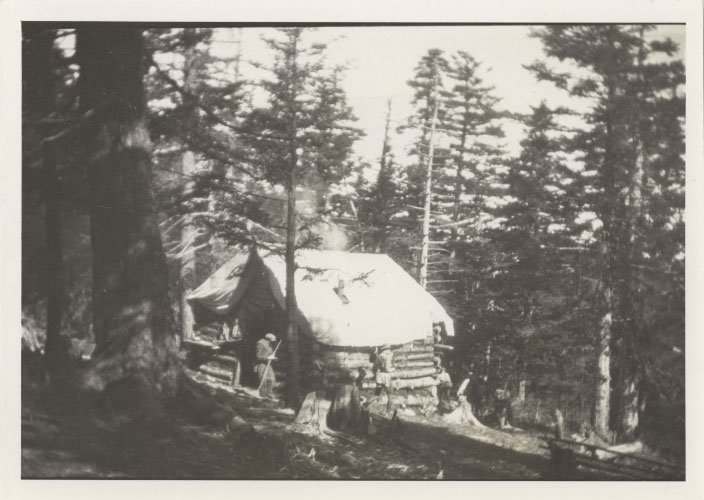

In late fall of 1925, Paul Adams was astonished to see a visitor walk into his camp on Mount Le Conte. Adams, a young man of 25, had been hired by the Knoxville-based Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association to oversee visitor facilities on this most iconic of Smoky peaks. At this point, the mountain was owned by Champion Paper Company but was increasingly of interest to hikers, hunters, botanists, birders, and others attracted by the possible formation of the national park. Adams was to make guests comfortable or as comfortable as he could in the rudimentary structures he was able to build as part of his camp.

It was not unusual for Adams to have guests since accommodating visitors and protecting the mountain from fire and other damage was his job. But this particular guest was not like other people who had made the climb from Gatlinburg up Rainbow Falls Trail. Adams described the visitor as wearing “a light grey suit, low-cut shoes, spats, white shirt, bow tie and a derby hat”—not the usual hiking attire of the time. He was carrying two cameras but no pack or extra supplies. The visitor was Frank Bohn, columnist for the New York Times. He asked Adams for directions to the hotel on the mountain summit, and Adams responded that he had arrived. Bohn reached into his pocket and pulled out a letter from Colonel David Chapman requesting that Adams assist Bohn in gathering information and taking photographs of Smoky Mountain flora and fauna.

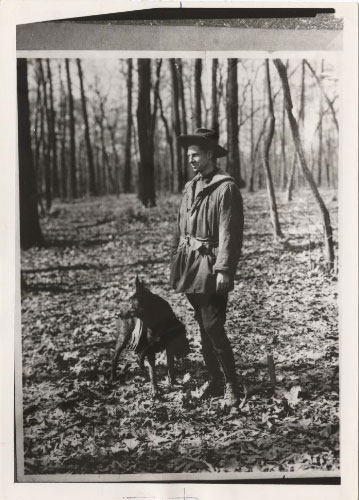

Colonel Chapman was vice-chair of the Conservation Association, whose members were heavily involved in promoting a national park in the Smokies. It was Chapman who hired Adams as custodian of Mount Le Conte. Of course, Adams took any direction from Champion seriously. He found more appropriate clothing for Bohn and proceeded to prepare lunch for his guest. After lunch, the two men, accompanied by Adams’s German shepherd, Smoky Jack, hiked to Myrtle Point so Bohn could take photographs and see the view, which, according to Adams, Bohn declared to be “the most beautiful he had seen in Eastern North America.”

By evening, the wind had started to pick up, but, despite the fierce gusts, Adams had to make fire patrol. Bohn accompanied him. First, they went to Myrtle Point where the wind was so strong it pushed Adams and the reporter into the myrtle and rhododendron, causing them to lose footing a time or two. Adams was used to this rough weather, but Bohn was not. As they followed the trail around the edge of Cliff Top, Adams shouted to Bohn that if he started to fall, to grab something to his right. Once Bohn had fallen a few times, he started crawling on his hands and knees along the trail. After Adams climbed the fire tower and made his observations, Bohn asked if there wasn’t another way back to camp. Adams observed that Bohn was clearly frightened. They took an older trail back to camp with the wind still roaring and the echoing sounds of trees snapping. The next morning, Adams made a quick breakfast and accompanied Bohn back down the mountain to avoid the rain he knew was coming.

Back in New York, Bohn wrote an article about his trip to the Smokies, which appeared in the New York Times on January 25, 1926, with the title “A New National Park.” Like many pieces written about the Smokies during this period, much of the article was a glowing review of the mountains, calling them “one of the half dozen most remarkable natural scenes in our country.” Unfortunately, none of the photographs that Bohn took on Le Conte accompany the article. But, in light of Adams’s account, it is his description of his trip to Mount Le Conte that is most interesting.

He calls his hike up Le Conte “a rough climb” and calls for a “fine automobile road” along the summit. Then, he describes Adams: “At the very top of Le Conte there is a boy living alone in a cabin made of slabs. The writer saw in the cabin a single volume, namely Thoreau’s ‘Walden.’ It had been read and reread and marked over and over again.” Bohn’s romantic view of Adams, who was hardly a boy at 25, omits all the terror of windy Myrtle Point and the fire patrol trip. Instead, it casts Adams—not as a practical and capable guide—but as an idealistic Thoreau of the South for urban readers eager to indulge in the possibilities hidden within the mysterious and remote mountains.

Adams, for his part, recorded the episode more plainly in his personal diary, a meticulous ledger of events and observations that he began as a teenager and maintained for the rest of his life.

The differences between these accounts from two very different men, each with his own area of expertise and motivations, make for an amusing anecdote. But it’s also an anecdote that hints at a dynamic that was quite common at the time as newcomers explored the Smokies and, in the process, applied their own assumptions, interests, and agendas on the land and the locals they found there.

While the Smokies have certainly changed since these two crossed paths atop Mount Le Conte nearly a hundred years ago, it’s safe to say some things have not. There are always two sides to any story.

For more on Paul Adams’s time on Mount Le Conte, see: Adams, Paul J. Mount Le Conte. Edited and introduced by Ken Wise and Anne Bridges. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2016.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.