” Jamison said.

As the floodwaters receded, Safe Passage members had high hopes that the tragedy could hold a silver lining for wildlife. With I-40 closed and major roadwork inevitable, why not add culvert enlargements or even road section reroutes into the recovery plan? Could the highway perhaps be reimagined as a viaduct, supported by pylons that would allow both water and wildlife to move freely underneath?

But federal reimbursement rules—combined with a desire to see the road fully reopen as quickly as possible—have dashed those hopes. FHWA emergency funds cover only road “replacements,” not road “improvements.” Though the eastbound lanes were severely damaged, westbound lanes and culverts remained intact, so the kinds of projects on Safe Passage’s wish list would have fallen under the “improvements” category, leaving NC taxpayers on the hook for the entire cost.

“That funding uncertainty made it fairly straightforward for us to stick to the existing roadway,” Jamison said.

Part 2 of this series will take a closer look at the planned rebuild, opportunities to benefit wildlife passage, and the factors influencing these decisions. Smokies Life is a member of the Safe Passage coalition.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.