Growing up in Swain County, North Carolina, Nathan Dee Greene ate a lot of apples. The family had several trees of their own, but every fall, they bought bushels from the nearby orchard on Laurel Branch, across the Tuckasegee River from Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

“My mother would go all day, and she’d pick up the apples in a tote bag, and after school, I would go over and get them and sled them home,” said Greene in an archived interview. Now deceased, he was nearly 86 when he spoke with Nathan Somers in 2004 for the conversation now catalogued as part of Western Carolina University’s Oral Histories of Western North Carolina project. “At that time the roads in this community, there was only sled roads; it was very small and very narrow and therefore it wasn’t big enough for a wagon. And you used sleds back then all the time.”

Whether fresh from the tree, sun-dried, sulfur-treated, or preserved as apple butter, cider, brandy, or vinegar, the apple was a beloved staple in the days before refrigeration and global distribution networks. The versatile fruit thrived in the cool mountain climate, playing an important role in farms and communities throughout the Smoky Mountain region.

“The real benefit to those farm families having apples is that they last for a long time in root cellars,” said Jesse Webster, a forester with Great Smoky Mountains National Park. “Cool, rock-sided apple barns could house those apples throughout the fall, throughout the winter, into the spring of the next year.”

The rocky remains of these structures are still scattered throughout the park, along with aged apple trees still clinging to life in the shade of the surrounding forest. Since 2019, Webster and his colleagues have been engaged in a project seeking to save these living remnants of the park’s cultural heritage.

“We’re protecting what we have on the landscape, because it helps connect the story that we’re telling,” Webster said. “It’s that link to the past.”

According to idiom, nothing is as American as apple pie. But the apple, like the forebears of most Americans, is an immigrant, originating half a world away in Kazakhstan. The wild crabapples that are the ancestors of all modern apple trees were first cultivated 8,000 years ago. Since then, they have traveled the world, with thousands of varieties bred for attributes like crispness, sweetness, and suitability for baking or long storage. Apples first arrived in the Americas sometime in the 1500s, with Native peoples as well as European settlers further adapting them to their own purposes.

“It’s pretty fascinating if you think about how apple trees have changed over time,” said Interpretive Park Ranger Michael Smith, who manages the Mountain Farm Museum adjacent to Oconaluftee Visitor Center and the eight apple trees in its orchard.

The oldest apple trees known to exist within the National Park Service are on The Purchase, an area of the Smokies in Haywood County, North Carolina, that was added to the park in the 1990s. For about a century, this mountain was home to the Ferguson family, who cleared the land for livestock and agriculture—including apple trees, which thrived at the 5,000-foot elevation.

Today, more than 30 apple trees persist on The Purchase, and though they’re now more than 125 years old and have gone decades without human care, they’re still healthy. To keep them that way, in 2022 Webster and his crew cleared out nearby trees that were shading out the apples and began to prune and mow around the neglected fruit trees. Now, said Webster, “they’re really looking great.”

The next step was to identify the trees. Historically, at least 16,000 types of apples were grown in the United States, but as fewer people kept orchards and suitability for storage and global transport networks grew in importance, many cultivars became either extinct or extremely rare. Cameron Peace, a professor of tree fruit genetics at Washington State University, estimated that fewer than half of these historic varieties still exist. Many of the names Greene mentioned in his interview—Hog Sweet, Winter John, Sheep’s Nose, Rusty Colt, Yellow Pippin, and Nonesuch—are unfamiliar to today’s apple eaters.

Identifying rare apple trees was once an arcane and time-intensive art, but the advent of rapid and inexpensive DNA testing has made it much easier. The park partnered with Peace, who runs a fruit tree identification project called MyFruitTree, to test six trees at The Purchase.

Results showed that one of the trees was a Magnum Bonum, an apple common in the South through the 1930s. Nurseries dubbed it “the king of all fall apples,” according to the Southern Heritage Apple Orchard’s Apple Index; the fruit had white flesh sometimes stained red near the skin, and in taste it was “tender, juicy, fine-grained, aromatic, and mildly subacid.”

Most apple trees are actually a combination of two separate trees—the root stock, which determines how tall the tree will grow, and the scion, which determines what kind of fruit the tree will produce. Instead of using seeds, orchardists typically graft a scion of their desired cultivar onto a root stock, ensuring that the exact genetics of the desired cultivar are preserved.

DNA tests showed that the other five trees were the offspring of two different types of apples, indicating that, rather than growing from carefully grafted seedlings, they had likely been incidental plantings, sprouting up from a fallen apple left decaying on the ground. Identifying the trees’ parents could uncover the likely identities of older trees that have long since vanished from the Ferguson orchard.

“There are millions of trees out there, and we aren’t going to value them if we don’t know much about them,” said Peace. “If you know the name, it connects you with all the other stories, all the people who have ever grown it and enjoyed it and talked about it and written about it. It brings you into the big story. Otherwise, it’s just an orphan out there.”

Though local lore held that most of the Fergusons’ trees had been Limbertwigs, only one of the five trees tested had a type of Limbertwig as one of its parents. Another was the offspring of a Tolman Sweet, and two more a Ben Davis. Two of the trees had the same mystery cultivar as a parent. The trees’ DNA matched a sample held by the Temperate Orchard Conservancy in Oregon labeled as “Pittsburg,” but Peace has not yet been able to confirm whether the Pittsburg label itself is correct. Three more parents remain a mystery.

“Some of these trees we’re finding at Purchase Knob might be rediscovered varieties,” Webster said.

The Purchase is not the only place in the park with old apple trees. Webster is working to find and identify additional trees, now awaiting results on 15 specimens that have been sampled at Cades Cove, Cataloochee, Smokemont, and a high-elevation site along Kuwohi Road. Webster expects to finish assessing the park’s apple trees by spring 2026.

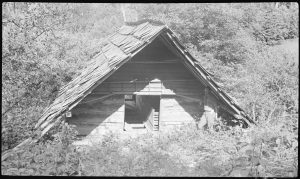

Though he anticipates finding plenty more apple trees that have persisted, overlooked, in previously inhabited areas of the park, there’s already an easy way for visitors to experience the Smokies’ apple harvest history. At the Mountain Farm Museum next to Oconaluftee Visitor Center, eight apple trees grow inside a high fence—erected in 2015 to protect the trees from elk—next to an apple barn that once stood on a farm in Little Cataloochee.

“For us here in the park, we’re not intensive like you’d see on commercial orchards,” Smith said. “We don’t treat trees or spray trees for insects. We don’t use any fungicide. We let them be more natural, a little less input. We don’t fertilize.”

Every year, Smith and his colleagues prune the trees and assess their condition. Most of the easy-to-reach apples end up being picked by visitors, but any that remain are either fed to the farm’s pigs and chickens or used as educational tools at the annual Mountain Life Festival, held at the farm each September.

“You have to decide what the purpose and the goal for your orchard is,” Smith said. “For us, it’s to have trees and a small orchard and produce some apples, but also to talk about why those apples were important to people.”

In every apple is a taste of history—and a mouthful of possibilities. Old apple trees like those found in the Smokies offer the potential not only to resurrect historic varieties, but to create new ones.

“Anyone can cross anything with anything,” Peace said. “The more people are doing that, the more we are recreating that diversity that used to exist. A lot of that crossing has already been done by nature itself, and so you can just go out and find these old trees, and if they’ve got some really great attributes, then bang—there’s a potential new cultivar.”

Do you have an old apple tree on your property? Learn how to get its DNA tested by MyFruitTree.org.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Great Smokies Welcome Center is located on U.S. 321 in Townsend, TN, 2 miles from the west entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Visitors can get information about things to see and do in and around the national park and shop from a wide selection of books, gifts, and other Smokies merchandise. Daily, weekly, and annual parking tags for the national park are also available.