Editor’s note: This is the third installment of Anne Bridges’ three-part series on a Blount County outlaw known as Hut Amerine and his illegal moonshining enterprise in the Great Smoky Mountains prior to the creation of the national park. Click here for part one and here for part two.

Hut Amerine did not wait for a court to decide his fate. According to a November article in the Nashville Daily American, jailers discovered that Amerine and several other prisoners were attempting to escape from the Knoxville jail. They were transferred to the “dungeon,” a location in the basement thought to be escape-proof.

The prisoners soon began new escape plans. They dug up the flooring around a sewer pipe that passed from the cell above into the stone foundation. The determined men removed the brick wall surrounding the pipe. All together, they excavated a “two-horse wagon load of clay and other substances,” creating an opening under the wall which allowed for their escape. The jailors discovered that the prisoners were missing soon after they had made their bid for freedom. Amerine broke the ropes tethering a skiff and rowed across the Tennessee River, headed back to his home.

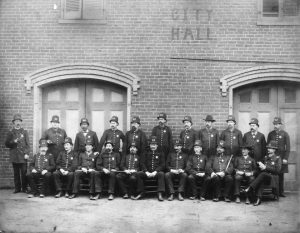

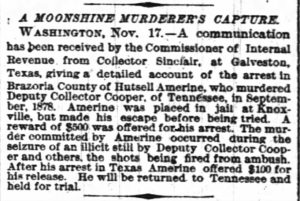

Amerine hid in Blount County for some time and then headed with his family to Brazos County, Texas, where his brother lived. In 1880, federal agents and relatives of John Cooper received word of Amerine’s location. Federal marshal W. T. Clayton tracked him down and arrested him as he worked on his farm. With his prisoner in handcuffs and frequently chained to his seat, Clayton headed back to Knoxville with Amerine via rail.

As the train sped along at least 35 miles per hour, just south of Chattanooga, Amerine asked that his chains be removed to permit him to go to the bathroom. The guard neglected to chain him to his seat upon his return, assuming that the high rate of speed that the train was traveling would deter any chance of escape. According to the account in the Nashville Daily American, “Something in the car attracted Clayton’s attention, and light as the wind, nimble as a cat, determined as a man who sees a hangman’s rope dangling before him, Amerine stealthily rose from the seat approached the door, in an instant was on the platform.” He jumped off the moving train.

As the train sped along at least 35 miles per hour, just south of Chattanooga, Amerine asked that his chains be removed to permit him to go to the bathroom. The guard neglected to chain him to his seat upon his return, assuming that the high rate of speed that the train was traveling would deter any chance of escape. According to the account in the Nashville Daily American, “Something in the car attracted Clayton’s attention, and light as the wind, nimble as a cat, determined as a man who sees a hangman’s rope dangling before him, Amerine stealthily rose from the seat approached the door, in an instant was on the platform.” He jumped off the moving train.

Clayton proceeded to Chattanooga and enlisted the help of a local detective. They went to the scene of the escape, where they determined from marks on the ground that Amerine must have tumbled and rolled into a ditch. He was tracked for some distance, and then all traces of him disappeared. According to an 1899 report in the Knoxville Sentinel, he convinced an old man to break his handcuff. In an interesting detail, Amerine had with him seven dollars and a “small pen-knife.”

In the meantime, Fletcher Emmett was tried in state court and sentenced to labor in the Coal Creek mines for resisting arrest during the first raid on the Amerine still. Adam Wilson was tried for the murder of Cooper and was sentenced to 22 years in federal prison in Albany, New York. Subsequently, Emmett had an accident in the mines, breaking his leg. He was then tried in federal court and sentenced to 22 years minus time served in the mines. He was also sent to the federal prison in Albany. Later both men were pardoned by President Chester Arthur.

Amerine made his way to Oklahoma. He died in 1891 at the age of 53 and was buried in a Tulsa, Oklahoma, cemetery. The Knoxville Journal reported his death: “With all his faults he had good qualities. He was by nature generous, and he was true to his friends. Many will hear of the death of Hut Amerine, as he was generally known, with feelings of regret.” Amerine never came back to Tennessee and never stood trial for the murder of John Cooper.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.